by Rachel Reeves

In 1939, when Peter Serrato moved to Redondo Beach from Boyle Heights, plots of land were $50, the drugstore was closed on Sundays, and Mexican-Americans like him had to sit in the corner of the classroom if teachers overheard Spanish words.

A truck selling vegetables came through neighborhoods, announcing itself with the clanging of metal, once a week. Maria, the street where Peter’s dad built a clapboard house, was an unpaved road without a name.

Redondo Beach was populated by fields of flowers and corn, jackrabbits, goats, and about 13,000 people. The avenues were covered not in houses but in rows of tulips, rainbow asters, and mums. The strip mall behind Beach Cities Health District was a pig farm.

“Just dirt,” said Gloria Serrato, Peter’s wife of 74 years, who also grew up in Redondo Beach. “All dirt.”

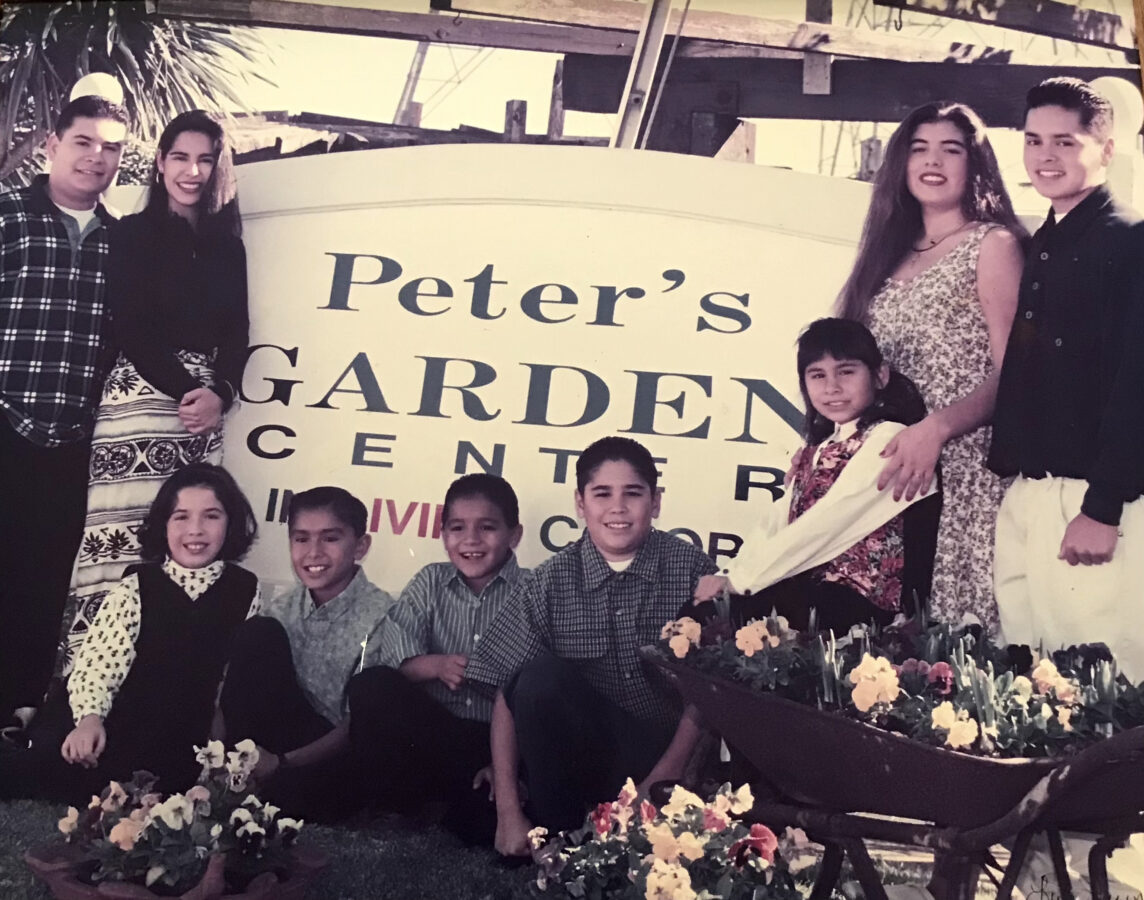

In Peter’s lifetime, Redondo Beach transformed from a hilly stretch of flower fields to an enclave of affluence described by Money Magazine as the fifth best place to be rich and single in America. Peter died last month. He leaves behind Gloria, five daughters, nine grandchildren, 18 great-grandchildren, and his namesake, Peter’s Garden Center, the nursery on the corner of 190th and PCH where decades’ worth of schoolkids took field trips and actor Gene Autry used to buy his Christmas tree.

