by Mark McDermott

In 1990, Manhattan Beach was still a scruffy yet beautiful little beach town. But it was also rapidly changing in a manner that threatened to leave its middle class roots behind. Strand lot prices hit $1 million, and other signs of gentrification were arriving, including high-end shops and a proliferation of real estate offices. A community that had prided itself as a sleepy little town where everybody knew each other was experiencing a wave of teardowns and a turnover in homes, businesses, and people the likes of which it had never seen before.

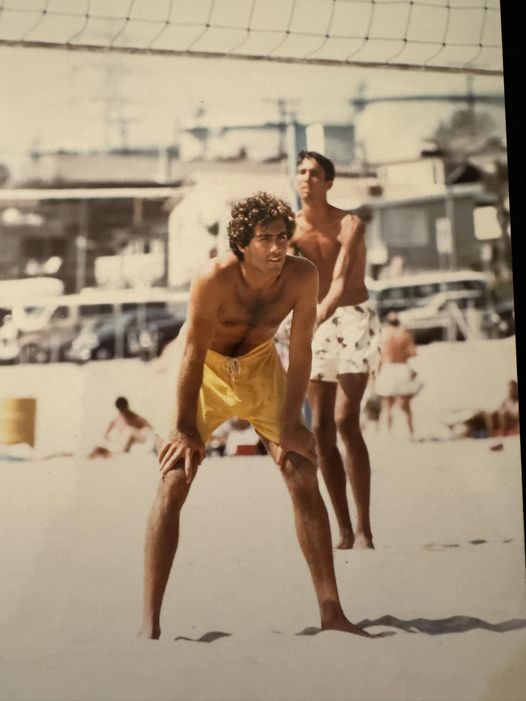

Steve Napolitano was 24 years old and Manhattan Beach was his hometown. He’d grown up playing beach volleyball, bicycling on The Strand, and, when he was old enough, finishing long sunny days drinking beers and eating burgers with his buddies at Ercoles. He also knew how lucky he was to call such a place his home, and had no intention of ever leaving. He was going to college nearby at Loyola Marymount, working as a janitor, and paying close attention to what was happening in his town.

“Manhattan Beach was in the middle of a huge zoning revision, and I didn’t think enough was being done to preserve our small town atmosphere and low profile development,” Napolitano recalled. “Things that concern every 24 year old college senior, right?”

He picked up a Beach Reporter one day and happened upon a notice that it was the last day to turn in signatures for prospective council candidates. Two incumbents and one challenger were running, so Napolitano didn’t see the current trajectory changing. He didn’t believe there was enough of a sense of urgency to protect the town’s essential character.

“So I went down to City Hall and pulled my papers at 3 p.m.,” he recalled. “I went around my neighborhood to get the minimum 20 signatures and turned them in right at 5 p.m.”

It turned out that a woman who’d lived across the street from Napolitano all his life was actually a Canadian national, so her signature didn’t count. His nomination papers were invalidated.

“That left me with the decision to wait two years to run again, or run as a write-in candidate, which was nearly impossible to win,” Napolitano said. “Like most everything else I do, I chose the hard way and ran as a write-in candidate because I figured the City wanted change sooner rather than later.”

