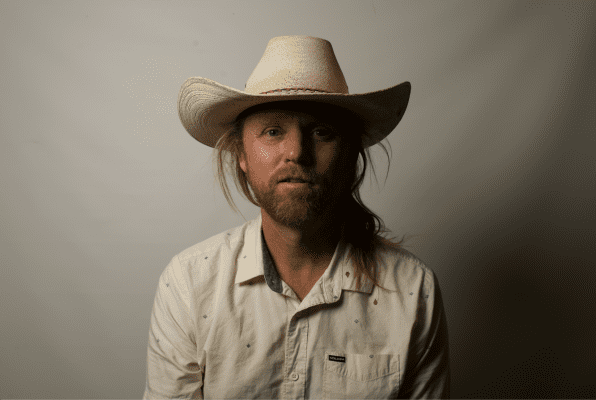

When Eric Pendergraft came to Redondo Beach in 2006, he had no idea that he’d have to learn how to run political campaigns, or rehabilitate tenuous relationships with public entities. He was just an engineer who liked power plants.

But now, just shy of a decade of near-constant conflict, it seems that peace is almost at hand.

“I’ve spent so much time in this community,” he said. “I’ve vested myself in what we’re doing, and now I’ve got a strong personal interest in making this successful. I mean, every time I drive down 190th Street, I just imagine what could be.”

“What could be” is the opportunity to replace the AES Redondo Generating Station — the power plant that’s been a part of Redondo’s waterfront landscape and consciousness for more than 100 years — with a mixed-use residential and hotel development called “Harbor Village” that would provide Redondo Beach with what supporters call “the Crown Jewel of the South Bay.” That’s if Measure B, a rezoning effort brought forth by AES last summer, wins a majority of the ballots in the March 3 election.

Standing in B’s path, however, are passionate Redondo locals, suspicious of the power company’s motives and distrustful of the city’s waterfront redevelopment plan. They seek to stop Measure B and, instead, put forth a ballot measure of their own written by the people of Redondo Beach, for the people of Redondo Beach.

“It’s a farce; it’s a corruption of the initiative process,” said Jim Light, a community activist and head of Building a Better Redondo. “To let the property owner zone their own property — nowhere else in the state can you do this.”

However, a defeat of the ballot measure may come at the cost of further stalling an issue that’s already taken decades to develop and — according to Measure B supporters — potentially derail the city’s opportunity to be rid of the plant, once and for all.

“Measure B is the only way to guarantee the removal of the power plant,” said Redondo Beach Mayor Steve Aspel. “It will provide absolute certainty that we will have a waterfront free of the power plant and all industrial development.”

How we got here

The city has been fighting over the fate of the AES power plant since the turn of the millennium. Aspel calls it the most divisive issue he’s seen in the two decades he’s been involved with the city.

“I can’t count how much time, energy and money has been spent on this issue,” he said. “It’s created enemies within the community. Some people who were friends before may now be enemies.”

The debate traces back to the Heart of the City plan in 2001, when Aspel was a member of the city’s planning commission. The plan would have called for a massive overhaul of the city’s waterfront area, adding 360,000 square feet of restaurants and retail alongside 700,000 square feet of office space. The crux of the issue, however, was the 2,998 residential units zoned at the AES site as part of the area’s development.

The city rescinded the proposal after Redondo’s residents, led by Chris Cagle, gathered more than 6,000 signatures in an effort to force the plan onto a ballot.

Further warring over development led to the passage in 2008 of Measure DD, a 10-page amendment to the City Charter written by a citizens group called Building a Better Redondo that requires a vote on “major changes to allowable land use” in the city. Those “major changes” include the conversion of public land to private land and any proposed conversion of non-residential to residential zoning of at least 8.8 units an acre. The initiative was passed by 58 percent of the city’s electorate.

The city’s battle with AES continued into 2009, when the campaign for Measure UU, which would have rescinded the power plant’s Users Utility Tax exemption, drove a deeper wedge between AES and the City of Redondo Beach. A fiercely contested election eventually saw the power company come out on top, as a mailing campaign secured a majority from the city’s absentee voters, which more than made the difference in the late 2009 election. Then-Councilman Aspel bitterly accepted the results, saying that AES had ruined its relationship with the city.