Relocating to Redondo

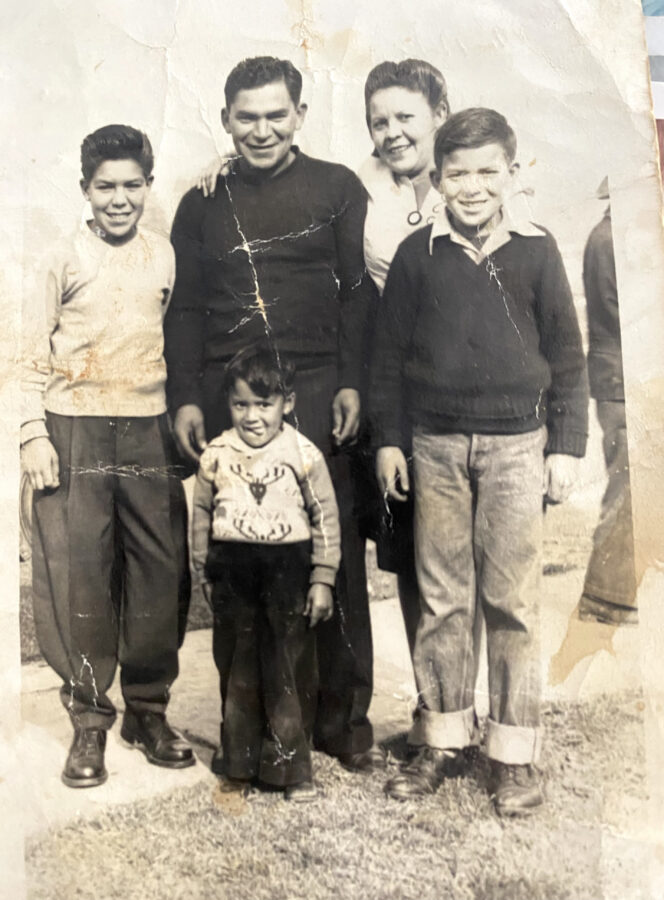

Peter’s father, Pedro, worked for a landscaping company in L.A. that once sent him to Redondo Beach for a job. He went home one night and told his wife, Consuelo, they were moving to the seaside. Within three months, the Serratos and their children had moved into a home behind the old car wash on Torrance Blvd. Peter was seven years old.

Suddenly, he was cut off from his cousins in East L.A. and his work shining shoes at Union Station to earn money for French dips at Philippe’s. His family had moved from what the L.A. Times described, in a newspaper clipping Peter saved all his life, as “the Chicano heartland of Los Angeles” to a largely Anglo neighborhood near the beach.

“It took Dad a while to get used to Redondo Beach,” his daughter, Connie, said. “It was a different world.”

For years, Peter took the bus, alone, to L.A. to visit his family.

His father did landscaping work in Palos Verdes and throughout Los Angeles, including at the historic sandwich stand Johnnie’s Pastrami in Culver City.

A year or so after the Serratos moved to Redondo Beach, Southern California Edison issued a bulletin announcing that whoever agreed to maintain the land beneath the power lines running along 190th, which was then choked by weeds, could lease the tract at a discount. Pedro cleaned up the land and cleared it to grow dahlias, rainbow asters, marigolds, corn, carrots, and squash.

“Peter’s dad used to grow the best corn ever on that hill,” said Chuey Hernandez, who was Peter’s close friend for over 80 years. Pedro sold his corn out of a little wooden stand on 190th. When he went home for the day, he left corn and a paint can on the counter with a sign that said “Leave money here.”

