no images were found

Click arrow to enlarge photos

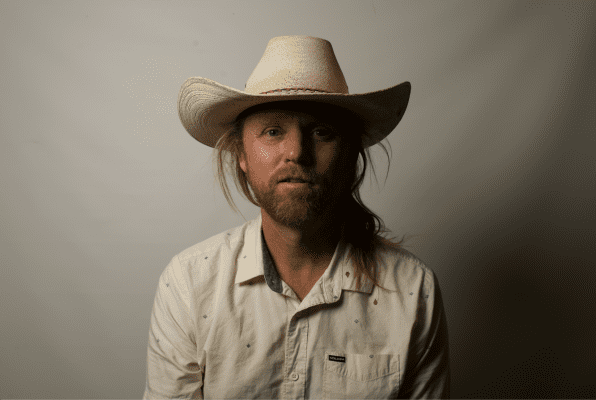

John Van Hamersveld taught a class called “Making Images” from 1975 to 1982 at the California Institute of the Arts. The class was broken up by semester into line drawing and painting. He quit, he writes in the catalogue to his 2013 “Drawing Attention” exhibit at Cal State Northridge, “because the design department…shifted the program focus so it excluded drawing entirely. The idea was that…conceptualizing art as design, you would direct someone else to use their hands to create your work. The view of design…was that design was a service, not an art…So I quit.”

Van Hamersveld was not a traditionalist. The following year he would be introduced to Steve Jobs and become an early adopter of digital design. But by 1982, he had already established an international reputation as both an artist and a designer by refusing to acknowledge a divide between the two disciplines.

He still hand draws with pen and paper. But today, his palette is the computer, into which he scans his drawings. His brush is a digital printer, sometimes a very big digital printer.

no images were found

Click arrow to enlarge photos

On June 28, the public will have the opportunity to judge Van Hamersveld’s coupling of art and design when the Hermosa Beach Mural Committee unveils his 75-foot-long, 19-foot tall “Great Wave” on the side of the Underground Pub and Grill in downtown Hermosa. The committee commissioned Van Hamersveld last December, in the words of its theme committee, to paint the “surfing lifestyle that gave those living here a sense of belonging and a special connection with nature [that] continues today.”

Van Hamersveld began to draw at the family dinner table, where his artist mother and Northrop engineer dad often communicated by sketching on napkins. Drawing was a natural pursuit for their dyslexic child who, happily, was naturally gifted at it.

That gift led him to leave his Palos Verdes home for Art Center in Los Angeles after graduating from El Segundo High School. Palos Verdes didn’t have a high school at the time.

Two years later, in 1963, his brilliantly colored and more brilliantly designed school project, a poster for the “Endless Summer” surf movie, pushed him to the forefront of the ‘60s cultural revolution.

The poster became his calling card. Brown Meggs, who signed the Beatles to Capitol Records in 1963, hired Van Hamersveld as his art director in 1967. Van Hamersveld’s album covers over the ensuing 12 months are collectors items today. They included the Beatles’ “Magical Mystery Tour,” The Rolling Stones’ “Exile on Main Street,” Jefferson Airplane’s “Crown of Creation,” Grateful Dead’s “Skeletons from the Closet,” and Blue Cheer’s “Vincebus Eruptum,” the latter, with its stacks of Marshall amps, louder than the takeoff squeal of a 747.

Van Hamersveld employed a simple device to prevent the required commercial message from compromising his artwork, beginning with his first commercial assignment, a 1962 ad for Bing Surfboards in Hermosa Beach. The ad ran on the back page of Surfing Illustrated, which Van Hamersveld co-founded while still at Art Center with Riviera Village printer Walt Phillips. Hermosa surf photographer Leroy Grannis was the photo editor and Hermosa ski and surf filmmaker Warren Miller a contributing writer.

After carefully choosing and sometimes hand lettering the type, rather than placing it over the art, as commonly done, he used the type to frame the art.

His success in reconciling art and design was validated when both the New York and Los Angeles museums of modern art added his “Endless Summer” and Jimi Hendrix Pinnacle concert posters to their permanent collections.

“There was Andy Warhol among all this,” he acknowledged in a Beach magazine interview last November. “What he brought is he was able to show you there are two sides to the arts. One was more academic and the other was commercial art. Pop art or popular culture embodied everything around us at the time. And so we were able to see in that, as a generation, an alternative to the military complex, the life that our parents lived in.”

