Preston Sturges a prescient screenwriter

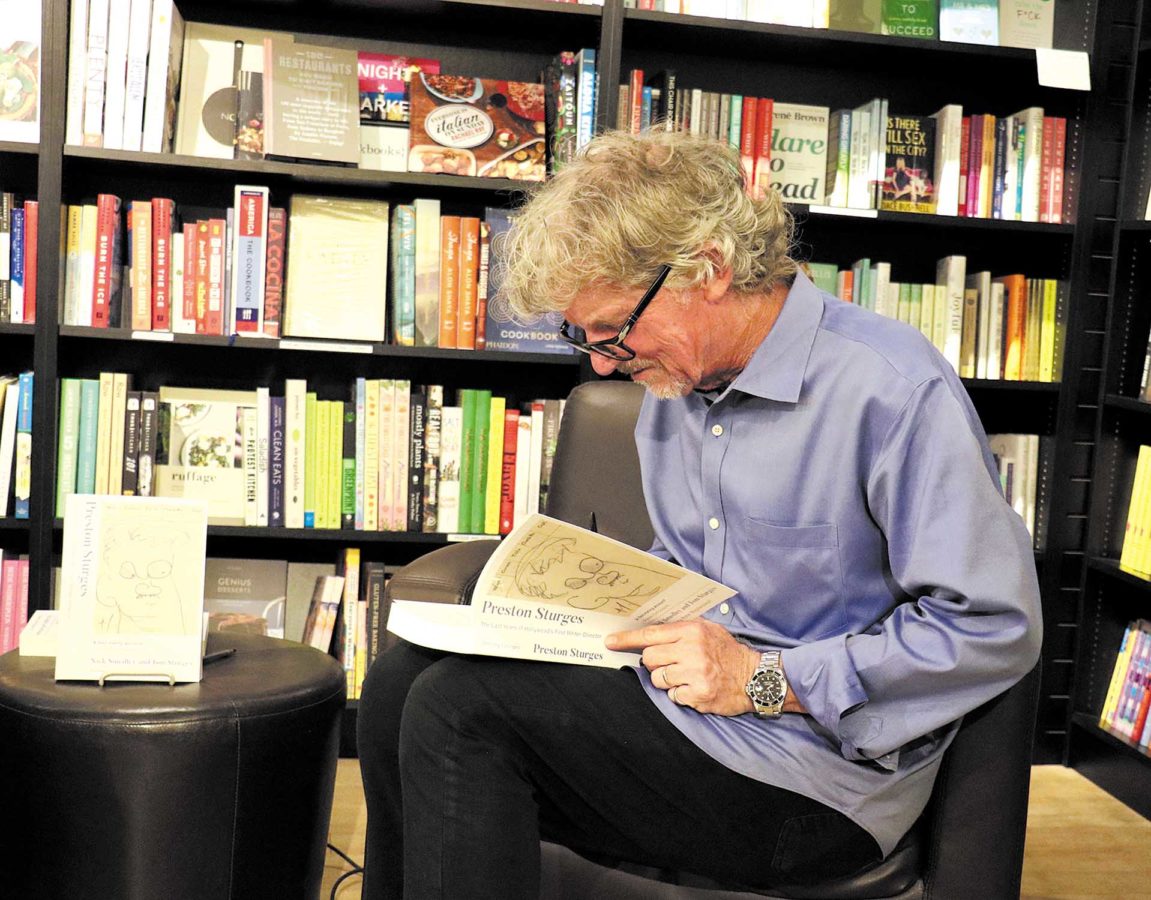

Tom Sturgess reads from his biography of his father, screenwriter and director Preston Sturgess, at Pages Bookstore last Thursday.

The Hollywood legend’s struggles disclosed in biography by son

If Thursday night’s book signing at Pages Bookstore was a Preston Sturges film, it would have been called “The Manhattan Beach Story.”

The plot summary: a son who worships his long-dead, celebrity father as a hero finds some old letters and diaries that give him a new perspective on his dad as a struggling, flawed human being late in his once-glorious life. It’s a transformative discovery that just makes him love and honor him even more — to the point that he eventually decides to write a book about his dad’s decline and death.

“Preston Sturges: The Last Years of Hollywood’s First Writer Director,” by Manhattan Beach resident Tom Sturges and co-author Nick Smedley, is the historically important and wildly entertaining result of that serendipitous discovery.

By the time he had written and directed a string of classic comedies, including like “The Palm Beach Story,” “The Lady Eve” and “Sullivan’s Travels” in the early 1940’s, Sturges was the artistic equal of contemporaries John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, Billy Wilder, and John Huston. The brilliantly imaginative storyteller single-handedly elevated the primitive 1930’s screwball comedies – heavy on slapstick, light on clever dialogue — into a new, vastly more sophisticated art form.

But because almost all his great films were produced during a frenetic five-year creative explosion from 1939-44, Sturges has largely been forgotten by the general public while the others have lived on because their artistic primes lasted several decades.