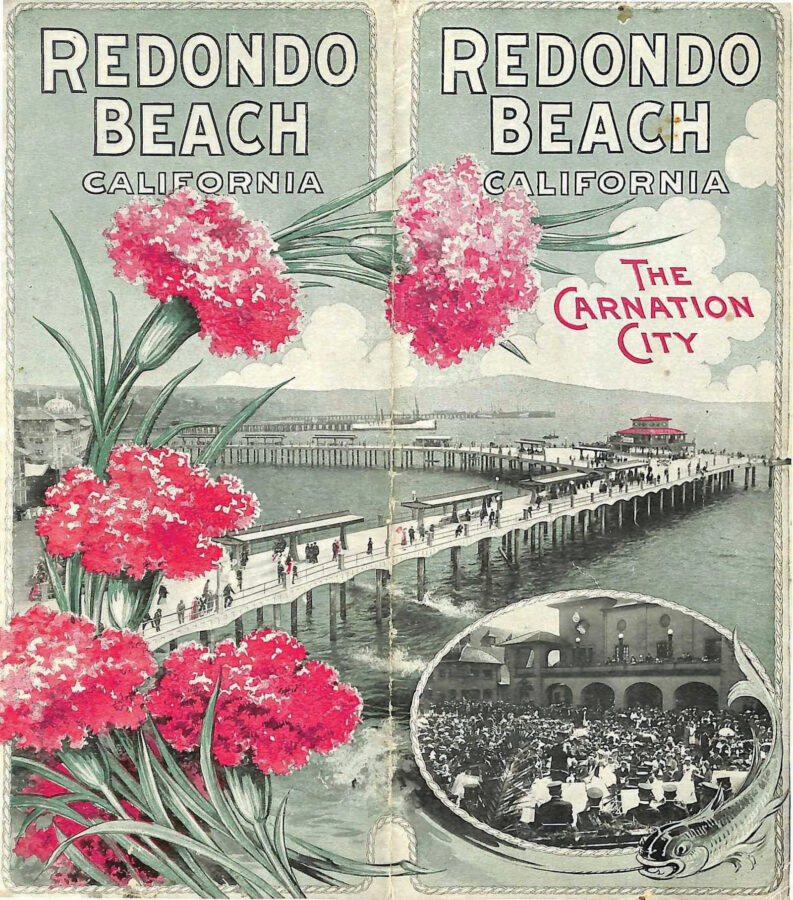

At the turn of the 20th century, Japanese-American families tended large commercial flower, fruit, and vegetable fields throughout the Beach Cities. The temperate climate gave them an advantage, allowing them to grow out-of-season flowers. In large part because of these families, as well as some Greek-American and Italian-American families, Redondo Beach became known as Carnation City.

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, many of the farming families were forced into internment camps. Their sudden detainment left fields and businesses untended. According to “Beach Mexican,” a book by Alex Areyan honored with a civic award from the City of Redondo Beach in 2007, that’s when many Mexican-American families in the Beach Cities moved into flowers.

“During these years,” Areyan wrote, “the Mexican-Americans’ strong work ethic stimulated the area’s economy and contributed to the expansion of the Los Angeles flower market.”

Pedro opened Redondo Home Nursery on the plot bordering PCH and 190th in 1941. The office was a wooden trailer painted red. The nursery did well enough that he bought a black and white television, the first in the neighborhood. Students from Beryl Elementary would take field trips to the Serrato home to watch it.

At Beryl, Peter befriended Chuey. Together they’d take the bus to Los Angeles to listen to big band orchestras practice at the Million Dollar Theater and share a 25-cent pastrami sandwich at Johnnie’s before heading home.

Once, when they were about 11, they took the bus to L.A. to buy shoes with the money they’d made delivering the L.A. Times and growing flowers for the nursery. Peter noticed a kid staring longingly at the shoes in the window display. He watched the kid offer three dollars to the cashier, who told him it wasn’t enough.

“The young boy just stayed at the display and kept looking at the shoes,” Chuey recalled. “I was walking out and Peter said, wait a minute, I’m gonna give him my shoes.”

The boy beamed.

“I can’t pay you,” he said.

“I’m not asking you to pay me,” Peter replied. “But when you get older, you see somebody that needs help, you give them money and don’t expect anything to come back. Remember what I did for you. I don’t want you to pay me. I want you to help somebody else.”

Peter attended Beryl and the now-defunct Central School, and then Redondo Union High School.

In “Beach Mexican,” Areyan uses the Serrato family as an example of how “assimilation was often easier for the few Mexican American families who owned their own businesses,” noting that Peter and his siblings “rapidly and successfully assimilated at Redondo Union High School through sports and other activities.”

