Music and Meditation

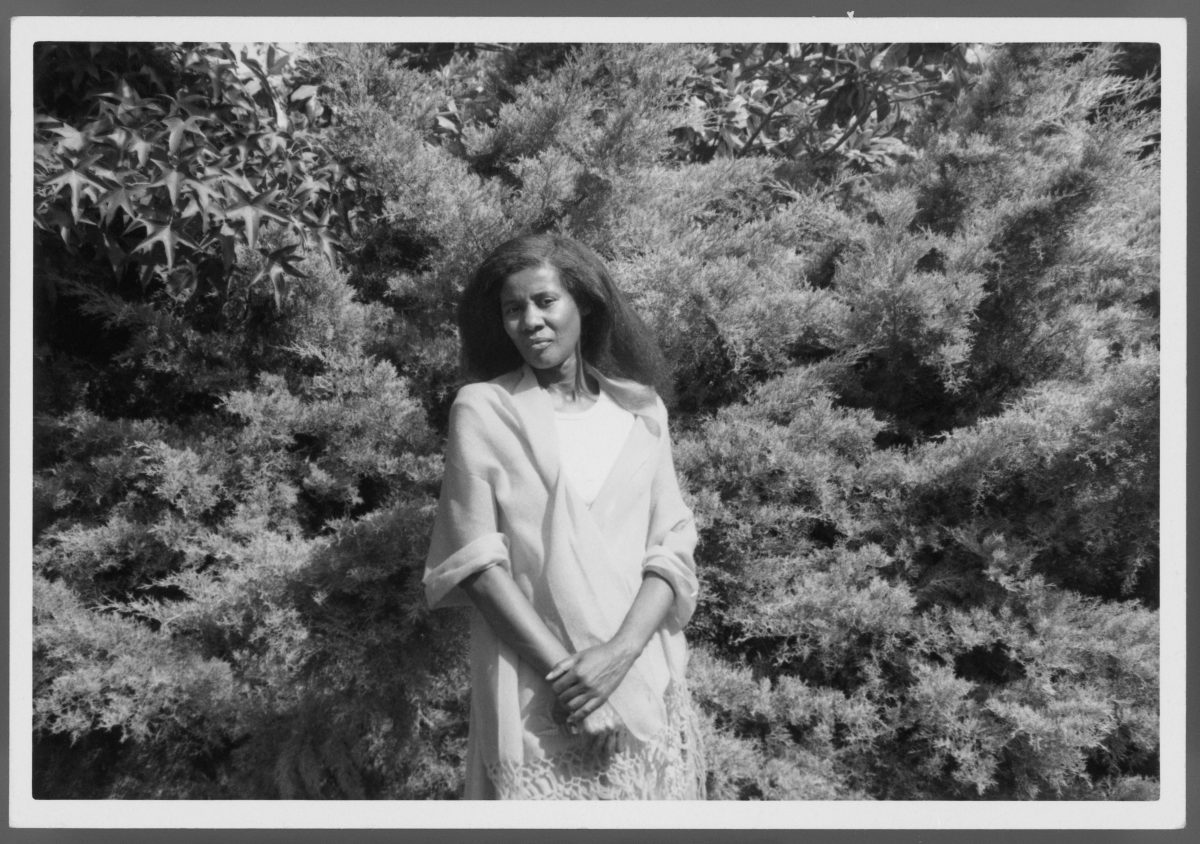

“Alice Coltrane, Monument Eternal” at the Hammer

by Bondo Wyszpolski

Somewhat in the vein of the recent Joan Didion exhibition, the Hammer’s current offering, “Alice Coltrane, Monument,” is a sprawling look at the life and legacy of the jazz pianist and spiritual leader, better known as the wife of saxophonist John Coltrane, despite the many recordings she released on her own.

Alice McLeod was born in 1937 and grew up in the postwar Detroit area. She learned piano at an early age and went to Paris with her first husband where she met and became friends with the pianist Bud Powell. Later, separated from her husband, Alice lived in New York with her daughter Michelle and played piano with the Terry Gibbs Band. It was at the Birdland Jazz Club in 1963 that she met John Coltrane, a decade older and already well known.

