The Transcendence of Willie

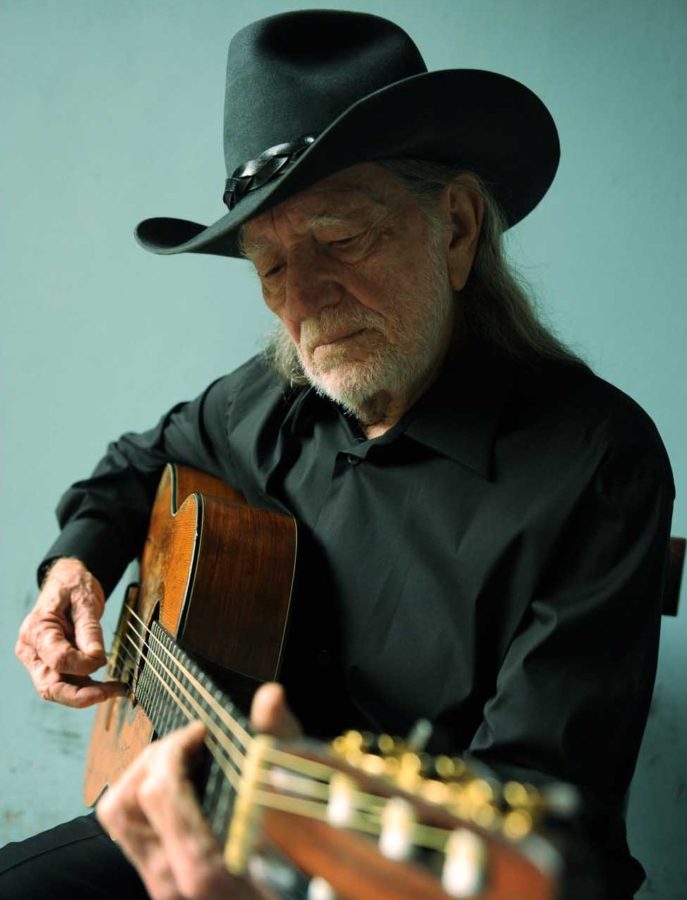

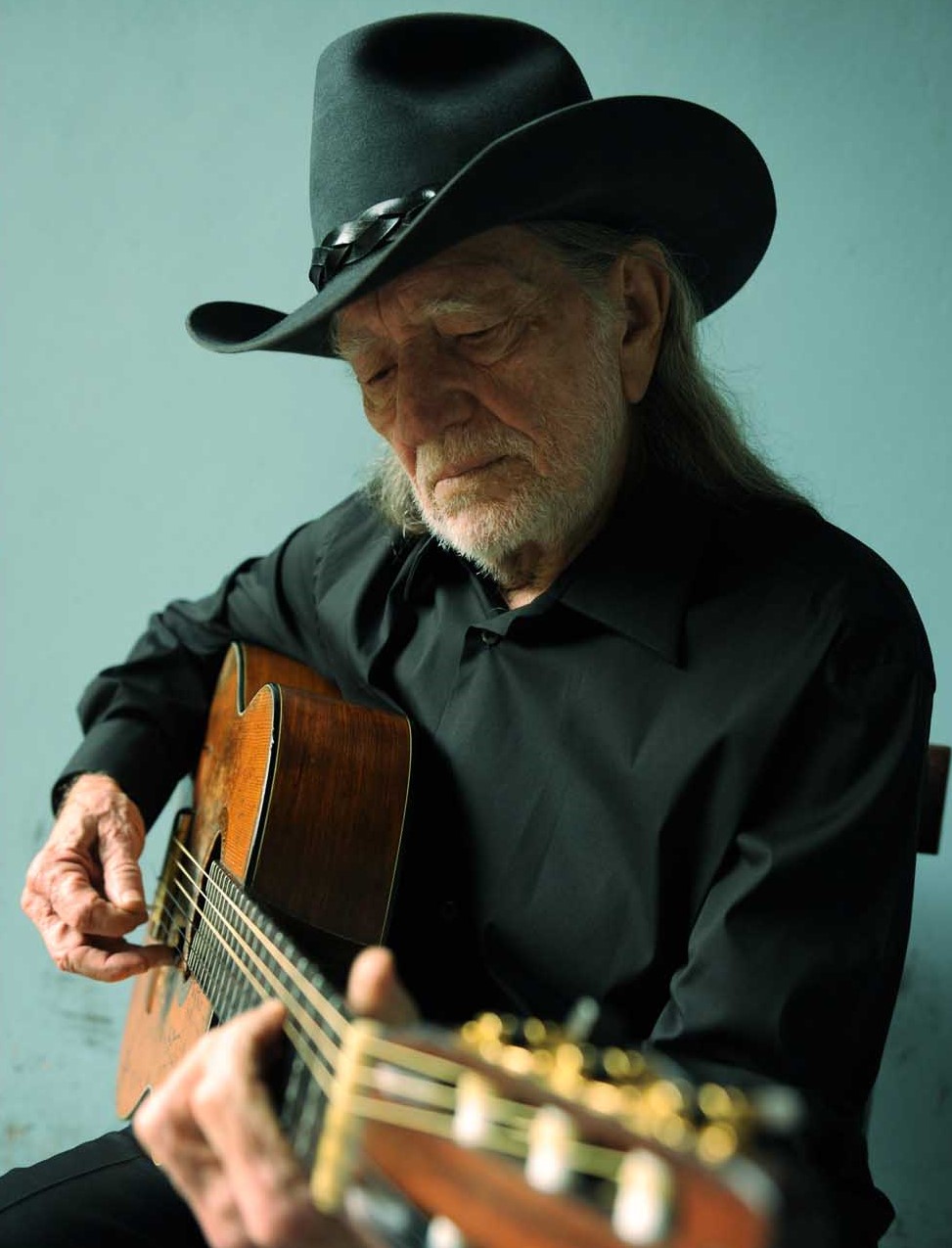

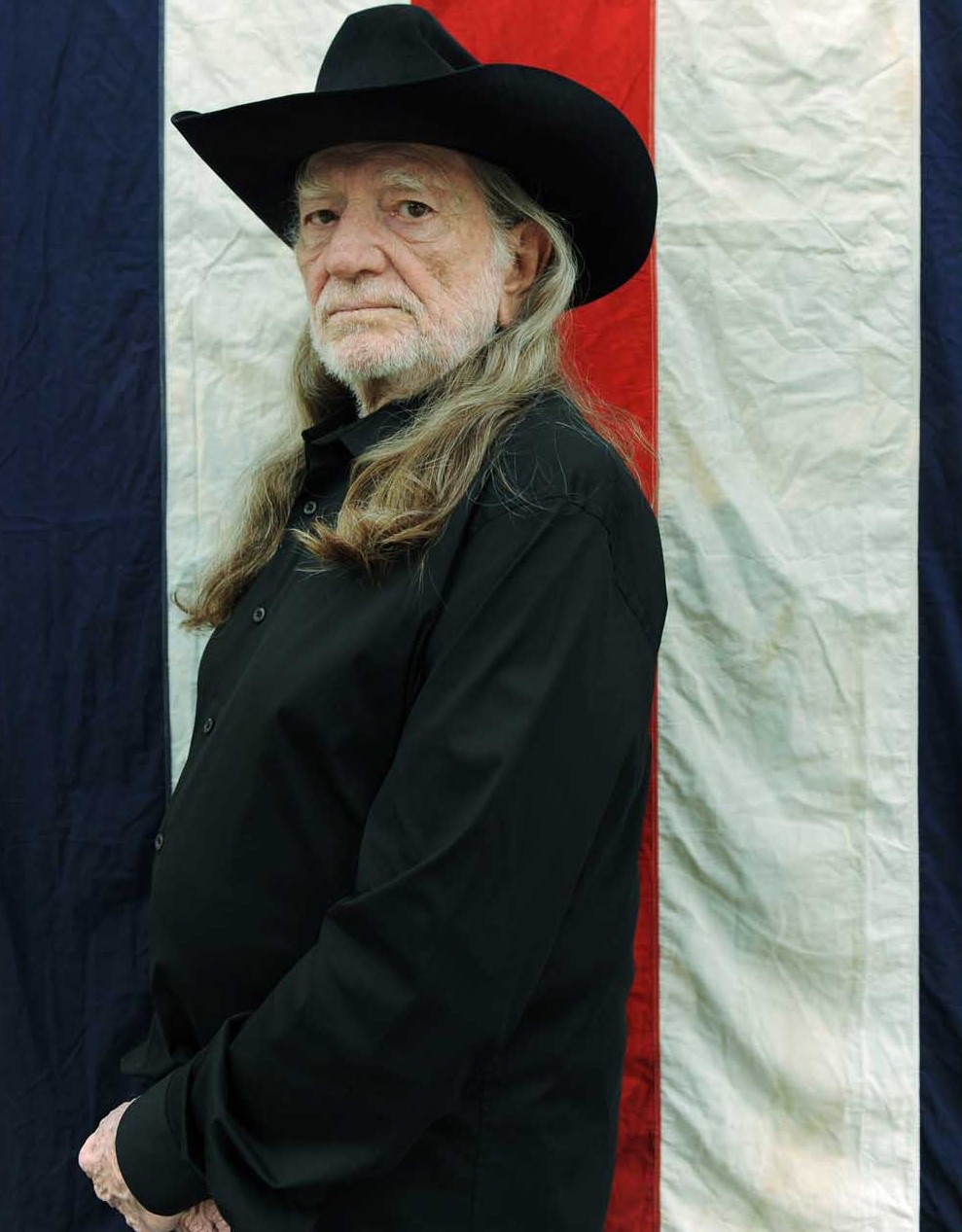

Willie Nelson. Photo by David McClister

Three days before Christmas 1969, Willie Nelson and Hank Cochran wrote a song together titled, “What Can You Do to Me Now?” Both worked in Nashville and were known as “songwriter’s songwriters,” a nice way to say they wrote songs and other people made hits out of them.

Nelson was particularly frustrated with this state of affairs. He’d written some huge hits, such as “Crazy” and “Funny How Time Slips Away,” which had been sung by stars Patsy Cline and Ray Charles, and made him a nice living. He’d built a ranch near a little town called Ridgetop on the Tennessee-Georgia border and a whole brood of his family and friends lived there. But his own career as an artist had stalled. Record label executives thought his sinewy voice was too idiosyncratic for popular appeal. One label had dropped him, another refused to promote him.

Two days before Christmas, Willie was at a party in Nashville when he received a frantic phone call from his nephew. His Ridgetop home was on fire. By the time he got there, the house was a smoldering ruin, though no one had been hurt. Willie fought past the firefighters and worked his way to his bedroom. Amid the flames, he found a guitar case stuffed with two pounds of weed, enough in those days to send a man to jail for a long time. Then he found a second case containing his treasured guitar, Trigger.