The Princess

In 1948, when he was 16, Peter met Gloria Salinas at Fiesta Days, an annual festival sponsored by the City of Redondo Beach in the 1940s. The festival, which took place downtown, in the stretch of waterfront where Captain Kidd’s is now, recognized the city’s Mexican-American heritage and community. People dressed up and made ¡Viva México! signs for the celebration. It featured a float parade, dancers, horse-drawn wagons, and booths selling Mexican specialties, including Pedro’s corn.

Gloria was 16 and beautiful; she had been voted the princess of Central School. Peter was smitten. Her first impression was that he was “just a regular guy.”

“What made you want to date Grandpa?” her granddaughter Qiana asked her recently.

“Well,” Gloria replied, “because he asked me.”

Peter walked her to every class. They went swimming in the ocean at Second Street in Hermosa and saw 50-cent movies at Fox Theater, now the grounds of a music festival that attracts 60,000 people annually.

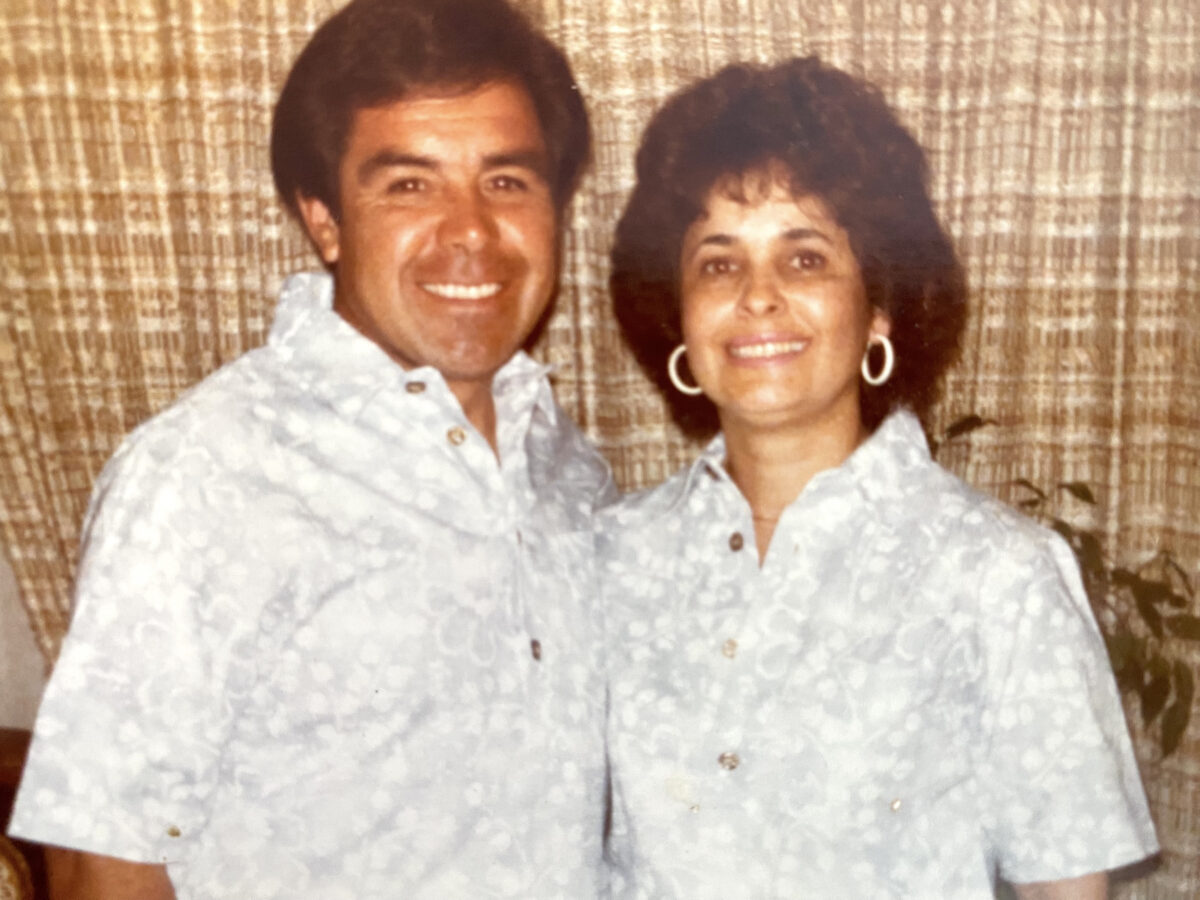

“I fell in love with him because he was kind and sweet and would look at me with his big brown eyes,” Gloria said.