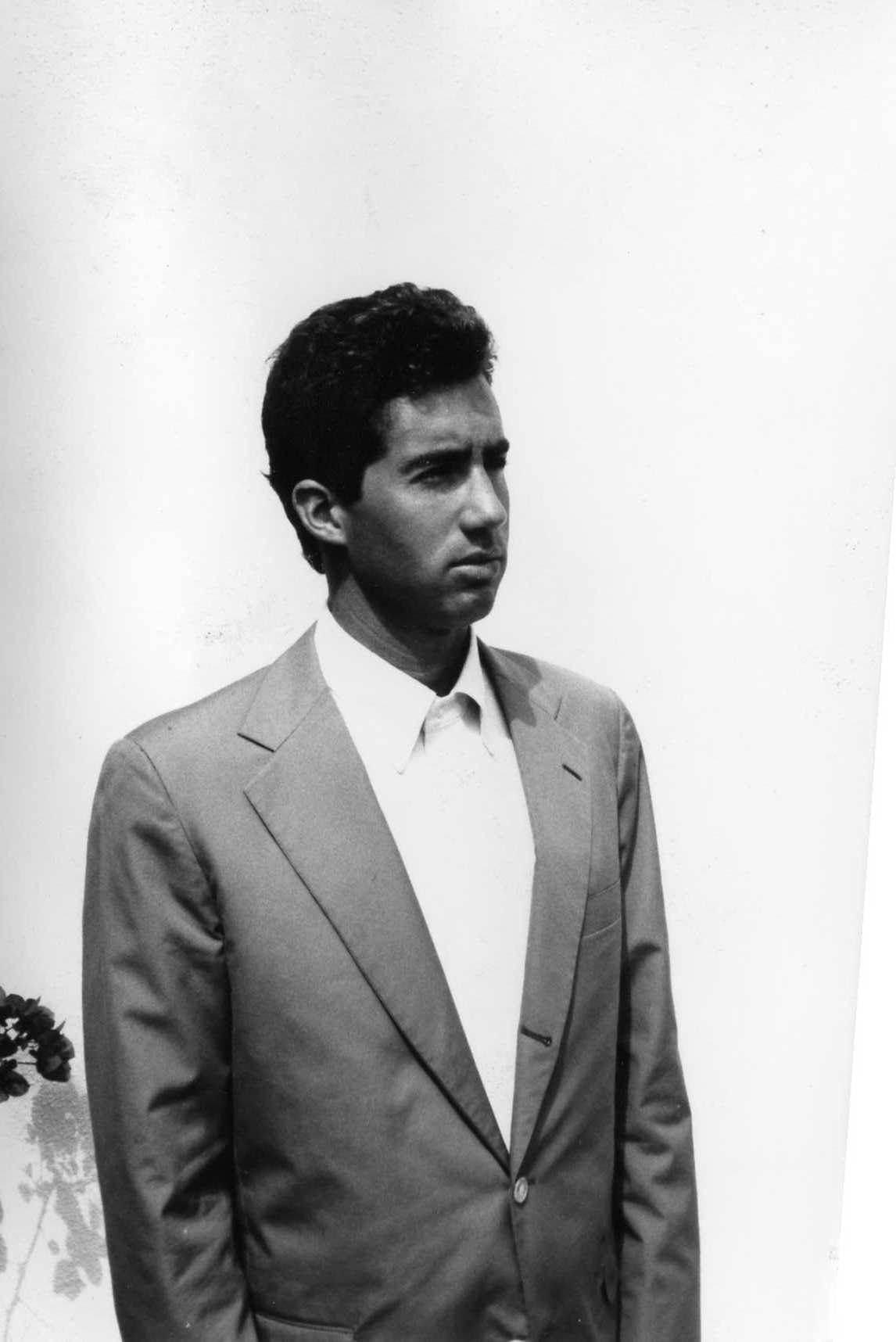

So began Napolitano’s quixotic first run for political office. He was among the more unlikely candidates in local municipal history. He didn’t even own a suit, and wore flip flops more often than shoes. He was bushy haired and tan and tended to have a sheepish grin on his face. He had almost no money, so he and his lifelong buddy Charlie Cangialosi printed some black and white campaign flyers and hit the streets, knocking on doors.

“No [voting propensity data] or list of voters, we couldn’t afford that,” he said. “We went to every door in the city and apparently nobody had done that before, or so we were told.”

At first, few took his candidacy seriously. But he just kept knocking on doors, and little by little, Napolitano’s name began spreading throughout the community.

“We started getting enough traction that the papers couldn’t ignore us anymore, so they included me in their question and answer, put my picture in the paper and I started getting invited to candidate forums where I was so out of place I read off a clipboard.”

If most of the community was surprised, at least one person was not. Dealea Aldrich is best known as a legendary coach who brought state titles to the Mira Costa High School girl’s volleyball teams. She was also a physical education teacher and a counselor at the school. She and Napolitano had formed a bond during his student days. She saw something special in him.

“He was energetic. He was friendly. He was kind,” Aldrich recalled. “He had a bundle of friends. He mixed with everybody — I mean, I don’t know a person who did not like him. He did his best in school. He was a child who kind of had a path, so to speak. He was very much interested in history. He was just an all around good person. He always had a smile. He listened and asked questions. He was kind of a born leader.”

