Now that short-term rentals are officially banned in Manhattan Beach, Dana Seagars is rethinking his retirement plan. Many hundreds of other property owners in the Beach Cities are figuring out what the ban means for them, too.

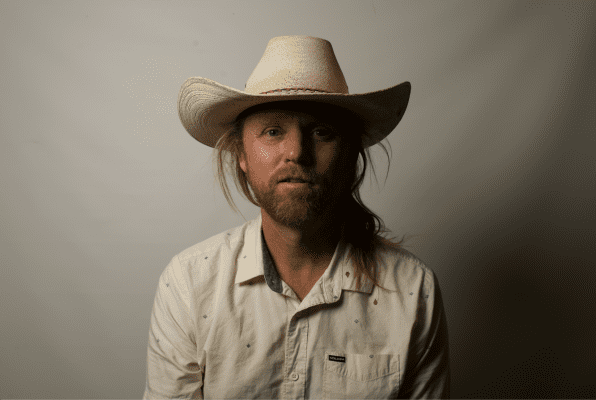

Since retiring his post as a federal marine mammal biologist in Alaska a couple years ago, Seagars has spent five months a year at an apartment in Manhattan Beach, owned by his family since 1925. To make it pencil out, he rents the unit to vacationers for most of the year while he lives in Alaska. (He also rents the two other units at the property to long-term tenants).

But following the Manhattan Beach City Council’s decision last week to ban short-term rentals, Seagars will switch the vacation rental to a longer lease. In the process he’ll lose substantial income, he said, and will likely need to take up more part-time consulting work, change his lifestyle and cut expenses. A two bedroom short-term rental that goes for $2,800 a week in peak season could rent for just $6,000 a month during the same time of the year, he said.

“Something’s going to have to give,” he said, speaking from Alaska. “I can’t come down there as much, or I will need to cut down on my living expenses, or stop making improvements to the properties. It’s probably going to be a bit of all of the above.”

Seagars had operated his vacation rental property for six years with a license from the city that allowed him and 57 other homeowners and managers to rent their houses to vacationers in town for fewer than 30 days. He listed his property on Vacation Rentals by Owners (VRBO), and worked with a property management company to market the listing. Guests paid Manhattan Beach’s 10 percent hotel bed tax, which he estimated added up to about $15,000 in taxes over the years.

Under the new law, Seagars and those other homeowners will have to end short-term rentals by the end of the year. The ban outlaws all rentals of less than 30 days.

The ban will also seek to shut down the operations of the hundreds of other property owners who have been renting to vacationers without a license from the city, often using Airbnb, which has grown into the leader in vacation rental bookings, having recently been valued at $20 billion.

A recent Airbnb search showed 473 listings in the Beach Cities. There are 447 more on VRBO, although there are some duplicative listings between the sites.

Enforcement of the ban will begin after a 30-day grace period, during which short-term rental hosts will receive a warning, said Manhattan Beach Mayor Wayne Powell. After that point, there will be some leniency for people genuinely unfamiliar with the ban. But repeat offenders will be referred to the city prosecutor and could be charged with a misdemeanor and taken to court.

“The city just wants to be fair and hopes that voluntary compliance is attained as a result of people being educated,” Powell said.

Certainly not all of the property owners affected will comply with the ban, however.

”Until I see an implementation plan from the city that is threatening to really impact me financially, I’m not going to change anything,” said one Airbnb host in Manhattan Beach, who asked not to be named so as not to draw scrutiny from neighbors or the city.

All three Beach Cities already prohibited short-term rentals in residential zones (Manhattan’s permitting system was the exception). But with just a few code enforcement officers to patrol all those neighborhoods, enforcement has always been lax.

Many people who rent to vacationers aren’t even aware that they’re violating any rules.

“Ninety percent of people in town don’t know it’s illegal,” said Hermosa Beach resident Dency Nelson. “I got on [City Manager] Tom Bakaly’s case when the city’s consultants said they were staying in an Airbnb. I said, ‘That’s illegal’ and Tom said, ‘Whoops.’ In subsequent visits, they didn’t do that.”

Short-term rental enforcement relies on citizen complaints, sometimes arising from excessive noise from partying, or renters that leave their trash in the wrong garbage bin.

But short-term rental proponents say bad behavior from a few renters shouldn’t lead to an outright ban on all properties.

“This isn’t a short-term rental problem,” Seagars said. “It’s a bad behavior problem.”

In any event, those complaints rose to a roar that was loud enough to trigger action from the Manhattan Beach City Council. At a preliminary vote on a short-term rental ban on June 2, a distressed resident said a home next door was being used as “a nightly rental for porn parties,” while other residents were concerned about parking woes and a parade of partying strangers coming into neighborhoods. Some also worried about creating a hotel-like atmosphere in a residential area.