They married in 1950. Peter left school to get married; he later attended night school to get his GED, then studied botany at El Camino College, where he educated his teacher about growing plants.

He and Gloria had five daughters, who mowed the lawns and tended the gardens. He took his daughters for drives to Palos Verdes, to penny candy stores on Catalina Island for watermelon candies, and to the Redondo Pier for a single malt, which all five of them had to split. Every New Year’s Eve, he took the whole family to Reuben’s for steak and seafood.

As a young father, he worked as a maintenance foreman for the City of Rolling Hills Estates. He signed off on the large green and white street signs for which the city is known. (Later, when he took over his father’s nursery, he’d identify it with a sign in the same style.) In 1955, he bought a house on Speyer Lane for $9,000.

Peter’s Garden

Pedro died in 1979. A year later, Peter renamed the nursery Peter’s Garden Center. He earned a state certification in landscaping and employed all five of his daughters.

Together they grew and sold pansies, petunias, marigolds, dianthus, dahlias, and lobelias to 20 other nurseries, from Palos Verdes to Pacific Palisades. Every week they delivered cut flowers to the Los Angeles Flower Market downtown.

Peter’s Garden Center’s tagline was “if we ain’t got it, you probably don’t need it.” The Beach Reporter reported the nursery stocked “virtually everything” in an article titled “The South Bay’s Best Kept Secret.”

People came from all over Los Angeles to find hibiscus and bougainvillea, even in winter. The nursery sold pumpkins for Halloween, fresh-cut roses for Mother’s Day, and, at the end of each year, flocked Christmas trees in purple, yellow, green, blue, red, and white.

“People came from far away to buy Christmas trees,” Connie said.

“They were gorgeous,” added Peter’s daughter Gloria. “No other nurseries were doing that at the time.”

