Second of two parts

The little girl always loved school. She came from an immigrant family in which education was especially valued, but it was more than that. She loved everything about going to school, from the smell of the paper and books and freshly sharpened pencils to the way it felt to learn something new each and every day. Most of all, she loved her fellow students.

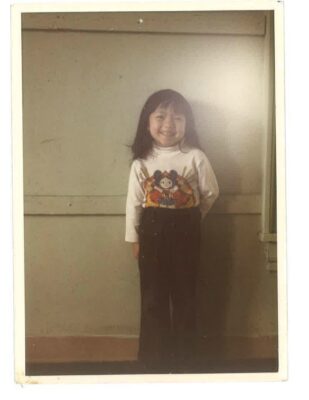

And then, in third grade, at Lyndale Elementary School in San Jose, California in 1985, Chau Ly found a teacher who truly loved her. She was an easy student to love. Beneath her mop of long dark hair, she was bright-eyed and industrious and possessed an almost imperturbably happy disposition. But that teacher, Debbie Schroeder, also sensed something amiss beneath the surface.

They had a special connection. Schroeder made Chau her unofficial teaching assistant and full time tag-along. She’d help pass out papers, erase the chalkboard, and make copies of worksheets for the class.

“She was so smart and so kind and a very good student,” Schroeder said. “Everyone loved her, of course….She always helped kids who were struggling. She never complained, and was just so willing to always be there for everybody. Even for me. Because at that time I had 30 kids, with very diverse needs. That’s a lot.”

Chau took a special interest in a hearing impaired boy, a special needs student who’d been “mainstreamed” into the general education class. She diligently applied herself to learning American Sign Language. She wanted to be able to talk to the boy so she could help him.

“I wanted him to be part of the group,” Ly remembered. “I knew he was different, and the quicker I knew how to communicate with him through sign language, the more I felt connected with him, and the more he felt connected to the classroom.”

At home, Chau would teach to an imaginary classroom full of students. The family lived in poor part of San Jose. Her father, John Ly, was raising three children in a country he’d only recently arrived to; he and his wife, who had wed in an arranged marriage in their native Vietnam, had suffered the dissolution of their marriage a few years after arriving in the U.S. in 1980. The family scraped to get by, so Ms. Schroeder would send leftover school supplies with Chau for her imaginary classroom.

“Our family had little — and these extra sheets of papers made me feel happy and full,” Ly said.

She distinctly remembers, as a seven year old, feeling one certainty: when she grew up, Chau was going to be a teacher. Ms. Schroeder saw it in her, as well. But she also saw a little girl very much missing her mother.

“What I remember about her is, at the time, she needed a mom,” Schroeder said. “I was a like a big sister-mom.”

She inquired about adopting Chau. Her mother now lived on the other side of the country, in New Jersey. Her father, new to American culture, was puzzled by the request, and at any rate her mother was still very much in her life, albeit from far away. But it mattered to Chau that Mrs. Schroeder cared for her so much. It mattered that an adult outside her own family saw her as someone special.

“She made me feel very happy being in school,” Ly recalled. “I think I would have been happy anyway….but she sure helped me learn about how special I was as a child.”

Things changed for a while when she was a teenager. Both her siblings, a brother and a sister, were academic stars. Both were valedictorians at their high school. Chau was also a exemplary student and likewise a valedictorian. But she felt less intelligent than her siblings.

“I was the black sheep, to be be honest,” she said. “I could never be smarter than my brother or sister. We were all valedictorians, but I just couldn’t compete with them.”

She attended the University of California at Santa Barbara. In keeping her parent’s wishes, and the culture she grew up in, she majored in math and computer science. “Everything in my childhood and my cultural values and in the personal message from my immigrant father was, ‘I came here to give you a future, and education is the number one thing.’ You have to excel, and you have to succeed.”

During her junior year, she took a Greek mythology class as an elective. One day, while deeply immersed in a story, the realization dawned on her that she needed to switch majors to English.

“It wasn’t the actual story itself,” Ly remembered. “Growing up, I just loved reading and writing. I took that class and it reminded me: I want to go into something I love.”