“Unfortunately, people who voted by absentee ballots were voting based on fear and not the truth,” Aspel said in 2009. “I firmly believe people were duped by AES. And I will reiterate: our relationship with AES is forever tainted. … There is not going to be any love between us at all.”

That made it all the more shocking when Aspel and AES Southland president Eric Pendergraft buried the hatchet over the Harbor Village proposal.

As Pendergraft said last August, “The city gets what they want: additional revenue and a brand new, revitalized waterfront without a power plant. The community gets a great place to visit, enhanced views and higher property values. We get a fair value in return, and those folks who have concerns about a new power plant, those concerns are alleviated because there won’t be one.”

Now, after years of struggle, AES and the City of Redondo Beach seem to be on the same page, as the City Council lent its support to AES’ Harbor Village plan in a 3-2 vote on a resolution made to encourage AES to suspend its application for a new power plant.

The Council’s dissenting votes came from District 4’s Steve Sammarco and District 2’s Bill Brand, an outspoken opponent of AES for more than a decade.

A broken engine

From his beginnings on the City Council, Brand has made it part of his mission to reclaim AES’s land for Redondo’s greater good.

Shortly after he was elected to city council, Brand dedicated himself to learning as much as he could about the energy industry in order to, as he said, “get my head around whether or not we would need the Redondo Generating Plant in the future.”

The answer, he says, is “absolutely not.” His research revealed that there was sufficient energy capacity in the region to permanently retire a large, once-through cooling power plant (meaning a plant that cycles ocean water through to cool its generators). “I took those as my marching orders,” said Brand, who made it his mission to rezone AES’s land for something that maximizes open space while remaining economically viable.

Brand co-founded the South Bay Parkland Conservancy with this in mind.

“Redondo is something they call ‘park poor,’” Brand said.

According to a study done by the USC Center for Sustainable Studies, Redondo Beach has 2.45 acres of parkland for every 1,000 residents – a figure that includes the beaches, school property and the land under the power lines. That puts it in the same “park poor” category as East LA and South LA, areas that have a severe deficiency in parkland.

The ten acres of open space set aside in the Harbor Village plan don’t cut it, Jim Light says. Light, a community activist, longtime ally of Brand, and founder of Building a Better Redondo, argues that the “open space” definition within Measure B is too loose, allowing for medians, sidewalks and drainage ditches to be considered “open space.”

“What’re you going to do, send your kids out to play in a drainage ditch? That’s ridiculous. It’s not usable by the public,” Light said. “That would never count in any development in Redondo; it’s a terrible precedent to set.”

Light’s analysis of the Harbor Village plan finds a significant issue with the proposed number of housing units: Namely, that the 600 units could balloon given California Coastal Commission involvement. State law awards a“density bonus” for affordable housing in multi-family zoned areas with more than five units, allowing for a potential of 724 total residential units on the property. That could push the height of the development to 60 feet, or three-quarters of the Wyland Whaling Wall, Light argues.

That development, according to Brand, is also a financial loser for Redondo Beach. Taking figures from a Net Fiscal Impact report commissioned by AES, Brand says that the project would raise $1.57 million annually for Redondo’s general fund.

“We get more money from parking revenue at our structure on the pier,” he said. “That’s a pittance. That’s almost a rounding error.”

Both Brand and Light argue that infrastructure and city service costs associated with large-scale residential development outweigh the revenues it would generate . With a back-of-the-envelope calculation, Brand worked out that a 250 room hotel by the waterfront, charging $250 a night with an average of 80 percent occupancy, would generate $2.2 million dollars for Redondo Beach annually – in Transit Occupancy Tax alone. “Never mind sales tax or property tax from the hotel,” he said. “The net of the entire Harbor Village plan, including a 250 room hotel, is less than that. How is that possible? Because they put in so much residential that it drains away from the hotel. Their entire project is predicated on the success of that hotel.”

The potential for major traffic problems also draws the ire of opponents to Measure B. According to Light’s calculations, based on figures from the Institute of Transportation Engineers Trip Generation Tables, Harbor Village would create 11,269 weekday trips and 12,391 weekend trips. To put that in perspective, Pacific Coast Highway at 190th Street has 40,000 trips on it each day, while Catalina Avenue has 16,000 trips daily, Light said.

