Gillman of the 509th: A mother’s son

Best friends Jerry Seymour and Marvin Gillman were members of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion and both only sons. Photo courtesy of the author

There were many thousands like Marvin, kids who graduated

from high school just in time to be thrown into a world war

by Ivan G. Goldman

Early on the morning of August 15, 1944, my cousin Tech 4 Marvin Gillman and 15 other men of Company B of the Army’s elite 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion followed Captain Ralph Miller out the door of a C-47 and parachuted into the blackness. They were part of Operation Dragoon, code name for the invasion of Southern France. Their intended destination was Le Muy, a village about 10 miles inland from the resort town of St. Tropez.

The mission of the 509th was to kill or capture enemy forces, seize surrounding roads and hold them until relieved by amphibious assault troops.

Their plane, like the 44 other C-47s in the attack group, had no navigator, just a pilot, and co-pilot, who became confused and lost track of the formation. When the pilot turned on the green jump signal, hoping he was over Le Muy, he was actually skimming over the Mediterranean, probably 15 miles out to sea, the Army would conclude later.

Marvin and his buddies, each carrying approximately 100 pounds of gear wrapped around them like chain-mail, plunged into a rolling sea and sank like steel pilings. No trace of them was ever found.

“They had no chance,” laments Charlie Doyle, who was president of the 509th PIB Association. He’d also made the jump into Le Muy. The lost stick (planeload of paratroops) is an integral part of the outfit’s history and recalled at every reunion.

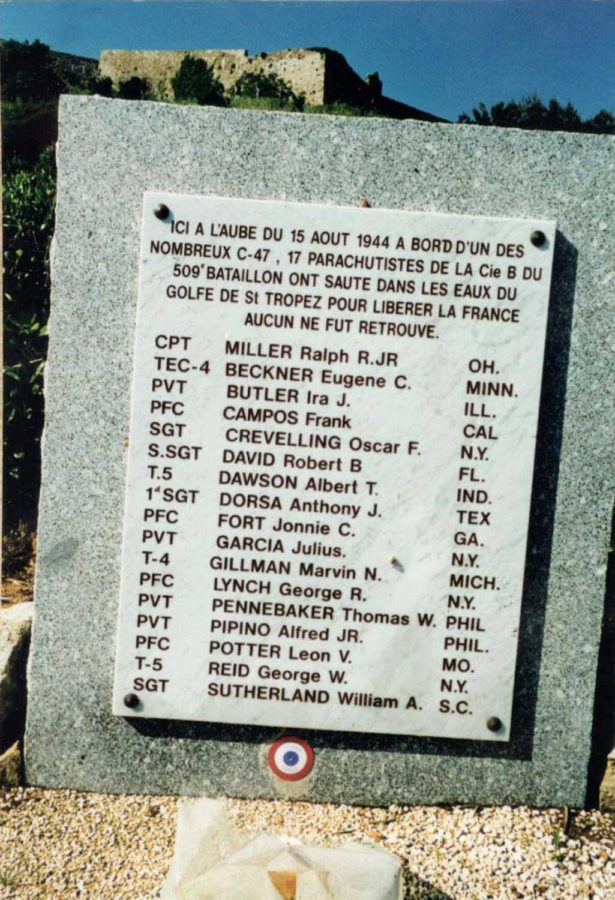

A monument to the 17 soldiers of the lost ‘stick’ of Company B of the Army’s elite 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion, on the beach at St. Tropez. Photo by Ivan Goldman

Marvin was 19, an only child, the son of Solomon and Belle Gillman of Union Pier, Michigan, where they owned a small cafe. Belle was my father’s sister. There were many thousands like Marvin, kids who graduated from high school just in time to be thrown into a world war against the Third Reich and Imperial Japan. Before the drop into France, Marvin had already endured terrible battles in Italy, where he’d been wounded in the fight to hang onto the precarious Anzio beachhead.

He was a larger than life figure in my family, his brief tenure on earth handed down to me in brief whispers, mysterious folklore. Belle, my favorite aunt, didn’t want him declared Killed in Action, preferring the Missing in Action definition even though this placed a hold on his G.I. insurance.

My older sister Phyllis had actually met Marvin. “If we don’t remember him,” she once said to me, “it will be like he never lived.”

Marvin, called Gil by his Army buddies, is commemorated among the missing at the U.S. military cemetery in Draguignan. France. My wife Connie and I visited there once. On the beach at St. Tropez, just behind the city hall, there’s a modest monument to the 17 members of his lost stick.