“When you write a song called ‘What Can You Do to Me Now’ and almost immediately afterward your house burns down,” Kinky Friedman, Willie’s longtime friend, would later write, “it would appear that somebody is trying to tell you something.”

His wife was weeping. Willie was unfazed.

“It’s all gone, Willie” she told him, according to his memoir, It’s a Long Story. “It’s all gone up in smoke.”

“All that’s gone is the material stuff,” Willie replied. “Our spirit ain’t gone. Our spirit is stronger than ever.”

He then took his weed, guitar, and family, and headed back home to Texas, where it had all begun. His choice would upend country music, and the rest of American culture with it.

Fifty years later, as Nelson takes the stage at the BeachLife Festival in Redondo Beach on May 5, what those in attendance will experience is not only a performance by one of the greatest singers, songwriters, and guitarists of our time, but a glimpse at a genuine American legend.

Willie Nelson, who plays at BeachLife Festival in Redondo Beach May 5. Photo by David McClister

The story is often told of how Willie Nelson returned to Texas, grew his hair long, replaced his fancy Nashville clothes with jeans and a bandanna, and united hippies and rednecks under the happy banner of music and general raucousness at his annual Fourth of July picnic.

“They all sat around and drank beer and smoked some dope and listened to some good music and found out that there wasn’t a lot they had to be afraid of,” Nelson later told The New York Times. It’s a sweet and true tale — that first picnic, at Dripping Springs, Texas in 1973, attracted 40,000 people. Rolling Stone called it “country music’s Woodstock moment.” But its import is perhaps less about bringing those tribes together and more about the unifying sway the man and his music have had ever since.

Willie Nelson is one of our master songwriters, guitarists, and singers. He’s written 2,500 songs, scored 50 number one hits, and sold 40 million records. He is known on a first-name basis by millions of people in a way only a handful of artists have ever been. Yet Willie is even more than the sum of his songs. Friedman has described him as the “hillbilly Dalai Lama.” Willie is the closest thing America has to a spiritual hero. If you say Willie’s name, more often than not it will elicit a smile, regardless of age, gender, or even musical taste.

“The Hells Angels love him, and so do grandmothers,” said Mickey Raphael, who has played harmonica with Willie since 1972.