The call to her mother, Yanne, was one of the more difficult conversations of her young life. She had always deferred to her parents. Her mother, who kept very close watch on her daughter’s education, was disappointed.

“What do you think you are going to do with an English degree?” she asked her daughter. “Be a teacher?”

After graduating, she moved to L.A. with exactly that intention. She took a summer job as a special ed assistant aide with The Help Group, a nonprofit that runs day schools for students with special needs. After two months she was offered a fulltime teaching position. She declined.

“In my mind, I was like, ‘Are you kidding me? I can’t handle the kids,’” Ly said. “I couldn’t see myself working in this population. I couldn’t see myself interacting with kids who were very impacted.”

Throughout her own academic career, Ly had been in programs for gifted students, such as GATE. In high school she was an Advanced Placement student. She’d assumed her teaching career would be among such “high ceiling” students. She’d never considered working in special education.

Instead, she went to work in a series of private schools. She taught general education, with a focus on gifted students, and began graduate studies at Loyola Marymount University. After obtaining multi-subject certification and a master’s degree in arts of teaching English, she enrolled in a LMU’s special education program. There, under the tutelage of Father Tom Batsis, she began looking at special education through a different lens — through the very motivators behind learning and behavior, the very groundworks of education itself.

“He taught if you change the motivation stimulus, your whole personality can change, and your work productivity can change,” Ly said. “So he really taught me the psychology behind special education.”

Six years into her career, she took a special education job at a private school, Westview School. What she had learned theoretically at LMU had drawn her to this student population; what she discovered in the classroom made her realize she’d found her calling.

She has now been teaching special education for 12 years, the last 10 with the Manhattan Beach Unified School District. Last June, she was named Pacific Elementary’s Teacher of the Year. Even her mother’s original misgivings have been replaced with pride, knowing her daughter lives for others. “My mom cries tears of joy knowing what I’ve become,” Ly said.

The special quality Ly found wasn’t her students’ “impactedness” — the professional education jargon referring to which of the 13 categories, from learning disabilities to physical impairments, that under law make a conventional learning setting insufficient and qualify a child for special education. Rather, there are other qualities that stand out to Ms. Ly, as she is now called. The vulnerability these kids feel, borne of the challenges they face, confer upon them a special sweetness. They are so innocent and so scared. It is early in their lives, but they’ve often already felt the sting of perceived failure, of judgement, of not being like other kids. They want to do better but don’t know how.

Ms. Ly took 10 years of fulltime graduate coursework at LMU while also teaching full time. She also obtained a degree in administration. But she has not left her classroom. She has fallen irreversibly in love with special education students.

“These are the kids,” she said, “I want to interact with the rest of my life.”

Life rafts

The history of children who don’t learn the same way as most children is littered with words indicative less of their actual condition and more with the harsh societal perception of those outside the norm.

Jonathan Mooney, a former special education student from Manhattan Beach, is the author of two groundbreaking books, “The Short Bus: A Journey Beyond Normal” and “Learning Outside the Lines.” He notes that descriptions of such cognitive states have evolved from the 19th century’s “feeble-mindedness” to the 20th century’s “mental retardation” to today’s “developmental disability.”

Mooney suggests there is another step yet to take.

At a TEDx talk a few years ago, Mooney, who entered 6th grade suicidal and unable to read, recalled his “fraught” relationship with school desks from first grade all the way along his eventual path to Brown University. He was one of those kids who just couldn’t sit still, and he suffered for it.

“That young person is shamed,” Mooney said. “Because a core part of education is the good kid is the compliant kid, and the good kid sits still.”

He remembers an elementary teacher he calls “Mrs. C” stopping class and confronting him when she saw his foot bouncing beneath his desk. “Jonathan,” she shouted at him. “What is your problem?”

“The learning revolution starts with rejecting that idea that if you don’t sit still you’ve got a problem,” Mooney said.

In an interview this week, Mooney recalled another teacher at Pennekamp Elementary, third grade teacher Mr. Rosenbaum. Mooney couldn’t spell accurately and had developed anxiety about even trying to write. One day, Mr. Rosenbaum turned to Mooney and said something that changed his life.