Warhol was an ad designer when he dismantled the distinction between fine art and commercial art with the Los Angeles exhibit of his “32 Campbell’s Soup Cans” two years prior to Van Hamersveld’s “Endless Summer” poster.

The now 74-year-old Van Hamersveld traces his aesthetic to his immersion in the South Bay surf and drug culture of the ‘50s and ‘60s.

He surfed for the first time when he was 12 at the Cove on a 12-foot, Tom Blake kookbox, loaned to him by Jared Eaton, whose older brother Mike was a shaper for Bing and is still one of the sport’s preeminent shapers.

“We put it on a World War l stretcher and pushed it for two-and-a half miles along PV Drive West to the trail leading down to the Cove,” Van Hamersveld recalled.

His first surfboard was a Jacobs. His father bought it for him on his 14th birthday in 1955 at the Velzy-Jacobs shop in Venice. No one was at the shop when they arrived to order the board. Van Hamersveld described the experience in near mythic language.

“I suddenly felt like I should look to the north into the fog and there appeared a green Dodge pickup truck with a deer tied over the hood,” he remembered. “Velzy quickly hopped out of the passenger’s seat to greet me, while Jacobs lingered to look over the deer on the hood….Jacobs pulled the bows and steel-tipped arrows from inside the cab. I had never seen anything like this in my young life outside of a Robin Hood movie.”

“Hey, we were in the Malibu Mountains hunting,” Velzy said. “It’s great up there. Lots of deer to hunt.”

Lifeguard John McFarlane watched Van Hamersveld grow up in front of his Torrance beach tower.

“Hammer surfed with a hot bunch. He was a good surfer, but a better skier. I bought his skis,” recalled McFarlane, a 2014 Hermosa Beach Surfer’s Walk of Fame inductee. Other members of the Torrance beach crew, McFarlane said, were Rick Irons (father of three time world champion Andy Irons), Jeff Hakman (future world champion and Quiksilver co-founder), John Mel (father of Mavericks big wave surfer Peter Mel), future pro and board builder Mike Doyle and Jacob’s team rider Chris Bredesen.

On weekends, Van Hamersveld traveled to Rincon and San Onofre with fellow Palos Verdes surfer Phil Becker, who was three year older and had a car. Becker is also a Hermosa Surfer’s Walk of Fame inductee.

After school, the surfers hung out at the Hermosa Foster’s Freeze, across the street from where his mural is to be unveiled.

His early drawings, Van Hamersveld said, were inspired by weekly visits to the the Palos Verdes Drugstore.

“Like all kids in PV, my awareness of cartoons started at the magazine rack, next to the fountain, with MAD magazine and Playboy, if someone didn’t stop me from looking at the Vargas illustrations. Hot Rod Magazine with Von Dutch’s pinstriping was there too,” Van Hamersveld said.

Rick Griffin, creator of Surfer Magazine’s Murph the Surf cartoon, was one the kids Van Hamersveld would meet up with at the magazine rack. He credits Griffin for his “Endless Summer” poster assignment.

“Without Rick, I would never have met Bruce Brown,” Van Hamersveld said. Griffin introduced Van Hamersveld to Surfer publisher John Severson, who named Van Hamersveld his art director. “Endless Summer” filmmaker Bruce Brown came to the magazine looking for an artist to do a poster for $150, which is all the money Van Hamersveld has ever made from the poster.

Van Hamersveld’s emergence from the South Bay’s surf culture and his Zelig-like presence in pop culture throughout the ensuing decades, make it appear preordained that he would receive the commission for Hermosa’s surfing mural. For the 1984 Olympics, he wrapped the Los Angeles Coliseum in a mural of track and field athletes. In 2010, he created the Freemont Experience in Las Vegas, a 90-foot overhead, four-block-long light mural with 12.5 million computer-controlled LED lights.

Van Hamersveld came to the Hermosa Beach Mural Committee’s attention last November through the Beach magazine article. He had moved back to Palos Verdes with his wife Alida Post in 2013, after being away for over half a century.

Prior to commissioning its previous five murals, the committee sent out requests for proposals. But Van Hamersveld’s background made a competition for the commission appear superfluous.

In December, he was invited to meet with George Schmeltzer, a former mayor, and his fellow theme committee members architect Dean Nota and Nota’s artist wife Linda Jo Russell at the Nota-Russell home.

