Manhattan Beach’s Terry McDermott pens hardball inquiry “Off Speed”

The cover of “Off Speed,” McDermott’s newly released book. Photo courtesy Pantheon Books

In August 1982, Major League Baseball fined pitcher Gaylord Perry $250 and suspended him for 10 days. The penalties originated from an umpire’s ruling that Perry, then pitching for the Seattle Mariners, had doctored two of his pitches in a game against the Boston Red Sox.

News of the suspension was notable in part because Perry was one of the most successful pitchers of the era. The “Ancient Mariner” was slogging through his 21st season, and was just months removed from the high of his 300th win. But the accusations of pitch doctoring really took hold for another reason: Perry had previously admitted to that very thing.

Written at the height of his career, in 1974, Perry’s “Me and the Spitter: An Autobiographical Confession,” detailed his early use of the spitball, a pitch whose grab-bag material history began with saliva and came to include Vaseline, shoe polish, and tobacco. Properly thrown, the foreign substance alters the path of the ball, making it harder for a hitter to track. The spitter caught on at the turn of the century, becoming wildly popular before Major League Baseball declared it an illegal pitch in 1920.

Perry appealed the umpire’s decision to the commissioner’s office, claiming that the pitches in question were just well-thrown fork balls. The era recounted in his autobiography was a long time ago, Perry insisted; he had long since abandoned the spitter. Hitters — and umpires — were skeptical, though, that Perry had ever stopped, noting the hurler’s habit of touching his cap and various parts of his uniform before winding up.

Perry lost, but made a revealing argument in the process. Though he no longer relied on the spitter, he did rely on hitters believing he still used the pitch.

“It’s part of my game plan,” Perry told The New York Times as the appeal was pending. “I always leave a little evidence to make people believe I might be doing something.”

Terry McDermott reads from “Off Speed: Pitching and the Art of Deception” at 7 p.m. May 16 at Pages.

Perry is one of the many conjurers to pass through the pages of Terry McDermott’s wonderful new book “Off Speed: Baseball, Pitching and the Art of Deception.” McDermott, a Manhattan Beach resident and longtime journalist, digs in to the ways in which baseball, and pitching in particular, relies not just on outmaneuvering or overpowering opponents, but on fooling them. (Full disclosure: McDermott is the brother of Easy Reader editor Mark McDermott.) He will do a reading from “Off Speed” at Pages bookstore on Tuesday evening.