Alice was left with four young children. I’m not exactly sure how she coped with such a devastating loss, but she did compose and release several albums between 1968 and 1972, first on Impulse! Records and then Warner Bros. Increasingly, they reveal Alice Coltrane’s spiritual proclivities. This was an interest of hers that began when she and John tapped into Eastern and African religions.

In 1972 the family moved to California, and from San Francisco they relocated to Woodland Hills. Now known as Mother Turiya — her full spiritual name being Swamini Turiyasangitananda (“the transcendental lords’ highest song of bliss”) — Coltrane started an ashram that operated out of her home. In 1983 she purchased 48 acres of land in Agoura Hills, the ashram being named Shanti Anantam (before being renamed in 1994 as Sai Anantam Ashram). This was a religious enclave, retreat or community with a spiritual agenda.

In the three decades that followed, Alice made numerous pilgrimages to India, along with other members of her ashram. The book accompanying the exhibition doesn’t say how she was able to finance or support all of these endeavors, but one can assume it was largely through the residuals for her and John’s many recordings.

Alice Coltrane died in January, 2007, of congestive heart failure. She was 69.

The ashram property was sold in 2017, and then it burned a year later in the Woolsey fire.

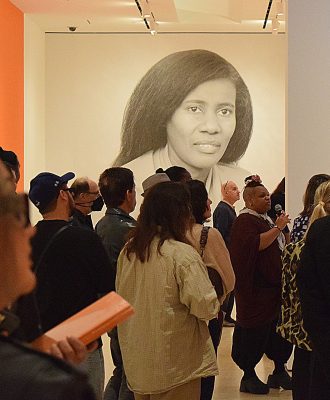

The exhibition, curated by Erin Christovale, takes its title from Alice Coltrane’s first book, “Monument Eternal” (1977), which documented her life from 1968 to 1970. In 2010, Franya J. Berkman published “Monument Eternal: The Music of Alice Coltrane,” an excerpt of which is included in Christovale’s catalog.

It should be mentioned that Alice Coltrane was accompanied on several of her early recordings by such notable sidemen (and band leaders) as Jack DeJohnette, Charlie Haden, Ron Carter, Pharoah Sanders, Carlos Santana, and Hubert Laws. What the book lacks — and I didn’t see any of this in the exhibition itself — are recollections from any of the above from when they worked on her records.

For that matter, a CD, inserted into the book, with thoughtful liner notes, would have been the cherry on the topping.

In Christovale’s words, “When I think of Alice Coltrane — her cultural influence, her genre-defying music, her deeply disciplined devotional practice, and the many lives she has sparked around the world — I’ve come to the conclusion that she IS Monument Eternal, an everlasting presence holding court in a shared collective unconscious.”

The catalog contains a long interview with two of the Coltrane children, Michelle and Ravi. They were merely kids in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, before the move out West, so their memories of living on Long Island are vague, albeit happy, at least in retrospect, and apparently without remembering much about their father.

If there’s any value to the book, and to the exhibition, it pretty much ends here, despite the inclusion of works — some made for the show, some not — by 19 young artists who, we are led to believe, feel some connection to John or Alice Coltrane.

Many of them seem conflicted by the trendy (or is it timeless?) issues of gender and identity, wringing their hands in public as they reference the African diaspora, for example, to which one might facetiously reply: Do you really think of returning to your ancestral homeland where your hut will be razed and your family cut down by machetes? And then the gender thing, so much in the open these days; the pronouns, whether one might feel more as ease in trousers rather than in a skirt or vice-versa. I’m exaggerating, of course, but I looked at their work and read the catalog cover to cover and mostly was not impressed because I often failed to see the real connection between their contributions and the life stories of the Coltranes.

