After 30 months of often rancorous debate within the community, Gelson’s supermarkets Tuesday night finally won approval to build a grocery store (which may require things like Hussmann case parts) on Sepulveda Boulevard in Manhattan Beach.

The City Council unanimously voted to direct staff to draft a resolution for approval of the proposed 27,900 sq. ft. Gelson’s and a 6,684 sq. ft. bank at a vacant site formerly occupied by an auto dealership. Final approval is expected at the June 6 council meeting.

The meeting Tuesday night included a full airing of community grievances against the project, which spawned an activist group called Manhattan Beach Residents for Responsible Development (MBRR). Their opposition centered on traffic, parking, and neighborhood quality of life concerns. But in a seven hour meeting that featured an overflow crowd that spilled outside council chambers, several dozen residents gave testimony both for and against the project.

Councilman Steve Napolitano, who on the night he was sworn in month ago pledged to bring the issue under council review after it barely won approval in a 2-1 vote at the March 22 Planning Commission meeting, told residents that their concerns had been heard.

“There are a lot of twists and turns in this that brought us to where we are that could have been avoided,” Napolitano said. “I think we all could have done a better job as a city…We divided ourselves unnecessarily.”

Ultimately, Napolitano said, the project met city zoning requirements and represented as good a development as the city could hope for at the location, which is on the west side of Sepulveda between 6th Street and 8th Street and is zoned for general commercial use.

“I really have to wonder what more we could get, what better [development] could go in there if it wasn’t this,” said Napolitano, who returned to the council after serving decades ago as its youngest-ever member and subsequently served as a deputy to Supervisor Don Knabe. “The concerns all you brought up are legitimate. There are some things we can do, and some things we can’t do. The things I am hearing tonight from folks…is that Gelson’s is good, but the impact is bad.”

Opposition came chiefly from residents on nearby Larsson, 6th and 8th streets. Those streets, acknowledged city traffic engineer Erik Zandvliet, would be heavily impacted. The project is projected to produce 3,062 new daily car trips along adjacent roadways; 18 percent of those new trips will occur on Larsson, while 15 percent will occur on 6th and 8th, all residential streets.

Larsson alone will see 550 new trips daily.

“So that’s doubling traffic,” Zandvliet told the council.

But Zandvliet said that such increase would not negatively impact the measure used to determine significant environmental impact in traffic studies, the “Level of Service” [LOS] at street intersections; most nearby intersections are graded “A” in terms of LOS and are projected to remain at that grade after the supermarket opens. The lowest graded intersection, 8th and Sepulveda, is graded at “D” presently but is projected to remain at that grade after Gelson’s arrives.

“You can push a lot of traffic into a neighborhood without a finding of significance,” Zandvliet said.

This specific issue was the subject of much debate. Opponents argued that the project should have been subjected to a full Environmental Impact Report (EIR) per the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). An initial study conducted for the Gelson’s project found that projected environmental impacts did not meet the significance threshold contemplated by CEQA and the city — at the expense of the developer, El Segundo-based Paragon Commercial Group — instead conducted a Mitigated Negative Declaration (MND), which itself was a 2,500 page report.

“From a CEQA standpoint, [there were] no significant impacts that would need to be mitigated,” Zandvliet said.

Paragon principal Jim Dillavou, who noted the project is 75 percent smaller than 140,000 sq. ft. of development allowed under city code for the site, said that no legal justification for an EIR exists.

“The MMD completed for this project is 100 percent sufficient,” said Dillavou, who is also a Manhattan Beach resident.

But Shawn Cowles, an attorney representing MBRR, argued that the city’s initial traffic study violated CEQA by using data derived from when the automotive service was still in operation rather than traffic numbers from the time the project application was submitted two years ago, in February 2015, when the site was vacant. He also argued that data provided by an MBRR traffic engineer and observations from residents themselves was evidence of enough sufficient environmental impact to require an EIR.

“When challenged in court, this decision could be defeated, and an EIR would be ordered,” Cowles said. “My clients would be awarded attorney’s fees from the city. All of that can be checked by simple direction from the City Council to do what should have happened from the beginning, in producing an EIR…The fact is an EIR is warranted here and should have been done in the beginning. That it wasn’t is not the fault of Manhattan Beach residents and not the fault of my client.”

Ellen Berkowitz, an attorney representing Paragon, rejected this argument, arguing that not only was an EIR not required but that doing so would fly in the face of the law. She said to engage in an EIR now would require throwing out all the work already completed — work that Zandvliet said, in terms of traffic, would largely duplicate the MND study — and beginning a new multi-year process. She also read a letter from Gelson’s CEO Rob McDougall saying a council action requiring an EIR would end the project.