When Aldrich saw that he was running for City Council, she couldn’t help but smile. Napolitano looked much the same as had as a teenage kid at Costa, but something about his run for elected office just seemed right.

“He was a baby,” she said. “I grinned, and just laughed, and thought, ‘Oh my god, this is amazing. But I was not surprised.”

Napolitano lost the election, but ran surprisingly strong, finishing 150 votes behind the incumbent mayor. It would be the last council election he’d ever lose. He ran again two years later and won, with the most votes, then won reelection in 1996 and 2000. He left to become a deputy for LA County Supervisor Don Knabe in 2004, then returned in 2017 to serve two more terms. Every time he ran, Napolitano received more votes than anyone else on the ballot, and each time, he received more votes than he had the previous time. Napolitano served as mayor a record six times — it’s a rotational position among the council — but in a sense he became the perpetual mayor of Manhattan Beach.

Nobody’s voice has been listened to more closely on more issues for the better part of three decades, and nobody’s lead has been followed as much as Napolitano’s. He has put in his 10,000 hours, and then some, as a public servant and local leader, and has achieved a mastery unmatched in recent South Bay political history.

Mayor Pro Tem Amy Howorth, who has known Napolitano more than 20 years, going back to when she was an MBUSD school board trustee, said she has never known an elected official better suited for the job.

“It is a true calling for him to be a public servant, really, more so than anyone else I’ve met,” Howorth said. “He looks at it as a privilege that he gets to impact this community that he loves so much. He’s patient with people, and he’s kind with people, mostly. It’s easy to say, ‘Well, Steve loves Manhattan Beach,’ but he would be this way no matter where he was living, no matter what it was. It’s just a calling.”

Napolitano terms out at the end of this year. As he exits the political stage, he is aspiring to become a different type of public servant altogether. He earned his law degree from Loyola Marymount in 2000, in the midst of his earlier political career, serving as a public school teacher as he worked his way through law school. He began his legal career representing school districts, and in recent years has become a state appointed attorney for inmates seeking parole, as well as an administrative law hearing officer for cities and counties regarding code violations. Last year, as the end of his council term approached, he began thinking about how he could put his unusual combination of experience to best use.

“I’ve never been one to plan much in terms of career paths,” Napolitano said. “I reflected on the fact that I had all this experience in different things — in dealing with controversial subjects in public policy, in legislation, in dealing with issues of crime, housing, homelessness and so much more on my political side, and then I had all this experience on my legal side, as someone who has worked with both criminals and victims, in knowing the causes of crime and how to turn people away from it, in acting as a decisionmaker over cases with penalties ranging from $250 to over $1.5 million. And I thought to myself, how can I bring all this experience together in one job for a change instead of doing four or five at the same time? And I kept coming back to judge.”

He did his due diligence, talking to judges and some other attorneys he knew. They all encouraged him to run. And then earlier this year, Napolitano pulled his papers. Once again, he felt a calling.

The race for the bench

Napolitano is running to become Judge for the Superior Court of Los Angeles Seat 39. This campaign is certainly not quite as quixotic as his first council run, but it is similarly unconventional. Superior Court candidates tend to come from the criminal justice system — deputy district attorneys and public defenders, or private attorneys who have spent careers in courtrooms.

In February, prior to the March primary in which Napolitano faced four other candidates, he said that the fact that he is not a traditional candidate is part of why he chose to run.

“Being a judge is about more than just the law, it’s about life and how experience informs decisions,” he said. “That’s the choice here — what makes a better judge? Someone whose experience is informed by basically doing one thing, or someone whose experience is informed by doing many things?”

He said that his 30 years in the public sphere have been a study in pragmatic decision making.

“I’m tough but fair, and I want to make the law work for all of us,” he said. “I believe in consequences. I also believe in compassion. I believe we need more judges with diverse backgrounds who know our communities, who have worked with both victims and criminals, and who have the experience to know what works and what doesn’t. That’s who I am, and that’s why I’m running for judge.”

Napolitano had little idea how his qualifications would be regarded by “the legal establishment,” which holds considerable sway in such elections.