“Jonathan,” he said. “Screw spelling.”

The intention behind those words would be with Mooney the rest of his life.

“It was such a small thing to say, but a totally radical thing to say,” Mooney said. “Mr. R was not only an immediate life raft, he planted some seeds and laid a foundation that I really carried with me. He was just a lifesaver for me. He was all about, ‘What can I do differently as an educator, and what can the environment do, and how can we change to meet your needs?’ He taught me that I didn’t just have deficits, but a lot of strengths.”

“Everywhere I go, I celebrate him.”

The evolution of special education mirrors Mooney’s experience.

Advocacy groups focused on the needs of such students formed early in the 20th century; at that time, kids today we call “severely impacted” were often either institutionalized or left entirely unschooled. By 1961, President John F. Kennedy created the President’s Panel on Mental Retardation, which recommended the federal government provide aid to states to help such students. This was in part achieved in 1965, when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which expanded public education to include special needs children. A decade later, both the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA) and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) were enacted. The EHA established a right to public education for all children regardless of disability, while the IDEA required schools provide individualized or special education for children with qualifying disabilities. Finally, in 1992, the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) explicitly gave legal protections against discrimination and included students with learning disabilities.

“This was civil rights legislation,” Mooney said. “Consider that a whole class of humanity until 1975 — not 1875 — could be denied education. This couldn’t happen anymore; that was a huge step. And then along came ADA in 1992 , which guaranteed the rights of people with disabilities to reasonable accommodations like curb cuts and time extensions on exams — essentially a bold statement that said said the system needed to change, not the person.”

Educationally, one of the key provisions was Individualized Education Program (IEP) required for each student qualifying as a special needs student under IDEA. This is still the fundamental document used in special education. An IEP is developed for each student. Once a student is identified as needing an IEP — as needing more personalized instruction than a conventional classroom can provide — a team is formed. It is comprised of the special ed teacher, usually a general ed teacher, sometimes the student, always his or her parents, an administrator, and — depending on the student’s individual needs, possibly an occupational, speech, or physical therapist, or school psychologist. Sometimes a lawyer representing the family may even be involved. The IEP evaluates the student’s current level of academic performance, including strengths and weaknesses, then sets goals, and defines what support and accommodations will be provided for the student. It’s a fluid document. Ms. Ly, for example, is on the phone most nights with parents, often discussing changes to the IEP. Most mornings, before the students arrive at 8:15 a.m., she’s already had one or two IEP meetings. Her special gift is her connection with individual students, but her lines of communication are extensive, and almost as essential. She has a caseload of 28 students, the legal maximum. She’s in contact with parents and other members of each student’s IEP team almost constantly. She wears an Apple watch so that no matter what she is in the middle of, she’s immediately aware of who is trying to contact her and able to respond as quickly as possible, especially with parents. It’s not unusual for her work from from dawn till late into the evening. On one recent night, she left dinner after already putting in a 12 hour day to talk with a parent about their child’s IEP. Last school year, another parent wanted to see records of everything her boy had done in Ms. Ly’s classroom for the last year. Ms. Ly and her teaching assistant were able to provide the mother records of every single activity the boy had done all last school year and so far this year. Ms. Ly was happy to go over the records in detail with the woman.

“This job is successful only in the collaborative mode,” she said.

The IEP is also a legally binding document, the consequences of which are something MBUSD knows a bit too well. In 2005, the district was forced to pay a local family, the Porters, what was at the time the largest settlement of its kind, $6.7 million, for failing to properly execute an IEP and for retaliating against the family when objections were raised.

But like the larger special education history, the local history is one of increasing awareness, responsiveness, and innovation.

“Let’s acknowledge that this is evolving, as opposed to just, ‘Things were bad in the past and we’ve got to do something about it,’” said Mooney, who attended MBUSD in the early 1990s. “It’s about taking what’s good, most importantly in terms of inclusion, and getting better.”

MBUSD has 1,055 special education students out of a total student population of 6,659, which at nearly 16 percent of the student body is in keeping with the national average of 13 percent.