When Willie left Nashville, he also left behind any notion of anything but serving his music as purely as possible. He’d seen how artists like Leon Russell and the Grateful Dead, both who, like himself, had roots in country and blues, had re purposed the music as an act of rebellion.

“The new world represented by the Grateful Dead…was only new in appearance,” he later wrote. “That appearance appealed to me because it was bold and creative and said to the world, ‘To hell with what you think. I’ll dress any way I please.’ The music might have had a new configuration, but hell, I could trace it back to Lightnin’ Hopkins…The music was as old as time.”

Raphael remembers an image that struck him well before he met Willie. In 1971, he was on the same label as Nelson, RCA, which gave him access to the record vaults. The cover to a record titled Willie Nelson & Family was a photo of about 20 people gathered around a bonfire. There are woods and a green field behind the group, who are shaggy but somehow elegant in their togetherness. On the far left, Willie’s sister (and piano player) Bobbie looks dignified in her zebra-striped shawl and carefully coiffed hair. On the far right, drummer Paul English kicks a leg out and smiles like a well-groomed wolf, wearing bright red pants and a cape, befitting his former life as a pimp and gang leader. Willie stands cooly in the middle, wearing a cowboy hat and a long brown coat and looking both the more reasonable and deadly of the outlaws.

“I got it just because [of] the record cover,” Raphael said. “And then I listened to Willie’s voice and guitar, and it really piqued my interest.”

A year later he was invited to a “picking session” by University of Texas football coach Darrell Royal and found himself mesmerized by the singing and guitar playing of another guest, Willie.

“He did ‘Night Life’ and ‘Funny How Time Slips Away’ and I recognized those songs from Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles,” Raphael said.

Willie invited him to sit in at a show. One show lead to the next and suddenly it was 1973. One day Willie asked English, who was also the bandleader and accountant, what they were paying Raphael.

“We are paying him nothing,” English said. “He’s just coming on his own.”

“Double his salary,” Willie said.

Willie, in his memoir, recalled how with the addition of Raphael he began to envision his group as more than a band.

“I began to see how, rather than as an occasional sit-in, he could become part of my family — a loose term that I started using to describe my band,” he said. “As a depiction of people coming together to make music, I like the term ‘family’ more than ‘band.’ It’s a warmer word that suggests genuine care and love.”

Music and family had always been intertwined in Willie’s life. He grew up in Abbott, Texas, population 200. His parents Ira and Myrle Nelson married as teenagers and had two kids, Bobbie and Willie, by the time they were 19. Just three days after Willie’s birth, his parents dropped him and his sister at their grandparents house and took off for points unknown. Their marriage would end within the year. Alfred and Nancy, better known as Daddy and Mama Nelson, would raise the kids, and they would do so with music at the forefront of their upbringing.

“Our grandparents were students of music and studied the music they received through mail-order courses by lamplight every night after supper. Our grandmother Mama Nelson was our music instructor. Daddy Nelson insisted that Mama start teaching us before we started school,” Bobbie Nelson wrote in a section of Willie’s book, Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die. “Daddy Nelson played string instruments, and Mama Nelson had knowledge of music from her father, who taught voice classes at singing schools in Arkansas. Our grandparents were gospel music singers. Daddy Nelson’s voice was very beautiful; he was a tenor.”

Willie’s first memories of music are of being carried by his grandma while she picked cotton and all the field workers sang, mostly spontaneous gospel songs. Everybody was poor and doing backbreaking labor but they sang in praise of God and of life. “I got the notion God was everywhere,” Willie wrote in his memoir. “… Music was offered up to the sky.”

The lessons he took from this were: “Wherever you go, take music with you. Music never has to stop. Let the music keep coming through you. Keep singing and playing and telling your story — no matter how happy or sad — through music. Music will protect you. Music will keep you going.”

Daddy Nelson gave him a guitar and Willie wrote his first song at the age of six. Daddy died of pneumonia when he was seven. Thereafter the music never stopped.

And so after his house burned down in Nashville and Willie returned to Texas, he stripped away all the bullshit that wasn’t music. He assembled his “family” band, which included sister Bobbie, whom he considered a superior musician. Trigger, the classical Martin guitar he saved, was named after Roy Rogers’ horse, and Nelson rode it to liberation. (Nelson would eventually play a hole into Trigger, which, as a classical guitar, was not meant to be strummed with a pick.) In 1975, fresh after being dropped by yet another label (Atlantic), he signed a deal with Columbia and snuck in a clause that gave him creative control of every last note on every record. Then he went to a little studio in Texas and recorded a stripped down, high-concept record inspired by an obscure, dark 1950s song called “The Tale of the Red Headed Stranger,” about a fugitive preacher who has murdered his unfaithful wife and is “wild in his sorrow, riding and hiding his pain.” The record company thought it was a demo and rejected it, deeming it unprofessionally recorded and not commercial enough in its topicality. Country music at that time was at its most overblown, with caricature cowboys, string sections, and as many bells and whistles as possible. Willie invoked his artistic control clause, the record was released and sold well — it went double platinum and included a number one hit, “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.” Many critics consider “Red Headed Stranger” the greatest country record of all time.

