Dora Maar, we hardly knew you!

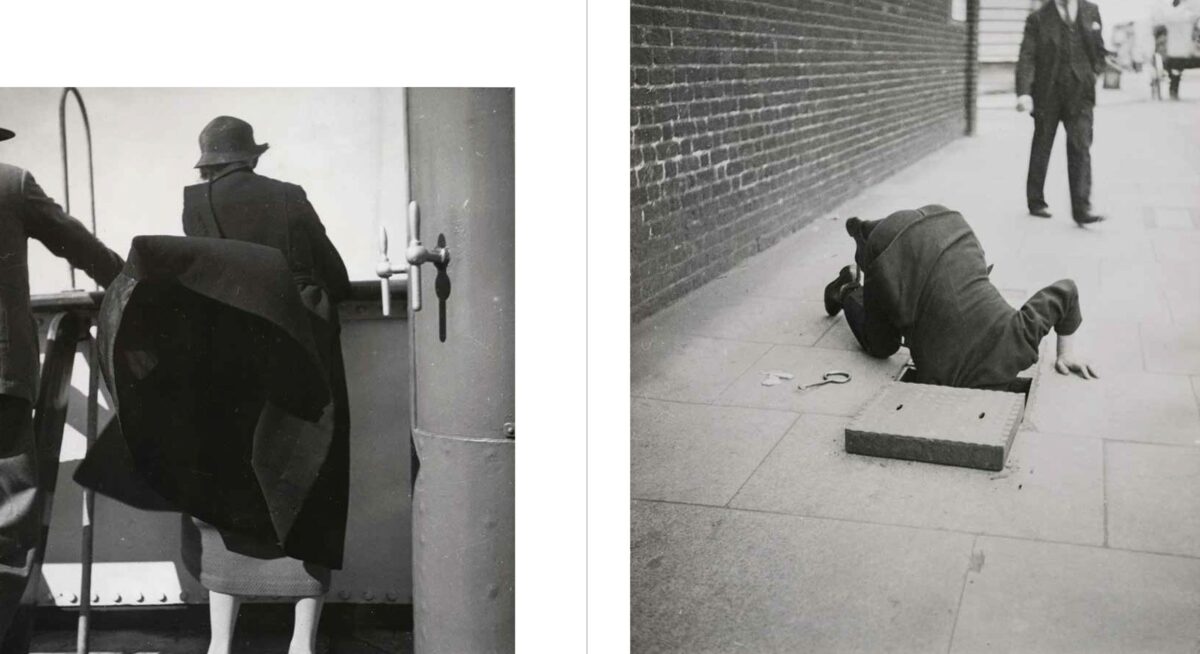

Pages 92 and 93 of “Dora Maar,” with “Untitled” (ca.1930) on the left and “Untitled (Man looking inside a sidewalk inspection door, London)” (1934) on the right

Dora Maar, Surrealist painter and photographer

Originally I might have titled this piece “No longer a footnote,” but the scheduled exhibition of Dora Maar’s photography, photo-collages, and paintings never made it to the Getty. However, the show, which originated at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, traveled to the Tate Modern in London, and then, so to speak, died on the vine for reasons we know too well (scheduled L.A. dates had been April 21-July 26, 2020).

There is a catalogue, though, and it gives a good idea of what would have been.

Dora Maar, born Henriette Théodora Markovitch (1907-1997), was a minor but integral player in the Parisian Surrealist circle that included her friends and associates André Breton, Paul Eluard, Man Ran, Leonor Fini, and Jacqueline Lamba. She was the model for Picasso’s “Weeping Woman” of 1937, although I don’t think that her somewhat similar portrait of him is called “Weeping Man.”

As Amanda Maddox writes in the catalogue, “Between 1930 and approximately 1939, Maar produced fashion, advertising, architectural, portrait, and nude photographs on assignment or commission for popular magazines, books, fashion houses, beauty companies, and private individuals.” During this time she was also creating photomontages that are clearly in the Surrealist vein, her introduction to that group occurring in 1933.

It may have been inevitable: “Maar possessed a Surrealist sensibility and a sense of the absurd from a very young age,” says Karolina Ziebinska-Lawandowska. Surrealism tends to mesh disparate elements, the resulting imagery giving a bit of a jolt to the viewer (think of René Magritte), and Maar’s photomontages achieved this.

Her subjects varied widely, as Maddox has indicated. During the 1930s, Maar photographed for the so-called erotic magazines (the revues de charme) and there are several images here of the slim and graceful model (and athlete) Assia Granatouroff, which predictably are more artistic than titillating. And then in 1933 Maar traveled to Barcelona and, the following year, to London, where she photographed people on the streets, many of them down on their luck as the Great Depression lingered. There’s a spontaneity in these images reminiscent of Vivian Maier.

Dawn Ades describes this work in greater detail: “Roaming the streets of Paris, Barcelona, and London with her Rolleiflex, Maar penetrated a different world from her studio photographs of commissioned portraits, fashion, and glamorous nudes. The street characters on whom her lens alights tend to be grotesque or pitiable, ragged, poverty stricken, seen with a blank directness light years away from the velvety shadows of the studio.”

The gelatin silver prints further add a sense of despair if not desperation.

Pages 120 and 121 of “Dora Maar,” with “Untitled (Dream” (1935) and “Untitled (Reproduction of a 1900s photograph by C. Bonfort)” (ca.1935) on the left and “Untitled” (1935-36) on the right

On Picasso’s part, he may have motivated Maar’s return to painting, which she had done earlier, and there’s an ample amount of it for us to look at. However, the thought that these could be neglected gems never occurs to me. They range from the semi-abstract in the 1940s to the very abstract in the 1980s. More impressive are the photomontages (like the peculiar “29, rue d’Astorg”) and the photographs, especially her portraits of other artists (Breton, Eluard, Picasso, Lamba, etc). I’ve always been taken by Maar’s photo of a strange plaster sculpture by Giacometti that Breton included in his 1937 book, “L’Amour fou,” or “Crazy Love”.

A crisis point came in the mid-1940s when Maar was hospitalized after a nervous breakdown, before parting for good from Picasso the following year, which was also the year that her close friend Nusch Eluard (wife of poet Paul Eluard) died suddenly from a cerebral hemorrhage. But Maar kept working through the 1980s, and then passed away during the summer of 1997.

The catalogue is a nice tribute to her and it’s unfortunate we missed an opportunity to view her work with our own eyes. Perhaps at another time it will come to L.A., and a piece can then be written with the title, “Dora Maar: No longer a footnote.”

Dora Maar is available from Getty Publications, (800) 223-3431, or visit getty.edu/publications. ER