Mooney, who spoke to MBUSD teachers at the beginning of this school year, said he was impressed that the district had altered its special education evaluation model.

“It’s a system based on the idea — here’s five problems, but here’s also five strengths,” Mooney said. “Let’s also use school to build strengths, and not just remediate weaknesses. And that is happening all around the country. I know MBUSD is going to continue to grow, as they think about their role as a system not just about fixing kids…but about transforming the system around kids, and redefining kids like me as kids who have something to contribute.”

He also noted that the practices of special ed often are adopted for general education.

“One of the things that is so cool — special ed teachers were talking about personalized learning, using different words, long before it became a catchphrase, long before Mark Zuckerberg and everybody else who talks about the future of education. Special education teachers have been at the vanguard of education, thinking about what it means to educate a different continuum of human beings.”

Persistency

It’s midmorning and the four fourth graders in Room 27 are wrapping up their discussion of “The Tale of Despereaux.”

A little boy who mistakenly thought there was a murder in the book has calmly worked his way to the deduction that he misread an illustration. The sword didn’t hit anybody. His diagnosis as a special ed student includes ADHD, yet he’s sat calmly through a 20 minute group activity. He tapped his foot throughout the discussion, but quietly, unobtrusively, and stayed on point throughout. He gently acknowledges the girl across from him was right, and he was wrong. Everybody survived.

“Do they live happily ever after?” asks a pony-tailed little blonde girl.

“But happily ever after is…” the boy begins, then pauses, giving the matter some thought. Then he briefly runs through the fate of each character in the book, and determines that some of the characters may have been happy ever after.

“But some are prisoners,” chips in the little brown-haired girl.

A tussle-haired boy wearing a Messi soccer jersey looks weary. “You are yawning,” Ms. Ly tells him. “Just take a one minute break.”

Ms. Ly announces to her assistant that she is “transitioning” to another student, a cherubic but slightly wild-eyed third grade girl wearing a camouflage shirt sprinkled with stars. She is working by herself in the middle of the room. This little girl is autistic; she’s been coming to Room 27, also known as Pacific Elementary’s Learning Resource Center, for three years. Today she is a calm, jovial mood, and brightens further as Ms. Ly sits next to her. But it’s been a fairly dramatic journey for this little girl to get to this place.

On the wall on the other side of the room, above Ms. Ly’s desk, is a drawing the girl made for her teacher. It shows a heart with two hands inside its curves. Scrawled underneath the drawing is a message: “I will promise I’ll never put my hands on you again, Ms. Ly. I love you.”

The girl is very physically expressive and, though less so all the time, given to emotional outbursts. Throughout the day, she periodically takes little zig-zagging runs through the classroom. These flights could come off as threatening — she’d veer at somebody, then tail off at the last minute. Ms. Ly met her at her own level, in her own physical language. One day when the girl started doing her zig zag run, Ms. Ly just kneeled down and opened her arms wide. The girl ran into her embrace and hugged Ms. Ly.

“The biggest mistake every adult makes is trying to control the child,” Ms. Ly said later. “When really, you are not trying to get control of the child — you are trying to get the child to calm down. If you insist on control it escalates, because now you are participating and arguing with the child. Then the child thinks, ‘You don’t even care about me. All you care about are the rules.’”

“If you feel you need to keep control of the situation, you have already lost it. Our students are very hungry for control, because isn’t that the wider fight of their lives? It’s why they are fighting — because they feel powerless.”

The girl diagnosed as autistic felt this powerlessness acutely. Ms. Ly noticed early on in working with the girl that the way her day started invariably determined the whole day. In her general ed classrooms, the girl would often simply refuse to do any work, and from that struggle the rest of her day would spiral out of control. And so Ms. Ly used her daily task list as a means of addressing this. The girl uses it to chart her own day.

“We have her come in to a safe place, starting the day so nicely and positively,” she said. “When she is reintroduced into the classroom, she has a new outset — this is my morning, this is my day at school. A lot of these kids, they have to have some control over what their day looks like. At the same time, they have to know what they are controlling, and be accountable for their own learning. So her morning routine is really important.”