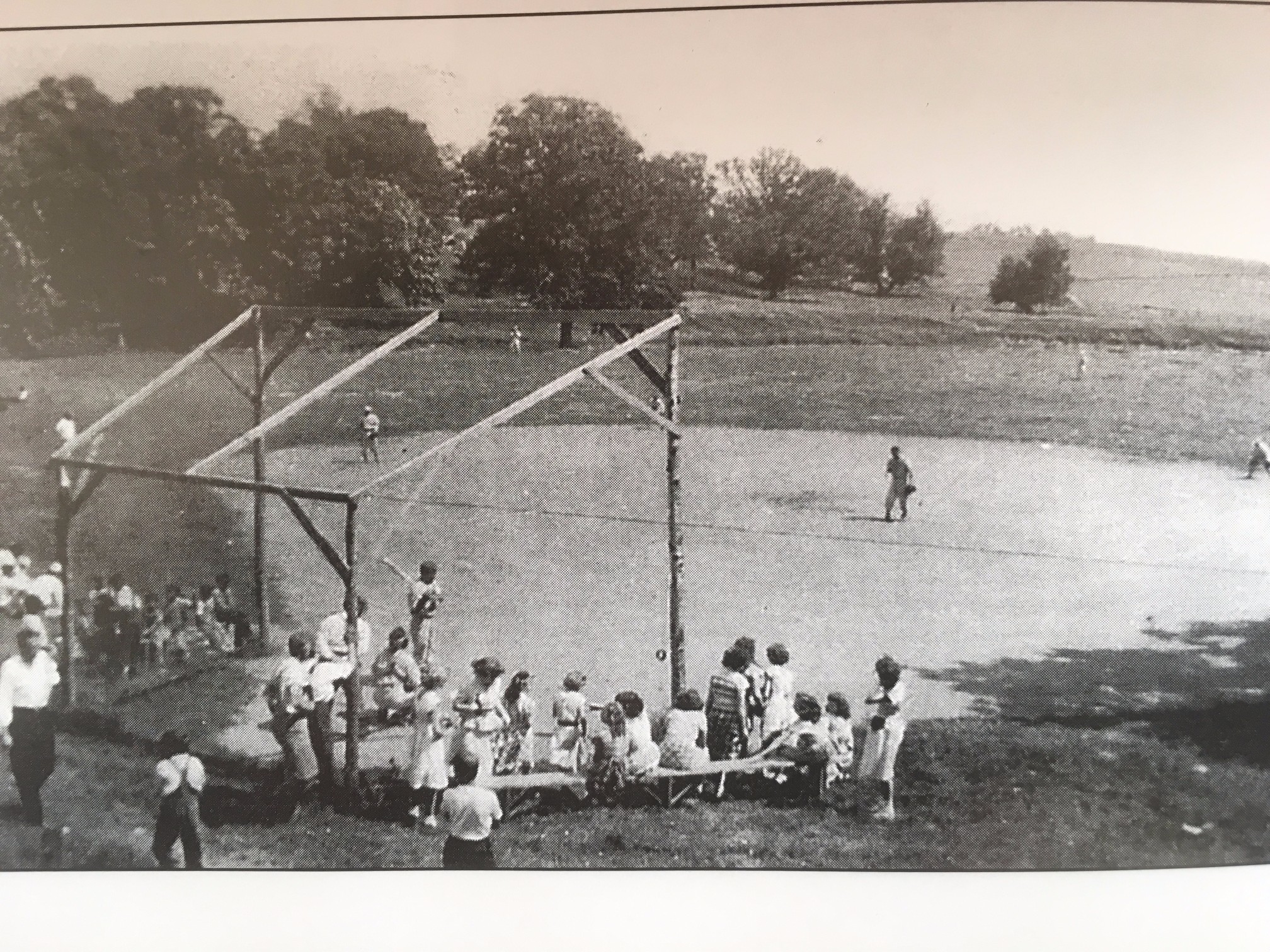

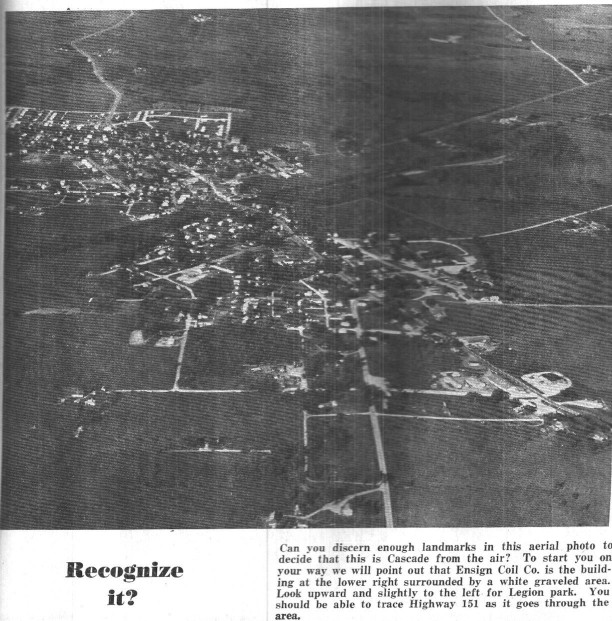

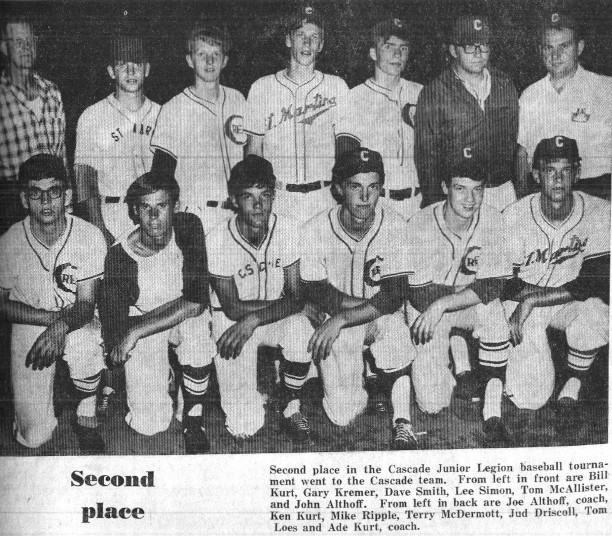

The differences between baseball and other sports have been picked apart by everybody from George Will to George Carlin, and trickery is a common concern. What McDermott brings to the topic is sensitivity: perceptive analysis, but also a levity that comes from connection the game. Like a baseball itself, “Off Speed” is composed of multiple layers. It is structured around an inning-by-inning analysis of a 2012 perfect game thrown by Mariners pitcher “King” Félix Hernández. Each of the nine chapters focuses on a particular type of pitch, its mechanics and its origins. And each chapter contains some of McDermott’s personal history with baseball, much of it focused on his growing up in Cascade, a baseball-mad Iowa town 15 minutes from the “Field of Dreams” cornfield.

The halcyon descriptions of growing up exist somewhat uneasily alongside a biographical tangent that runs sharply away from cornfields, and toward cosmopolitan cities and newspapers. McDermott is a former national reporter for the Los Angeles Times, and the author of definitive books about terrorism and the science of memory. But the subject of this book, and the place of baseball in his writing, is not so a dramatic a departure as it initially appears. (A former colleague once told McDermott that everything he wrote was about “baseball, my father and belief.”)

“I have always been interested in why I left there so soon. That’s been a question that puzzled me for a long time. And thinking about what I retained from there, baseball is one of the few things,” McDermott said in an interview.

Shaping the pitch

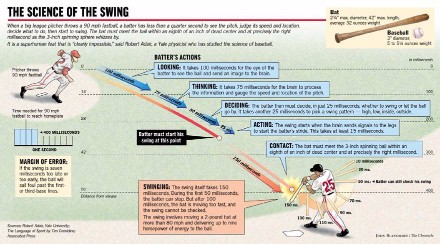

“A lot of guys don’t really learn how to pitch until they hurt their arm,” says longtime pitching coach Bob McClure in an interview cited by McDermott. An injury to a pitcher, McClure reasons, is a teaching moment. When forced to rely on something other than muscling the ball across the plate, mere throwing ends and pitching begins.But where, exactly, does it lead? What informs a pitcher, alone with the ball and his thoughts, 60 feet, 6 inches from home?