Light and Brand say that combined with the “Waterfront Project” commercial development proposed by CenterCal in King Harbor — 290,000 sq. ft. of new development — would create a nightmare of overdevelopment.

“AES hasn’t done a traffic analysis that they’ve shown us, CenterCal hasn’t done a traffic analysis that they’ve shown us,” Brand said. “But it’s not hard to figure out if you double the development on King Harbor, add 600 homes at the AES site and a hotel, plus 85,000 square feet of commercial to an area that’s already saturated on traffic, it’s going to cause gridlock, regardless of what anyone says about mitigation. You can’t mitigate the traffic impact that these two projects [CenterCal and Harbor Village] are going to bring to Pacific Coast Highway.”

The solution, Brand says, is simple – and it starts with defeating Measure B. “You vote down B, you bring the community together and you do meaningful engagement of the community.”

In the minds of those opposed to B and the CenterCal waterfront redevelopment project, the issue is a lack of comprehensive waterfront reform — to try and separate the ballot measure and CenterCal’s proposal, which opponents have called a mall on the waterfront, is a mistake.

“What’re we going to leave for future generations? Are we going to do a piecemeal, rush job? Or are we going to do it right? The reason Redondo Beach has done all of this start-stop development is that leadership keeps bringing big development plans to the community that they just don’t support. Residents have failed to put people in power that will bring real leadership who will work to get what they want to see in their waterfront.”

“Citizens should force AES to work with the community on reasonable rezoning that minimizes the impact on the city and that provides them with a fair return on investment,” Brand said. “They basically abused what is a citizen’s initiative process to get what they want.”

What Light proposes, should B pass, is a wait-and-see approach that depends on the makeup of the council – ideally hoping that an anti-B council candidate such as Candace Allen Nafissi would win her election and take actions that would throttle back or pause development along the waterfront.

“We also have draft zoning ready to roll out for the whole waterfront that keeps the harbor a harbor and balances the uses so it’s actually a boon to the area,” Light said. “Our design would have very low amounts of residential zoning, and would be an incentive to make the whole area beautiful, not just the AES property.”

In his opinion, it’s not that the harbor is under-developed, it’s that it doesn’t pull enough customers on a daily basis.

“Our plan is to put development on the AES site that draws [visiting] professionals to work in that area. They fly in, buoy up the hotel usage, and when they go to lunch, they walk across the street to get some food. It draws people to the harbor without having to overbuild the harbor.”

“We need to stop this stupid process now, not later,” Brand said. “Not try to fix an engine that doesn’t run in the first place.”

A chance to move on

In Aspel’s mind, there’s no question behind the reason for his support: Measure B the only way assured to get rid of the power plant.

“There might be other ways,” he said, “but they’re not guaranteed.”

“Whether people believe it or not, AES has the right to rebuild another power plant,” he said, contending with Brand and Light’s supposition that AES has no recourse for their land if B fails.

“If this loses, [AES] is going to go back to the drawing board, and we will be back fighting. This is just a guaranteed way to get rid of it. If it wins, then we’ll know in 2020 they will cease operation, and they’ll start dismantling it, and they’re going to have to come up with a plan then. This is only a zoning initiative.”

That “only a zoning initiative” thinking plays largely into Aspel’s position: At this point, he just wants the plant gone.

“I’m tired of dealing with the power plant, ” he said.

It’s also an extremely rare situation, Aspel argues, in that Pendergraft and AES are willing to cooperate with the city’s wishes to rid itself of the power plant.

“They’re willing to go away. They’re not stupid,” Aspel said. “I met with the president of the company back in Virginia and Pendergraft here and they’re just tired of the hassle. They answer to stockholders, and they’re not a human being, they’re a corporation. It’s all about the bottom line. Their experts came up with that zoning to make their profit and go away.”

Aspel isn’t concerned with what the final product will look like at this stage in the process, recognizing that the proposed drawings offered by the Harbor Village plan are just that: A proposal.

“With zoning, you know the maximum, that’s all. I’m not in charge of the design. That will go through hundreds of iterations. That’s the next step. You can’t do it all in one day,” he said. “I would be shocked if there were shovels in the dirt to build new houses or hotels in even six years.”