“There tends to be a bias towards prosecutors or public defenders, which seems silly given that judges can be assigned to civil court, family law court, juvenile court, CARE courts, etc.,” he said. “There’s a lot more than just criminal cases that judges oversee, but again, there’s not a lot of information out there for people to make informed choices. I call the judicial races the ‘flyover´ part of the ballot for a lot of folks because they don’t usually know who they’re voting for and most people rely on the ballot designation, the endorsement of the LA Times and a few other sources to make their decisions.”

In the primary, once again Napolitano received the most votes, but this time on a larger scale. He earned 217,179 votes, or 30.2 percent, and will face the runner up, deputy public defender George A. Turner, in the November 5 election.

And while it might not be the legal establishment, Napolitano has garnered the backing of 75 elected officials in LA County, including three LA County Supervisors of different political persuasions, Kathryn Barger, Holly Mitchell, and Janice Hahn, the latter whom Napolitano ran unsuccessfully against after Don Knabe retired in 2016.

“They know I don’t want to be on the Supreme Court or oversee the next ‘trial of the century,’” Napolitano said. “I want to deal with nitty-gritty cases where people might be engaging with the justice system for the first time on a misdemeanor case, a small claims case, or in homeless court. I want to be able to talk to these folks. Help get them on a better path. Make a difference.”

He also earned the endorsements of the the LA County Association of Deputy Sheriffs, the LA County Lifeguards, the Association of Deputy District Attorneys, and, perhaps most influentially of all, the Los Angeles Times. The Times endorsed him for the very reason he ran, his diversity of experience.

“Varied backgrounds like Napolitano’s are valuable assets,” The Times editorial board wrote. “Attorneys who spend their entire careers as prosecutors or criminal defense lawyers typically become very good at what they do but don’t always make the best judges. Having viewed the justice system from a single window, they may have trouble making the transition to the bench, where a wider and more balanced perspective is needed.”

His longtime colleagues on the council see another quality that they believe will serve Napolitano on the bench. His temperament.

Councilperson Richard Montgomery is likewise nearing the end of a long council career, having served 16 years, the last eight with Napolitano. He said that was especially impressed with Napolitano’s ability to preside over meetings when he was mayor, and even as a councilmember inject needed doses of common sense into proceedings. And perhaps more crucially, Montgomery said that Napolitano listened to all testimony, did his own research, and never rushed to judgment.

“When he was mayor, he ran meetings like a business meeting,” Montgomery said. “He took public comments, but kept us on the agenda, and some people try to swerve off. He would bring them back to it….Steve would bring that even tempered disposition to the bench. I don’t know about you, but when I go in front of a judge, I want that judge to be fair, to listen to my whole story and not cut me off, and not prejudge. And then give his opinion based on the facts, and what you said, which is what we do on the council, right? I think that is his strength.”

Both Montgomery and Howorth said Napolitano possesses the simple but underrated ability to cut to the chase. This manifested itself in council proceedings both in the way Napolitano could reduce a complicated issue to its fundamental essence, often with a pithy statement laced with touch of dry humor, and in his penchant for crafting on-the-spot solutions or legislative compromises the likes of which often drag less focused councils through meandering discussions and delayed decisions.

“He’s got that attorney’s dry wit,” Montgomery said. “Other councilmembers would litigate the heck out of something that should take 30 seconds and make it 20 minutes, as if they were billable hours. Steve will get it to you in two minutes. ‘Look, folks, here is what is happening…’ And just give you the straight skinny, so everybody gets it. ‘Oh yeah, that makes sense.’”

Howorth said Napolitano’s broad experience, both locally and regionally, enabled him to marshall what otherwise could have been messy deliberations.

“He knew so much, not just about how to get things done locally, but who the different agencies were, and who had jurisdiction, so that he could craft solutions in real time and from the dais,” she said. “After listening to community input, after listening to his colleagues, sometimes he comes up with something different than is presented in the staff report. Sometimes he’ll say, certainly but kindly, ‘Hey, staff, you’ve got to go back and bring us more.”

Napolitano said his approach is less from any kind of mastery attained over the years and more about what his parents taught him.