Ms. Ly’s teaching assistant, Shelley Johnson, has taught special education for 16 years. When she joined Ms. Ly three years ago at Pacific, she felt like she’d seen it all.

“I thought I had nothing else to learn,” Johnson said. “What strikes me with Chau is I am learning how to do things differently from her. The way she interacts with kids on all levels amazes me, but I also get to learn every single day….It’s how to teach the kids, how to interact with the kids. I come from a very old school, Italian background, so my first go-to is to yell and ask questions later. Chau is 100 percent the opposite. She is just so kind and nurturing. Even if the kid has done something wrong, she is so gentle about approaching the student. I’ve learned how to change my initial reaction.”

Through the task list, Ms. Ly also found a way to help the girl with autism find an appropriate mode for her physical expressiveness. For completed tasks, she builds up reward time. Once she’s built up an agreed-upon amount, she’s allowed to throw a dance party for the whole classroom.

Today, Ms. Ly checks the girl’s task list, which is already completed, and helps the girl strategize the day ahead. The fourth graders discussing Despereaux have all completed their reading comprehension worksheets. The little boy with the tapping feet has built up reward time. He has high play drive, so his reward is simply to use a classroom computer to play a math game.

Two of the other fourth graders, the pony-tailed blonde girl and a sweet-faced girl who wears a her brown hair in headband with a little white bow on top, move to another table together. They are an inseparable duo. In fact, they joined Ms. Ly’s room at the end of their second grade year together. The little blonde girl cried almost every day back then. At first, she refused to even talk to Ms. Ly or her assistant. Her general education classroom experience thus far had been terrifying; she was diagnosed with a specific learning disorder but hadn’t found a way beyond her fears yet. Her friend was a bit less traumatized, but she could barely read.

As Johnson notes, the two are barely recognizable as students. They run into the classroom smiling almost every day. Just last week, the pony-tailed girl found out Ms. Ly’s birthday was the next day (“A very tall bird told her,” Johnson said) and arrived the next morning with a little homemade “Ms. Ly” nametag for her teacher’s desk. The girl wearing the headband has become an avid reader.

“Now she is so excited to read, and she understands what she reads so well,” Johnson said. “She’s so happy about it. ‘Oh I can read, I can read!’ She’s reading her own tests and she’s having fun reading.”

In fact, it’s reward time for the little girls, and the brown-haired girl is rereading the “Tale of Despereaux” on her own time. The blonde girl likes to do art projects for her rewards; she’s drawing a red-headed mermaid.

“You like red,” Ms. Ly notes. “You like sweet colors.”

She turns to the other girl. “Make sure you are not just trying to read,” she says gently. “But read to understand.”

They take the opportunity to look at the girls’ reading worksheets together. One of the ways of analyzing the book on the worksheet is “text to self,” which means relating themes from the story to their own lives. One of the characters is named Miggery Sow, a mistreated girl who lost her mother when she was young and was sold by her father to a man how gave her “clouts to the ear,” making her deaf and somewhat simple-minded. But despite everything, Mig kept believing in her dream — she wanted to be a princess.

“Mig had to overcome many things,” Ms. Ly says. “The character trait is resiliency.”

One of the girls remarks that Mig is pretty odd. Ms. Ly agrees.

Well, I’m am a little bit odd, too,” she says. “But that’s okay.”

The blonde girl can identify with Mig. She recalls how she was finally able to convince her parents to allow the family to have a dog.

“Even though it seemed impossible to get a dog, I was persistent,” she says.

“I’m the same way,” Ms. Ly says. “I try and I try. Sometimes I fail, but I keep trying. And persistency is a very good quality to have.”

Her choice of words is not accidental. Persistence means to continue firmly in a course of action in spite of difficulty; persistency is the “state of being persistent.” It’s not a one-time thing. Ms. Ly is imparting lessons not just for the academic task at hand, but for life. She is trying to give the students “compensatory skills” because she believes that whatever learning challenges these kids face, they’ve also been given special gifts. Special education, to her, is just that — an education specially tailored to help children proceed in life with tools needed for success.