“If people are coming in and out, that’s a really different neighborhood than I moved into and paid money for. That’s why my house cost so much money: Because this is a tight community,” Manhattan Beach Councilwoman Amy Howorth said during the council’s second deliberation on the issue last week.

Those concerns trumped economic arguments for keeping the rentals. With the ban, Manhattan Beach is turning down about $550,000 in hotel bed taxes over the next five years from the 58 licensed properties, according to estimates from city staff. There could also be a loss of money spent by vacationers at local shops and restaurants.

“Airbnb guests generate sustainable, local economic activity that supports small businesses,” Airbnb spokeswoman Alison Schumer said in a statement. “We are continuing to highlight the importance of fair rules with leaders throughout Southern California.”

Some residents, asked by Airbnb employees to attend the meeting, spoke to the council about the social benefits of sharing one’s home. Many wore green stickers that said, “Protect home sharing.”

David Lesser, the only council member to vote against the ban at the June 16 hearing, said he would have preferred a more nuanced approach. (Lesser had initially supported the ban but changed his mind after hearing from homeowners who would be negatively impacted).

“We should have explored the different gradations of how you can restrict the problematic short-term rentals rather than taking a broad approach of an outright ban,” he said.

Now, Lesser is concerned the ban will drive the industry further underground, as short-term rental hosts weigh the risks of being caught, or alienating neighbors, against the chance of making relatively easy money — or, as some Airbnb users claim is equally as important — making friends with visitors from around the world.

For Seagars, who said he was priced out of raising a family in Manhattan Beach many years ago due to taking work as a government biologist, the ban is just the latest part of a trend of increasing exclusivity that he’s witnessed over decades.

“It’s really a shame that we’re so exclusive,” he said. “There’s got to be room in this community for everybody, and that includes visitors … Staying in a vacation rental is such a different experience than staying at a fancy shmancy hotel. You can be yourself in a vacation rental. You can talk to the neighbors and sleep in a comfortable bed. That’s a valuable experience. We ought to be able to provide that to a few people. That’s the town I used to know.”

One company that was apparently unaffected by the ban is Home Exchange of Hermosa Beach, which allows people to swap houses free of cost by paying a membership fee to the company.

“Home exchange is not included in any ban that is talking about renting or leasing,” Home Exchange Chief Executive Ed Kushins said.

Old-fashioned daily or weekly beach vacation rentals have been common in the Beach Cities for many decades. Hermosa Beach Mayor Peter Tucker said he first saw a major uptick during the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, when local residents skipped town to avoid feared congestion on the freeways.

But they’ve never proliferated as quickly as they have recently, thanks to the ease of hosting or renting through Airbnb or VRBO. By tapping into the so-called “sharing economy,” which includes sharing photos on Facebook or rides on Uber, the short-term rental sites have also become part of the cultural zeitgeist.

The rentals have become so prevalent that virtually every coastal city is now forced to address the issue. Last month, Santa Monica passed a ban of its own on short-term rentals, although it carved out an exception for rentals of spare bedrooms if homeowners agree to pay the city’s 14 percent hotel bed tax. With Manhattan Beach following suit, other cities are paying attention.

“It will be interesting to see how our council reacts to what Manhattan did,” Tucker said.

Other local governments are testing out regulations. Earlier this year, Malibu agreed to allow vacation rentals as long as visitors pay Malibu’s 12 percent hotel bed tax. The tax is collected by Airbnb and delivered to the city quarterly, starting this summer. Even so, Malibu Mayor John Sibert said the arrangement might not be permanent.

“After this summer we will revisit it,” Sibert said. “We might end up doing the same as Manhattan.”

Hermosa is also expected to revisit the issue at some point and either increase enforcement or opt for regulation, although the current city council has not thus far made it a priority. A ballot measure going before voters in November to raise the city’s hotel bed tax from 10 percent to 12 percent stipulated that the tax increase would apply to short-term vacation rentals, as well as hotels and motels, should the city decided to begin regulating the industry.

Even after last week’s council action in Manhattan Beach, the issue is far from settled. Some in the short-term rental business are filing an appeal with the California Coastal Commission, which seeks to ensure coastal access for all people, and hoping to have the ban overturned.

Robert Reyes, owner of Sunny California Vacation Rentals in Hermosa Beach, which manages nine of the previously licensed short-term rentals in Manhattan Beach, said another option would be to pool resources from homeowners for a legal defense fund.

“I’d like to see a coalition, and for these homeowners to get some legal fees to fight this,” he said.

Others are working to curtail future crackdowns. Robert St. Genis, director of operations at trade group Los Angeles Short Term Rental alliance, said the organization is trying to improve the image of the industry, for example, by encouraging members to vet guests before booking and communicating to cities how much they have to gain from additional hotel bed taxes.

He said he expects the recent bans to come back under review eventually.

“They’re all going to have go back and revisit it,” he said. “It’s an industry that’s here and it’s just growing.”

Staff reporter Caroline Anderson contributed to this report.