In preparation for the meeting, Nota printed out a 24-inch by 40-inch picture of the proposed mural wall.

“Before the meeting, I wasn’t sure John would be a good match because his work is more abstract than the styles we’d done in the past. I was concerned he might be a hard sell to the full committee,” Nota said.

Then, shortly after the meeting began, Nota said, “John took out a marker and started drawing on the printout. It’s rare to see something like what he did. It showed his genius. In my work, I try to establish the essence of a design solution. But I need time. He did it spontaneously, right there in front of us, with a simple line drawing. I remember thinking, ‘Wow, he just nailed it.’ I said to George and Linda Jo, ‘That is the perfect mural for the site.’”

Schmeltzer was equally impressed.

“We wanted a mural that honored Hermosa’s surfing history without having to select a particular surfer, hanging 10 or doing a cutback with Palos Verdes in the background. We see that every day of the week. We wanted to move beyond that with something that speaks to surfers and non surfers,” Schmeltzer said.

But Schmeltzer had reservations about how the rest of the committee would respond.

“This is not a public arts project. It’s a history of Hermosa Beach murals project, so the parameters are different. We had to convince the committee that his design was definitely Hermosa, and not something that might appear equally at home in Huntington Beach or Santa Cruz,” Schmeltzer. “We don’t roll over dissent,” he added, indicating the need for consensus.

Van Hamersveld brought a cardboard model of his proposal to a meeting of the full committee at Chuck Sheldon’s Hermosa Strand home.

“These are my contemporaries. I’m used to making presentations to much younger audiences,” he said in recalling his apprehension at the the initial meeting.

Sheldon had a similarly uncomfortable reaction.

“I was surprised that behind the round black rimmed glasses and black fedora, he was my age. I had difficulty grasping what he was going to do for us,” Sheldon said. “He talked about it being iconic. I’m a basic idea guy when it comes to art and had no idea what he was planning to come up with and was not favorably disposed. It didn’t say Hermosa. It could have been Hawaii. But Schmeltzer kept me on the straight and narrow and by the end, I was a believer.”.

Following the meeting, Van Hamersveld’s studio became buried in increasingly developed ink sketches on large sheets of vellum.

“Ideas come from the imagination and the imagination is like a cloud,” Van Hamersveld said in explaining his process. “The designer crops out a section of the idea and draws it on napkins and pads. It’s not well defined. We need references, people, waves, to harden up the image. I go through tissue after tissue, balancing the positive and negative space to get balance and [before loading his palette], to ‘see’ color, as five percent of this color, 30 percent of that color.”

In late January, Van Hamersveld emailed the theme committee a more developed, colored sketch of what he had shown them at the early meetings.

A large wave paid homage to 18th century Japanese artist Hokusai’s famous “Great Wave at Kanagawa.” Three silhouetted surfers referenced Van Hamersveld’s “Endless Summer” poster.

The surfer in the foreground held a contemporary short board. Behind him, a second surfer held a longboard from the Golden Era of Velzy-Jacobs. In the distance was a third surfer with a kookbox from the Doc Ball era.

Clouds and suns exploding like pinwheel fireworks pulled together what was to be the nearly nearly block long mural.

The colors were bright, but not as blinding as his ‘Endless Summer” poster because, he explained, dayglo inks aren’t available for digital printers.

Last week, files of the mural were sent to Spin Imaging in Long Beach, which prints window laminates for skyscrapers, graphic designs for Formula 1 race cars and heat resistant laminants for Virgin Galactic space ships.

“The Great Wave” will be printed on four 18.5-foot long sheets, which will be tiled together this week on the side of the Underground Pub and Grill, then covered until the June 28 unveiling.

“Half the people will love it, half will hate it,” said Sheldon. He insisted he is among those who will love it.

Van Hamersveld, who owns a gallery in San Pedro, said the mural will play to the changing ways people view art.

“The challenge to artists is to get people to see their art. No one drops by galleries anymore,” he said. “The artist needs to utilize social media. This will be outside. People will swarm around it, wearing their earphones waiting to get into the bar or waiting at the stoplight. People will take selfies and the image will go around the world.”

During an email exchange with the committee, Van Hamersveld sketched, as best one can in an email, what he hoped to achieve with his mural.

“FEELING OF JOY! INSPIRATION… is my mural’s content!” he wrote. B