There are the Official Rules of Major League Baseball, which, as of 2016, run to 160 pages, much of it dense legalese. As McDermott relates, these rules are themselves the result of significant historical evolution. Far more than just reactions to absurdities that creep into the game — and if you stop and think, it is absurd that the governing body of a sport felt the need to formally clarify that slathering the game ball with spent Skoal is inappropriate — rule changes are attempts to make the national pastime better reflect our aspirations for it. And they are typically aimed at tweaking the balance between hitters and pitchers — at making sure batters get fooled, but not too often. The prohibition of the spitball sounded the end of the low-scoring “deadball era,” and heralded the rise of home run titans like Babe Ruth; Bob Gibson’s 1968 season, in which he notched an ERA of 1.12, was so dominant that it prompted a six-inch lowering of the pitcher’s mound.

There is strategy, which, as evidenced by Perry’s comments, can involve a kind of Prisoner’s Dilemma of guessing at what is inside a player’s head. McDermott cites two widely accepted maxims — strike one is the most important pitch you can throw, because batters perform worse when behind; establish the fastball in order to differentiate from breaking balls — that lead almost syllogistically to the importance of deploying fastballs early in at-bats to gain an advantage over the hitter. The stratagem, though, is hardly a secret. And, together with the fact that fastballs are the least deceptive pitch in a hitter’s arsenal, this leads to a rather ridiculous scenario for the pitcher. “To get to his really dynamite off-speed stuff,” McDermott writes, “he has to throw his most hittable pitches exactly when hitters most expect them.” The odd formality of this arrangement resembles nothing so much as the stilted ceremony attached to dueling, mortal enemies drawing weapons from plush cases and counting paces viva voce.