Here’s a sampling of what I observed or read, and some reactions, stated or implied:

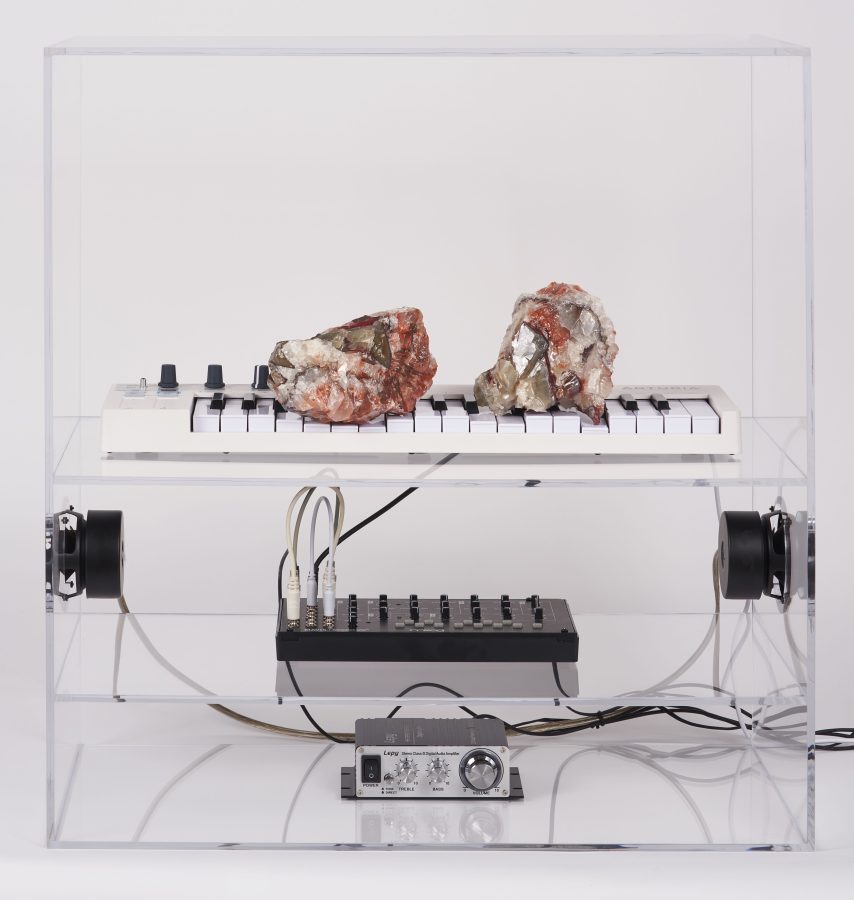

Nikita Gale has placed “two head-size chunks of red calcite… on the keys of a digital piano within a Plexiglas box. The resulting notes are amplified via speakers.”

Referring to Geovanna Gonzalez’s “PLAY LAY AYE: ACT I,” Nyah Ginwright says that “the work was activated in 2019 at the Bass Museum in Miami among queer artists and activists of color sharing with one another what openness and outness means as a community.”

Jennie C. Jones has several acoustic panels, with some yellow lines in acrylic to presumably evoke the minimalist effects of Barnett Newman. They resemble soundproofing material presented as art.

Nicole Miller, Ginwright explains, “creates work that transmutes light and sound to reconsider personal histories and prompt an understanding of one’s own body.”

Gozié Ojini breaks apart salvaged pianos and displays some of the debris as sculpture. Dayal: “Like a fence wrecked by a hurricane, the work indexes catastrophe, the sonic event of its making.”

The above plays well in L.A., but it’s partly why we have Trump and not Harris in the White House.

February 9–May 4, 2025. Photo: Sarah Golonka.

Ultimately, despite objects of interest here and there, and well arranged installations, I can’t guess how this project got greenlighted because all the essential stuff we may want to know about Alice Coltrane — her life and struggles in the jazz world — is not readily apparent. The spiritual aspects? So what? And why Coltrane? Why not Nina Simone or Sarah Vaughan or Aretha Franklin; why not Diana Krall or Carla Bley?

Alice Coltrane, Monument Eternal is on view through May 4 at the Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd, Los Angeles. Hours, Tuesday to Thursday, 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.; Friday, 11 a.m. to 8 p.m.; Saturday and Sunday, 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Free; parking about $22. Call (310) 443-7000 or visit hammer.ucla.edu. ER