“Do your homework, listen, ask tough questions, act with integrity at all times and treat people fairly and with kindness and respect,” he said. “That’s what my parents taught me, and that’s what I’m teaching my own children.”

Everybody’s brother

Whatever the outcome is on November 5, when Napolitano leaves the council it will mark the end of an era.

His legacy with the city has too many layers to enumerate. Early on, he was an effective brake on overdevelopment, successfully championing open space requirements for new projects that helped tamp down — or in some cases, ward off — some of the more blindly avaricious developments. He also helped attach public art funding to developer fees, which planted the seeds for the artwork that now permeates the city. Perhaps most significantly, in matters of overdevelopment, is that Napolitano was the lone voice on the Council opposing an earlier, much larger proposed iteration of the Metlox project. But his opposition was soon joined by a grassroots movement whose rallying cry was “Small town Downtown,” and the council was forced to reverse itself.

City governance is many-fangled, and matters that seem small often have an incremental effect towards the larger goal of protecting a city’s character. For example, Napolitano backed the waiving of City fee waivers for cherished local events, such as the Hometown Fair, the MB 10k, and the Pumpkin Race, helping ensure that they go on by providing a little bit of help. In another matter, back in 1996, the Council created the Beach Volleyball Walk of Fame. Napolitano successfully argued for something that was not a given at the time — the inclusion of women.

“He did that when he was a much younger man and it was not at all popular to do it,” Howorth said.

His final eight years on the council have been a master course in effective governance. He and Montgomery rejoined the council together with a shared motto, “To get things done.” That began with cutting off the head of the snake, a rogue city manager, Mark Danaj, whom they let go without cause, which meant he collected his hefty salary for a year. It was a personnel decision, and thus confidential, so residents had no idea why the decision was made. Danaj was later indicted in another city for embezzlement. Meanwhile, Manhattan Beach hired a trusted old City Hall hand, finance director Bruce Moe, and began the process of setting things financially right. Much of what has happened since is of the decidedly, workaday sort, unsexy but essential — a new water reservoir, a new Fire Station #2, the passage of a stormwater fee to stop the bleeding from the General Fund, and the proposed half-cent sales tax that would provide revenue and potential bonding power for a long list of infrastructure needs.

He also fought off an attempt to rename Sepulveda Boulevard to what it is called in other cities, Pacific Coast Highway, something Montgomery argued for, and still keeps in his craw, but reluctantly respects.

“He’s a calming presence on council,” Montgomery said. “Remember, he’s the only one on the council who is native-born Manhattan Beach, and that carries weight with residents….That’s a huge thing for people. So he has a vested interest. Would he like to keep it more like it was here in 1959? I am sure he does, but it’s different now. He gradually lets go of the past, but not easily.”

One issue was more painfully rooted in the past, and far from workaday. The history of Bruce’s Beach, in which racially motivated city leaders in the 1920s used eminent domain to take a Black-owned resort and surrounding properties from Black families, in 2020 attracted national attention to Manhattan Beach, and not in a good way. That history came to light during the Black Lives Matter movement and its local parallel, the Justice for Bruce’s Beach movement.

The council appointed a task force to compile an accurate history, and LA County, in an historic act of reparations, eventually agreed to compensate the Bruce family for the portion of that property it now controlled. The council eventually issued a statement “acknowledging and condemning” what the City had done a century ago, but stopped short of an apology. Napolitano did not.

In an emotional ceremony held in March 2023 for the unveiling of a new plaque that contained a short but historically accurate account of what occurred at that land, which is now a City park, Napolitano apologized.

The way he did was also an act of preservation for the character of his hometown.

“Manhattan Beach is unequivocally not a racist city in any way, shape or form. That doesn’t mean racist things can’t happen here. Anyone can say or do something racist,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean the city or its residents are racist… We are a welcoming, loving, inclusive community that has stood together, time and again, to mourn tragedies and stand up and speak out against hate, injustice and intolerance.”

“We don’t teach our children to acknowledge and condemn the things they do wrong,” he said. “We teach them to say they’re sorry…I’ve yet to hear a good reason not to do it.”