And, last but hardly least, is something that could be called mythology: ingrained practices that persist regardless, or even in spite of, strategy. Baseball players are notoriously superstitious, and many of these folkways likely have little impact on the game. (Wade Boggs, in addition to his famous pregame chicken, supposedly fielded exactly 117 ground balls in every warmup.) But others have real influence. McDermott cites the case of Jamie Moyer, who managed to stick around longer than almost any other player in major league history despite throwing with an embarrassing lack of velocity. Even more embarrassing, though, was the prospect of striking out on a Moyer fastball: What McDermott describes as pervasive “masculine vanity” made hitters so eager to crush Moyer’s pitching that they often whiffed on his changeups. Moyer ultimately recorded 2,441 strikeouts. “I would never have had a career if it wasn’t for the pride of major league hitters,” Moyer says.

It is this last category that is of most interest to McDermott. Mythology is what makes McDermott’s experience with playing and fandom relevant to a book about deception: whether playing in Safeco field or against a barn-door backstop, pitchers and hitters share in a tradition older and deeper than any player or pitch.

In one of the book’s most affecting passages, McDermott recalls his time as head ballboy for the Reds, Cascade’s local semipro team, during an exhibition game against a barnstorming team. The opposing pitcher was none other than Satchel Paige, the legendary Negro League player and “one of the two or three best pitchers who ever lived.” Paige, then 56, arrives for the game looking “skinnier than a cornstalk, with more wrinkles than a roadmap.” He pitches through a power outage that leaves half the field in darkness. And when the 10-year-old McDermott returns a foul ball, cleaned and dried of dew, the great pitcher pulls him aside. “He said, if it was all the same to me, he didn’t want to see any more clean balls the rest of the night. Let’s have some fun, he said, and winked.” The lure of the spitball endures.

Safe at home

Baseball has a longer history in the United States than any other of the three major sports. And far more of it has unfolded on something other than a television, which put fewer constraints on the space it occupied in the public imagination. Fittingly, it is a radio broadcast, streaming into his car on a lonesome highway, that reignites McDermott’s passion for the sport after years away from Cascade.

The idea for “Off Speed” bounced around in his head for years. When he first began in earnest, McDermottt had planned to structure it around in-depth interviews with a pitcher, breaking down a game pitch by pitch. He reached out to some two dozen pitchers, including both Moyer and Hernández. All ultimately declined.

“The most common response was that they didn’t want to give away secrets. You’ve got to be kidding me, right? Everybody in the universe who wants to know what you throw, they know what you throw: on what count, in what inning, on dry days, on wet days–it’s all there, the data exists,” McDermott said.

McDermott is correct, and his point reflects a fundamental shift that has occurred over the last two decades in baseball: the rise of sabermetrics, the empirical analysis of baseball statistics. Pioneered by historian and amateur statistician Bill James, sabermetrics has revolutionized the sport, and data of the sort McDermott described are now widely available on the Internet.

The clash between “stat geeks” and “traditionalists,” McDermott said, has been overhyped by writers like Michael Lewis, whose “Moneyball” documented the success of the small-market Oakland A’s. But he concedes that even if general managers have embraced data, many players have not. Hernández, for example, makes little use of the information the Mariners staff offer him. At one point he insists that his sinker is his best pitch; McDermott reveals on the same page that it is, statistically, his worst.

And yet Hernández remains among the most successful pitchers in baseball. How to explain the continued importance of feeling, of instinct and mystique, in an age riven by data and determinism?

The same year that “Me and the Spitter” was published, Orson Welles released “F for Fake,” his film essay on deception and authenticity in the art world. Welles relates the story that a friend of Pablo Picasso once presented the painter what the friend said was a genuine Picasso, only to have the master pronounce it a fake. The same friend showed him a different painting from another source, which Picasso also declared a fake. A third painting from yet another source was yet again, Picasso insisted, fake.

“But Pablo,” said the friend, “I watched you paint that with my own eyes.”

“Aha,” said Picasso. “I can paint false Picassos as well as anybody.”

Somewhere out there, Gaylord Perry is smiling.

Terry McDermott will do a reading from “Off Speed” at {pages: a bookstore} at 904 Manhattan on Tuesday May 16 at 7 p.m.

[Not a valid template]