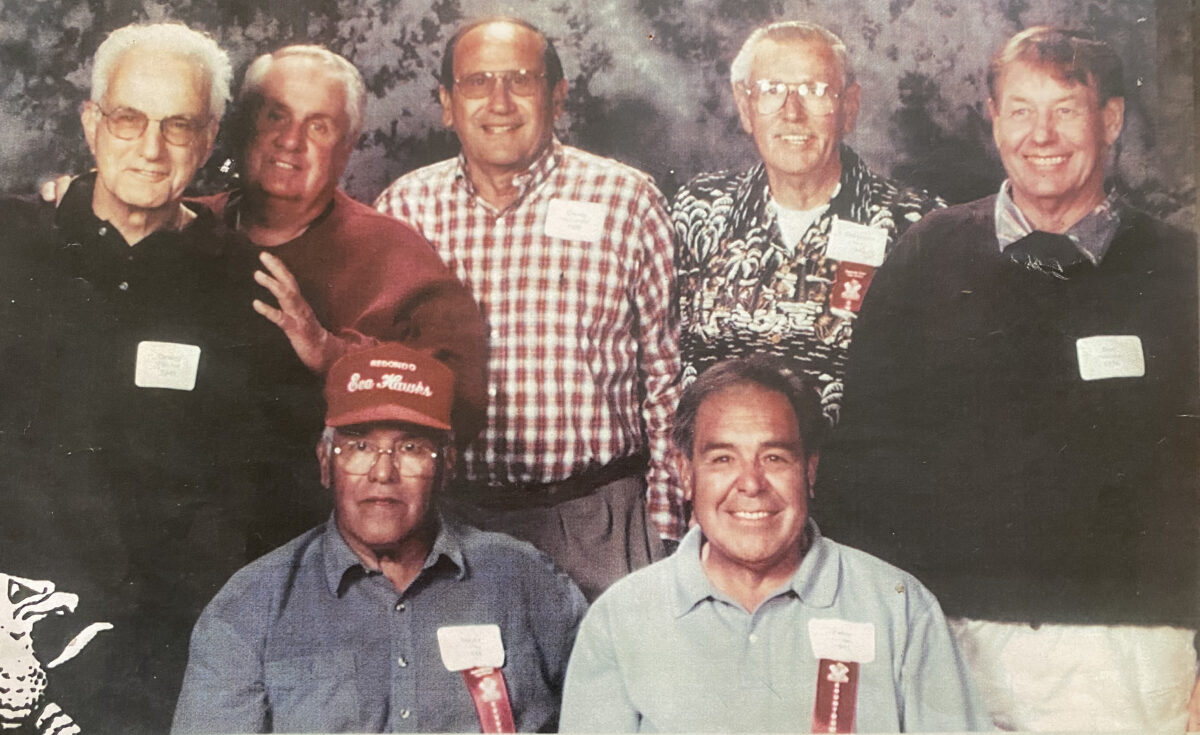

Even after Peter handed the nursery’s reins over to his daughters, he continued to show up there daily. Until he stopped driving, he met his friends from high school in the office on the corner of 190th and PCH every morning at 7 o’clock. They’d eat donuts, drink coffee, and talk about their glory days playing football at Redondo Union High. They called themselves Senile Seahawks.

A language all his own

According to his family, Peter loved making jokes, watching football and track, eating menudo, and wearing his pajamas.

He spoke a language all his own: coffee was “javvy,” newspapers were “stoolies,” and gossip was “the skinny.” Drunks were “mopheads,” people he liked were “slick,” and a “rasconi” was a roughneck. He answered the phone “Duffy’s Tavern, Duffy speaking;” no one in his family knows why. He wanted the headline of his obituary to read “Peter Serrato kicked the bucket.”

He was intentional about creating spaces for people to gather in. He had barbecues for his workers. He invited his family and friends over for breakfast on Sunday mornings. He maintained the same friendships all his life, nurturing them even when he was too sick to leave his reclining chair.

“I used to call him when he was ill and I’d say okay, listen, pay attention to what I’m telling you. The game is on Channel 11,” Chuey said. “He’d use his phone instead of the remote and punch the numbers and it would go in my ear and I’d holler, Peter! Oh, dammit!”

Peter’s journal reveals the kind of fastidiousness and focus required to be successful in business. He documented every pill he took (“One Zantac at 9:05 a.m.”), everything he ate (“small bowl of chicken soup and two corn tortillas at 12:00 noon”), what he fed his flowers, new vocabulary words, and songs he liked, mostly romantic oldies numbers. He jotted down quotes that aligned with his core values: “We have enough religion to make us hate, but not enough to make us love one another” in 2008; “No man has a right in America to treat any other man tolerantly, for tolerance is the assumption of superiority” in 2012. Respect was one of his guiding principles.

“He was very, very honest and very, very good,” Chuey said. “If he saw somebody who needed help, he’d give them help and he wouldn’t expect anything back.”

He gave money to Beverly, the alcoholic who begged outside the 99 Cent Store, every time he passed her.

“People would say, why are you giving her money? She’s going to go on and probably buy liquor,” Chuey said. “He’d say, ‘I give her money because she needs it. How she uses it is up to her.’ That’s how he was.”

Once, a man who was transporting produce from San Diego to Imperial Valley got lost in the fog and ended up on 190th. Peter spoke to him on the side of the road in Spanish, invited him home for dinner, then led him back to the freeway after the meal. Another time, Chuey’s niece wanted to have a birthday party in her uncle’s two-bedroom house. Chuey told Peter he couldn’t fit everyone. Peter brought over some two-by-fours and rocks and, within a few hours, he’d built a patio that could accommodate a whole party and a firepit.

Peter watched Redondo change dramatically around him. The change, as always, was double-edged. He moved to the seaside when Dominguez Park was a landfill, and then, years later, watched his grandchildren play baseball on the diamonds there. The city grew from “a great little town to grow up in,” in Chuey’s words, to what Gloria described as a place that’s “crowded and packed with people.”

But as it all swirled around him, Peter remained rooted. His love for and loyalty to his adopted city and the people he shared it with never changed. He held fast to his friends, his traditions, his employees, and his business. He held his wife’s hand until his final day on Earth.

“I miss Peter being by my side,” Gloria said. “He would not look at anybody else except me. He never had eyes for anybody else.”

To sign the mortuary’s guest book, visit https://lafuneral.com/obits/peter-frank-serrato/. ER