Willie instantly became one of the biggest stars in the country. He’d helped create a new genre, “outlaw country,” that may have included a lot of the mythology of cowboys but was really about one thing: going resolutely your own way. The rebellion wasn’t about the clothes or the hair or even the genre. Three years later, in 1978, he made another record the label tried to reject, this one a collection of old jazz standards such as “Georgia on My Mind,” “Blue Skies,” and the title track, “Stardust.” The record not only went number one but stayed on the charts an unprecedented 10 years. It also earned him his first Grammy.

“I appreciated the kind words from the critics,” Nelson wrote in his memoir. “But what pleased me most was the damage done to narrow-minded thinking.”

The outlaw part of Willie’s growing legend wasn’t an act. In 1977, he was jailed in the Bahamas for marijuana possession. He’d been a dedicated weed smoker for a decade, after finding that it made him a lot less angry and a lot healthier than whiskey. He’d be jailed four times for possession, but he didn’t believe he was doing anything wrong so he kept smoking. Two days after he got out of jail in the Bahamas, he flew to the White House to play a show for Jimmy Carter and slept in the Lincoln bedroom. That night, he and a presidential staffer would smoke a joint on the roof of the White House.

He’d later run into an even bigger bit of an outlaw problem, and similarly overcome it like some kind of mystic master. His manager in the 1970s and ’80s had failed to file his taxes. The IRS showed up one day at his ranch in Texas and threatened to take everything. (Willie must have sensed something impending and had shipped Trigger to Hawaii the week before). He owed millions. His new manager suggested declaring bankruptcy. Willie demurred. The manager asked him what he proposed doing instead.

“Have a little toke, play a little golf, take a little nap, and play a little dominoes,” he said.

“All you are doing is preparing for disaster,” the manager said.

“All I’m doing,” Willie replied, “is keeping a positive thought.”

He released two records of various outtakes and new recordings and dubbed them, “The IRS Tapes: Who Will Buy My Memories?” The answer was plenty of people. The records sold well, Willie pulled himself out of debt and kept on rolling down the road, making music with his family and friends.

Willie Nelson is 86 now. He’s watched a lot of his old friends die, from Ray Price to Waylon Jennings to Johnny Cash. His band is still billed as “Family” and is largely intact 48 years after its founding, although two members, Bee Spears and Jody Payne, have also passed away. His son Lukas Nelson, who has that same uncanny tenor voice and silvery, impeccable musicality, is his heir apparent, musically. But Willie is far from done. He’s still on the road, playing two weeks on, two weeks off, about 100 shows a year.

“When I first went to work with him, he was 39,” Raphael said. “And to me, he hasn’t changed a bit in all this time. He’s still the same Willie, the same guy, you know? What you see is what you get with Willie.”

He’s never been afraid of much, and old age certainly isn’t about to change that.

“Oh, we’re all going to die,” Willie told the Washington Post last year. “Who was it, Seneca, the thinker, who said you should look at death and comedy with the same expression of countenance? You can’t be afraid of living or dying. You live and you die, that’s just what happens, so you can’t be afraid of either.”

Raphael remembers a stop on the road a few years back, a benefit show in Idaho, where Willie met the Dalia Lama, who his son Lukas, on an Instagram post, described as his dad’s “soul mate.”

“I’m not sure he knew exactly who Willie was, but he knew he was an important musician. He’s very childlike and laughs a lot. He goes, ‘Maybe we’ll write a song for the Chinese,’” Raphael recalled.

The Chinese, of course, are the reason the Dalai Lama has lived in exile since 1959, when they invaded his native country, Tibet. But as is the nature of things, this is also the reason he has become a worldwide emissary of peace, goodwill, and the power of the human spirit.

“Yeah,” Willie told the Dalai Lama. “We’ll write it together.”

Willie Nelson & Family play BeachLife Festival May 5. See BeachLifeFestival.com for tickets and information.