“These students may have difficulties, but they are born so tender into this world,” she said. “People don’t realize they are very sensitive to everything in their environment. Even though it seems they can’t do something, or can’t always communicate what they are experiencing, they are very hurt by a lot of things adults say to them. It’s almost as if they’ve developed a sixth sense because of their disability — they are super-sensitive to the world around themselves.”

Ms. Ly recalled a recent conversation with an IEP team member concerning one of her students in which the person suggested it was time to “confront” the child. She disagreed, and her reasons why were indicative of her deep advocacy for each of the children who come to her for help.

“You think this is a choice of theirs? If you really feel it’s a choice of theirs, you are saying they want to fail,” she said. “What person would want to fail in life? For me, I see children who can’t help themselves and that is why they are diagnosed with disabilities. And what we do as educators is help to compensate for deficits. We can’t fit them into a box. What needs to happen to help [the student] learn? What is it I can equip you with to help you learn better? Because whatever we can come up with, together, it’s going to show you how you are going to succeed when you get older.”

Jonathan Mooney, the little boy who couldn’t read who grew up to become a writer, exemplifies the arc of such a child. Like Ms. Ly tries to do each day with her kids, Mr. R — whose name is Peter Rosenbaum — gave Mooney the tool of self-belief. Much later on, he ran with this belief. He built a life containing successes that would have seemed unfathomable for most of his childhood.

“His focus was everybody has a talent, everybody has a skill,” Mooney said of Mr. Rosenbaum. “It doesn’t matter if you can’t read, sit still, or walk well. You’ve got something right with you.”

The eloper

Over the past few weeks, Ms. Ly’s classroom has had a new visitor. She’s a tough little customer, blonde and bandy-legged, with a defiant, slightly bemused glare in her eyes. She’s not yet qualified for special ed, but Ms. Ly has come to know her well because they share something in common. They are both runners.

Ms. Ly has shaped her entire life around serving her students. “For it is through giving that we receive” says a passage in the prayer of another famous outcast who defied societal expectations, St. Francis of Assisi. Nearly every moment of every day of Ly’s life is spent giving.

Her one personal allowance is that she makes time to run seven miles most days. One recent Friday morning, this practice was put into use.

The girl was already a known “eloper” at the school — meaning, she’d repeatedly tried to run off campus. On this day, it was 8:10 a.m. and Ms. Ly was just leaving the second of her two morning meetings when she saw an alert on her Apple watch. The girl’s parent had dropped her off in the front of the school, but they’d apparently been quarrelling. The girl bolted.

Ms. Ly was just arriving to the scene when she saw the girl take off. Special ed teachers are trained in a non-confrontational protocol; Ly directed two assistants to form a wall while she attempted to approach the girl.

What followed was almost 100 minutes of negotiations on the run. The girl gave herself up a few times, but then would bolt again. At one point, she broke free and appeared to be headed for the street. She was fast, but Ms. Ly was just as fast. There was an earthquake drill scheduled so she’d brought her running shoes. She caught up to the girl.

“I’m going to tell you something,” she said to the girl. “If you decide to keep running, I’m going to run just as fast. You picked a person who can run all the time. So keep running, and I’ll keep running with you.”

It wasn’t said as a threat, but as a promise: I am here with you. The girl stopped. They talked. The girl said she hated the school and wanted to go back to another state, where she came from. Ms. Ly had just gotten to know the girl, but she knew she’d been in California three years. It wasn’t about missing another place. It was about missing her mother and the way things used to be.

“My mom wasn’t around for me when I grew up, either,” Ms. Ly told her.

Eventually, the girl agreed to come to Room 27. In the weeks since, she has decided that’s where she wants to be, with Ms. Ly, who she gave a nickname on the morning they ran together: “Okay, Ms. Safety. I’ll come with you.”

Back in Room 27, the pony-tailed girl had news for Ms. Ly. When Ms. Ly “transitioned” from one of the other students and sat next to the girl, she apologized.

“Ms. Ly is very busy,” she told the girl.

“Yeah,” the girl said. “I tell my students at home I am busy like you.”

It turned out she has her own imaginary classroom. She’s not scared of learning anymore. The little girl has decided that when she grows up, she’s going to be a teacher.