“This is the maximum zoning allowed — maximum density,” he continued. “By the time they come up with plans, there will probably be a new mayor, council, and commissioners. They will have to negotiate for services, infrastructure, for the amount of units, etc. That’s for us to figure out six or seven years from now.”

“We had a supporter event recently,” Pendergraft said. “What I led off with is ‘If you remember nothing else, Measure B provides certainty that the existing power plant will be removed and there will be no further industrial development on that site. That guarantee disappears if Measure B fails. There will be plenty of time to talk about and debate and discuss what the actual project is going to be…but if you want the power plant to go away, vote yes.”

As Aspel and Pendergraft have repeated numerous times throughout this campaign season, that’s what they feel Measure B is really about — getting this piece of legislation passed so they, and the rest of the city, can move on. But for AES as a company, the only thing that matters is that they get compensated — Pendergraft is more than willing to acknowledge that, and says that Measure B could also result in a park should funding be obtained for open space.

“As long as we get paid fair value for the property, we don’t care if it’s homes or a park,” Pendergraft said.

Harbor Village, he said, wasn’t created to absolutely maximize value; it was created in part to compliment the project proposed by CenterCal — Harbor Village would provide customers for the commercial development — and with a desire to satisfy AES’s senior management with a plan that would “compare favorably to industrial alternatives.”

Those alternatives, Pendergraft said, include the construction of a new power plant, a desalination plant and even, should Measure O fail in Hermosa Beach, the potential for oil drilling on the site. But those are worst-case scenarios; options that could be pursued in the case that Measure B is defeated.

“One of my biggest concerns is that people are going to let this opportunity slip through their fingers — [the idea] that there’s something better out there if they defeat this,” Pendergraft said. “We don’t want to make this ‘Measure B or else’ kind of thing. This is being presented as a compromise, a win-win that we’re comfortable accepting, and for the city and the community to get something that’s fantastic.”

“I know what the opposition is thinking, that they’re running scared, this is a preemptive strike in case they don’t get their permit [to repower]. That could very well be,” Aspel said. “But they’ve come up with a compromise that’s a collaboration with the city and what we think the voters will go for. As long as they get it, they’re going to go quietly. If they don’t, I think Redondo Beach is going to have industrial use there for another 100 years. If they said, ‘We want to build some kind of industrial plant there’ we couldn’t legally say no. It’s their private property.”

It’s that desire for compromise that’s motivating Pendergraft.

“If there is a genuine desire by the majority of the people of Redondo to have more open space here, let’s get Measure B passed, get the industrial option off of the table, and work collaboratively to have creative ways to raise funding to have more open space. We get treated fairly, we get paid for the land, but it gets preserved as more open space instead of more homes. That’s the win-win, right? We’re working together for a common goal rather than being at odds with each other.”

Towards that end, should B pass, it would mark AES’s exit from Redondo Beach; as Pendergraft said, his company isn’t in the business of land and property development. If they get their way, they’re “in all likelihood” selling the land.

“This is a very unique piece of property and it needs a world-class developer with a track record of building world-class developments along the waterfront,” Pendergraft said.

“The vision that we have is certainly not bad development adding to ‘ReCondo Beach.’ Whatever developer is brought on needs to have a strong track record of having done fantastic developments along the coast. It’s got to be treated with that level of respect; it’s got to be something special,” Pendergraft said.

To Pendergraft, it’s an opportunity to turn the waterfront into a destination — something that people travel to other cities for now.

Legacies

“This is going to be interesting,” Aspel said, acknowledging the poor voter turnouts that go hand-in-hand with off-cycle municipal elections. “If it’s a foggy day or you have the sniffles you’re not going to go out and vote. The future of the city of Redondo Beach is probably going to be decided by around ten percent of the people.”

At this point, one could get the impression that Redondo’s power plant, and the friction caused by it, has sapped as much energy from the citizens as it has produced for them — and Aspel is ready to see it go.

“The power plant has been a huge discussion for my entire political career in Redondo,” he said. “I just want it to go away and both sides can agree that we are better off without it. If we don’t make a decision on it now, we are going to be having the same argument in 10 years, long after I’m out of office.”

“The legacy to have,” he said, “would be to leave the city without the power plant.” ER