In 2006, after Tom’s mother Sandy died and he was cleaning out her house, he found some old files containing long-ago letters between his parents, as well as diaries, unpublished screenplays and other memorabilia from his father. The papers revealed difficulties his mother, nearly 30 years younger than his father but just as headstrong, independent and quick-witted, had never hinted at.

“My mom had spun a beautiful fairy tale about their romance, when in fact they were not all lovey-dovey. They were sometimes really mad at each other,” the Manhattan Beach resident said. “But she wanted to have me revere my father. I love that she spun the story for me that way, to give me a father as a hero.”

Tom was born in 1956, after his father left Hollywood for Europe. His mother brought him and his brother Preston back to Hollywood in 1957 and he never saw his father again. They left his father alone in Paris with his ruined career, his alcoholism, his three-pack-a-day cigarette habit, and his mistress. His initial vision of his father was formed by what his mother had told him as a child. Those stories make up the four “interludes” the authors use to separate the book’s sections.

Tom kept the papers to himself for a decade. Then he was contacted out of the blue by Smedley, who was interested in writing yet another Preston Sturges biography.

But Smedley, an accomplished Hollywood author and scholar, was late to the party. After 17 Preston Sturges books including many biographies, several film-by-film critical appreciations and even a posthumously published autobiography in 1990, his son felt there was little left to say about his dad.

Sturges suggested taking a different angle that they could work on together with the new source material: a book about his father’s life in the 1950s, about his years of decline and failure, the years when his golden touch disappeared, his life fell apart, Hollywood turned its back on him, his finances cratered, and he lost his Sunset Boulevard restaurant/nightclub called The Players.

The idea equivalent to the old sportswriter’s maxim that the best stories are to be found in the loser’s clubhouse. The quotes from the winner’s clubhouse are boring and predictable: it was a team effort, we’re all in this together, and blah, blah, blah. But in the loser’s clubhouse, you get the true story, the real emotions, the raw, unvarnished human truth that lurks beneath the surface.

The result is a fascinating and revealing book about his father’s 10 years of decline, leading to his death, a decade when he struggled every day to regain his status as Hollywood royalty. It was a decade when he never lost faith that there would be a second act for him. Always there was a new idea, a new project to work on, and always the slow realization that once again they weren’t going to happen.

His sudden death of a heart attack in New York’s famed Algonquin Hotel in 1959 ended his comeback dreams, leaving all those biographers to focus on his half-decade as a great director and before that his full decade as a leading playwright and screenwriter. It was a status he used to force the rigid studio system into allowing him to direct his own screenplays, starting with the 1940s “The Great McGinty.” A major hit – it won the first Oscar given out for best original screenplay — its premise was that absolutely anybody, even a bum off the street, could rise to great political heights if they were willing to play ball with the hidden power brokers. That theme – that anyone can rise to the top through fraud, bluff and plain old luck – appeared frequently in his films.

It was a prescient premise for a story written 80 years ago.

Sturges, 63, made his own professional mark as a successful music business executive who understood how to work with talent. Thursday night could have been a tough night to draw a crowd to a place that didn’t have a big-screen TV on the wall. The Dodgers were playing their opening game in the playoffs and the Rams were playing a crucial, early-season game in Seattle.

So Sturges brought along John Ireland, the well-known Lakers broadcaster, who happens to be one of his many golf buddies, to conduct the Q&A session in front of what turned into a standing-room-only crowd.

“I’m so excited to hear what Preston Sturges’ son has to say,” Nancy Humbarger of Manhattan Beach said a few minutes before the event started. “‘Sullivan’s Travels’ is one of my favorite films.”

Kork Lowry of El Porto had a different favorite.

“I just saw ‘The Lady Eve’ a few nights ago on TCM,” he said. “I love that film.”

Ireland brought out the best in Sturges, a compulsively funny man who has his father’s restless, creative imagination. It was clear that Ireland had enjoyed the book, which includes lists of Sturges’ unproduced story ideas that still have great promise and unproduced inventions – like the expand pants that expand as your waist expands – that still make sense.

There is also a moving, reverential forward by director Peter Bogdanovic, who nominates The “Miracle of Morgan’s Creek” as the funniest of all Sturges’ films.

Among the many interesting points, Sturges made about his father was that even though he was known as the master of the screwball comedy, he never used a generic joke to get laughs. Instead, his father’s characters spoke their truth, and if the audience found it funny, it was an organic part of the story.

The best-known example of that kind of witty, naturalistic dialogue comes when Barbara Stanwyck is plotting her romantic revenge against Henry Fonda in the Lady Eve: “I need him like the ax needs the turkey.”

The audience — some familiar with the famous line, some not — laughed loudly.

“That was her absolute truth,” Tom Sturges said.

Contact: teetor.paul@gmail.com. Follow: @paulteetor.