Over the years I began to feel a stronger obligation to this cousin I could never know. I came to realize I was as close to him in blood as anyone in the world and that I should try to resurrect a memory of him. This was about 20 years ago. The Pentagon sent me his personnel file, and almost miraculously I gained possession of a scrapbook containing all the letters he’d sent from overseas. Through the 509th association, I spoke with many veterans from his outfit. Our phone calls were bittersweet. So many of their friends had died in battle.

The unit fought all the way to Belgium, and after the Battle of the Bulge, fewer than 50 were left from a battalion of 580. The 509th wasn’t part of a division of thousands or even a brigade. “When you’re from an independent outfit like ours,” a survivor said, “and do that kind of fighting for that long, there aren’t so many left to tell about it. The story gets lost.”

Marvin’s letters are un-embarrassingly sweet and loving. They show the Gillman family was a team of three, unafraid to reveal their deepest feelings to each other:

“Mom, it will soon be Mother’s Day. Well, my darling, I can’t give you anything at all. Just remember my thoughts are forever with you. My love isn’t defined by writing. It is a bond between the three of us…. Well, I must stop. Take special care of yourself. God Bless you both. I love you so darn much – Your Loving Son, Marvin.”

He used to send money home and instructed his parents to spend it on themselves. He played jazz saxophone and second base on the battalion baseball team. The war had made him a teenager of great maturity. Although he was tremendously pr0ud of being a paratrooper in the 509th, he was also capable of showing compassion for a young man back home who somehow didn’t serve. “Be sure to give him my regards and tell him I don’t hate him.”

He repeatedly ordered his parents not to worry, that he was fine, but then, perhaps perceiving his future, he instructed them to give away his basketball shoes. He and his best friend in the 509th, Jerry Seymour, were both only sons. “We always talked about it,” Jerry said. “We said if one of us ever got it, we would go back and see the other’s folks. I just couldn’t do it. If I’d gone it would have been terrible.” Despite suffering severe frostbite in both feet in Belgium, Jerry would later become a mail carrier and retire in Lindstrom, Minnesota.

Marvin Gillman’s Purple Heart and Battalion badges.

On March 8, 1944, Marvin wrote, “Hope you received my Purple Heart. Don’t go bragging too much about it. If anybody asks what it is from, just tell them I won a ping-pong tournament.”

Two days earlier, he wrote, “It seems by some stroke of good fortune my buddies are all in the same hospital. We are just having a roaring good time here…. Boy have I made friends over here. I mean real friends. I would give them the shirt off my back and visa versa.”

Jerry was one of those friends in the hospital. “While we were there, Mount Vesuvius erupted,” he said. “We’d see it every night. It was so beautiful with all the flames shooting out.”

Marvin spent one semester at Michigan State before he joined the Army and volunteered for jump school. As a high school senior he wrote an essay about what he expected from college – “a means to earn a living but also to make a cultured person out of me. A person who will be able to appreciate art, music, and poetry. To be able to get joy from life because of simply knowing what goes on about me.” His teacher deducted points for the sentence fragments.

Marvin got to see Naples and Rome. In Rome, he and Jerry hired a carriage. “We made a kind of tour and ended up at the Coliseum,” Jerry said. “We were really impressed. We were bivouacked then at Lido de Roma, Mussolini’s summer retreat. We were training for France. We had a pretty good summer there before we took off for that mission.

“We played baseball there on the 509th team. He was one heck of a second baseman. When we played another team we’d all throw in money. We’d have as much as $500 on a game. When we won, we’d throw a party.”

Frame this

After taking their objective, battalion members searched the beaches for miles but could find no sign of their comrades, who eventually were numbered among the approximately 415,000 U.S. military dead of World War II.

Going through Marvin’s scrapbook, I came upon a unit citation awarded to the 509th for its actions in Italy. After sustained shelling, the battalion, forming a thinly occupied segment of the line, was attacked by a much larger force. The soldiers “fought desperately, disdaining retreat, engaging the overwhelming and constantly increasing German force with rifle butts and even fists.”

On the back of the citation, signed by Lieutenant General Mark Clark and dated June 5, 1944, Marvin had written, “Frame this,” but no one ever had. Decades later, my wife and I carried out his wishes. It’s on our wall beside the Purple Heart he didn’t really win in a ping-pong tournament.

Ivan Goldman, is a Redondo Beach writer and New York Times Best-Selling author. His most recent novel is The Debtor Class (Permanent Press).