“I’ve heard all the excuses — the families were compensated, it was a long time ago, an apology is an admission of guilt, an apology will mean lawsuits. Nonsense, all of them,” he said. “I can apologize on my own, and I do. I personally apologize to the Bruces, the Prioleaus, the Pattersons, the Sanders, the Johnsons, the McCaskills, the Irvins, and the Slaughters, for the wrongful, racially motivated taking of their property by this city nearly 100 years ago. That wasn’t hard, folks.”

A few months later, the Council joined in, issuing a formal apology to the families. It was a perhaps small gesture, but one that carried meaning for many. His leadership on the issue was cited in the LA Times endorsement of his candidacy for Superior Court judge.

Howorth marveled at how Napolitano gave the apology not from some ideological or politically considered point of view, but in an almost neighborly, common sense way, less a scalding indictment than a message of enduring goodwill.

“Look at how he brought that forward and reframed it,” she said. “He made an apology without making it about how terrible people were in the past.”

At the heart of it was a quality Aldrich had identified in Napolitano more than 40 years ago at Mira Costa.

“I think he has an ability to weigh all sides of things,” she said. “That’s why I think he did such a great job all the way through his political career. He was able to have a good vision of people who were unlike him, but had a heart for their situation. In politics, or in any kind of realm of leadership, you would hope we would find that kind of humanity…I’m so happy he’s pursuing what he loves, and that’s leadership, working and helping people.”

Howorth notices something whenever she is somewhere out and about in Manhattan Beach with Napolitano.

“He runs into people he grew up with, or he runs into somebody he knows, and it strikes me that everybody thinks Steve is their brother,” she said. “He treats everybody like he’s their brother. He treats me like a brother — technically, a younger brother, but you know what I mean. Everybody, if they know him, that’s how they feel about him. He’s everybody’s brother.”

What I learned

Asked to reflect on his five terms as a councilperson and mayor, Steve Napolitano offered up the “top 10” things he learned.

1. Never forget whom you work for — the people. The residents are at the top of the organization chart here in Manhattan Beach. I owe them my duty, dedication and integrity. It’s for them that I get things done. I’m nothing, they’re everything.

2. Do your homework. That means more than just reading the staff reports. Go out and look at things. Talk to people. Go to conferences, learn from others. Talk to staff.

3. Look ahead. Don’t just get stuck on the here and now, but don’t go spending a lot of money on consultants to come up with some strategic plan that’s just going to sit on a shelf. Make decisions for the long term, especially financial decisions. Stop kicking the can down the road. Address problems now so they don’t become bigger problems later.

4. Listen to the people. It’s not enough to just work for the people. We’re blessed with some very smart, talented people in Manhattan Beach who will tell us when we’re headed in the wrong direction.

5. Question everything. I’m a natural skeptic and I think that’s a good thing. Questioning proposed projects, plans and ordinances make for better outcomes.

6. Don’t take it personally. That can be tough to do, but it’s important to remember. You need a thick skin in this business. I’ve been called so many things I can’t remember them all, but I try to understand where it’s coming from and why.

7. Explain yourself. Yes, sometimes things are obvious but sometimes they aren’t. When the issue is controversial, it’s important to explain your reasoning to folks. Even if people don’t agree, they will appreciate the fact that you’re doing what you believe is right if you can explain why you’re doing it.

8. Don’t over plan. Fifty percent of this job is stuff that’s planned, fifty percent is stuff you never planned, and fifty percent more is dealing with unintended consequences. Yes, that’s 150%, but it’s true. Be flexible and try to imagine every consequence possible before making a decision.

9. Trust but verify. We have a great staff and they do great work, but that doesn’t mean they get a free pass or a blank check. Appreciate what they do while holding them accountable at the same time.

10. Have fun. Local politics is where things really happen. It has a bigger effect on people’s lives on a daily basis than any other form of government. It also means people know where you live and have no problem stopping you at the store to talk politics. That’s all part of it, and I love it. The people’s work is serious work, but you gotta have fun doing it.

I am extremely blessed to have been entrusted to serve my community in one way or another over the past 32-plus years, and I’ll continue to serve it one way or another for the rest of my life. It’s been my honor and privilege to serve my hometown and LA County, and I hope I’ve made a difference, because that’s all I’ve ever wanted to do.