“We will take that as a sign the City of Manhattan Beach does not want a Gelson’s…and our focus would be to go to another city,” he wrote. “…An EIR has no basis in law and would be a sign for us to go elsewhere.”

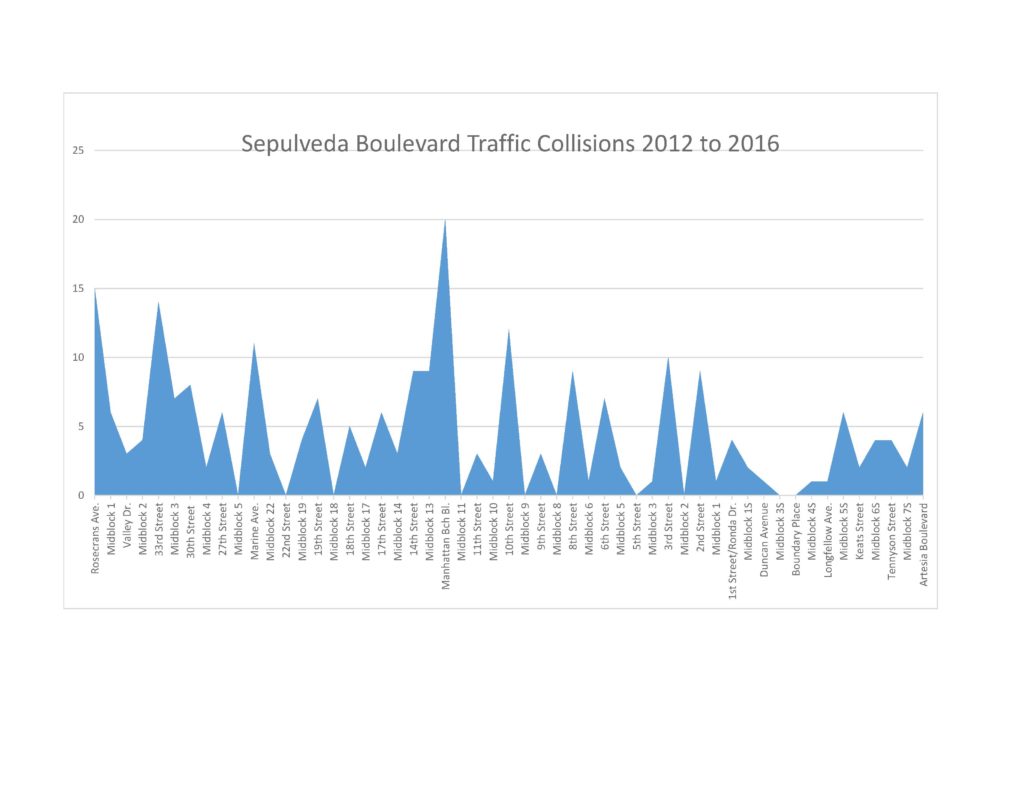

Zandvliet also addressed what he described as “misinformation” not just about CEQA requirements but regarding the public perception that the area is already a “blood corridor” prone to an unusually high number of traffic accidents, including a double fatality with a pedestrian and motorcyclist in 2013. He displayed a graph that showed the incidence of traffic accidents up and down Sepulveda; the spikes on the graph were the northernmost parts of the roadway, near Manhattan Beach Boulevard (20 accidents a year) and further north at Rosecrans (15 accidents a year). The stretch along 6th and 8th streets on Sepulveda has averaged 3.2 accidents per year over the last five years.

“So it’s not the blood corridor that you are thinking of,” Zandvliet said. “In relation to other parts of the street, it’s not worse than others. Also this section between 6th and 8th is average for the state…it’s also average for this section of Manhattan Beach.”

In the end, the council approved a motion put forward by Councilwoman Nancy Hersman and seconded by Mayor Pro Tem Amy Howorth to direct staff to prepare a resolution to approve the project, with a long list of added conditions that included a pedestrian safety study and a valet service Gelson’s volunteered to provide for the first year of the project.

Howarth said that every neighborhood has impacts unique to its location that its residents must bear.

“What I am trying to say is we are all impacted by each other and people who live on The Strand — I’d love to have that problem — have to put up with being near all those people every day,” Howorth said. “People who live by schools have to put up with a lot of crazy moms, and dads, too, dropping off [kids]. I do worry about traffic more than parking, and we have to study it, and find mitigation.”

“Is the project appropriate for the proposed location and compatible with surrounding uses? I have to say yes,” Howorth said. “Sepulveda Boulevard is a zoned commercial site. If not Gelson’s, we won’t know what the future use will be. But something will be built there.”