“Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World” at the Getty

To get us on the right track, and to convince the reader that this truly is a fine exhibition, we’ll need to start by defining what it is.

People back then ate this stuff up: “The bestiary and its imagery captured the imaginations of all types of medieval readers all over Europe, from its earliest iterations in the twelfth century well into the fifteenth century,” as assistant curator of manuscripts Larisa Grollemond writes in the accompanying catalogue (from which all of the following quotes are taken). In short, as Morrison says, “The bestiary was… the most popular nonsacred text of its day.”

Sacred or nonsacred, aren’t these old, musty pages simply repetitive, didactic, and dull?

“Like the Middle Ages as a whole,” notes Susan Crane, “the bestiaries are often thought to be intellectually static, rigorously orthodox, and committed to artistic imitation rather than innovation.” However, “Assuming that the bestiaries fit this mold flattens their puzzling incoherences, their diversity of thought, and their flights of fancy.”

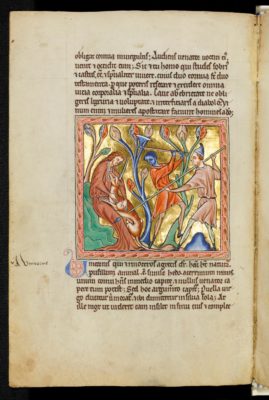

In medieval culture, the bestiary had a number of roles (sort of like a Farmers’ Almanac), packed with edifying information. At the same time, while not purporting to be scientific, the stories in the bestiary, Morrison writes, “were meant to impart knowledge and awe, and even elicit humor. As an example of the latter, here’s what the text says about the bonnacon, a creature that seems like a cross between a bull and a horse. If pursued by a hunter, “it emits a fart three acres long, using an overflow of the large intestine, a fart so hot that it scorches whatever it touches.” In this case, the hunter and his dogs.

As you can guess, we’re roughly in the same time period as “Monty Python and the Holy Grail.”

How it started; where it went

“Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World,” notes Getty director Timothy Potts, “presents the largest number of medieval bestiaries ever gathered together, representing one third of the known surviving illuminated bestiaries.”

But even the bestiaries of several hundred years ago had their antecedents, and this dates back to a Christian Greek text from around the second century AD called the “Physiologus” (or “Naturalist”), which was, as Sarah Kay points out, “a late antique Greek compilation of moralized animal lore from North Africa that gave rise to a tradition found across many languages and cultures.” And eventually, with Christological truths as a springboard, the bestiary evolved.

Evolved, and branched out: “The golden age of the medieval encyclopedia (ca. 1240-1450) followed close on the heels of the golden age of the medieval bestiary (ca. 1100-1300),” writes Emily Steiner. The encyclopedia downplayed the religious symbolism of the bestiary in its attempt to gather and organize knowledge about the world. “Although medieval encyclopedias better resemble modern information technologies,” Steiner adds, “like bestiaries they provoke wonder for Creation and praise for the Creator.”

But let’s not wander too far afield, shall we?

Bad luck for unicorns

A few bestiaries truly stand apart. The Douai bestiary, for example, because of its ingenuity of design and the elegance of the miniatures, contributes to its being, Morrison writes, “one of the most visually appealing of the Gothic bestiaries.” Of the Salvatorberg bestiary, “The animals in this manuscript often seem mischievous rather that providing any kind of moral exemplar.”

As for composition and layout, she says, “In bestiaries, the image was normally placed at the beginning of the story of each animal, as a kind of demarcation of textural divisions.” And so, apart from the bonnacon with its flamethrower-like farts, one will want to know what specific animals received pride of place in the bestiaries of old.

The most popular of the 15 was probably the elusive unicorn, and we learn that the only way to entrap it was to take a young virgin, seat her somewhere in the forest, and then wait for a unicorn to come along and place its head in her lap. At this point the hunter emerges with a lance and impales the unsuspecting creature. “Tapestries featuring unicorns are among the most celebrated artworks to survive from the Middle Ages,” Morrison informs us. What happens to the (presumably) blood-splattered maiden is not explained, nor is it revealed whether she had to seek counseling as a result of witnessing, let alone being complicit in, this gruesome murder. Today we might see the spearing of the unicorn as symbolic of Mankind’s destruction of the sacred in nature, although presumably that wasn’t the viewpoint in 1300.

Some of the other imagery given wide currency includes the pelican, piercing her own breast with her beak so that her blood can nourish her young; the tiger, whose cub has been stolen by a hunter, who tosses behind him a mirror as he flees, in which the tigress thinks she sees her offspring; the lion, breathing on its dead cubs after three days, thus bringing them to life; and the beaver, chewing off its own testicles to avoid capture. One can only guess how these tales originated, and today we’re unlikely to attribute symbolic meaning to so many specific animals. For instance, few of us think of the fox as “cunning” or the lion as “the king” of the beasts. If we do, it’s fleetingly at best, and yet these traits were an essential part of the texture of the bestiary.

Geographically, I’m not sure how widespread an area the bestiaries reached, but it seems that they were most prominent in England and then France, and to some extent in Germany and the Netherlands (taking into account that names and boundaries were different back then). Larisa Grollemond notes that “the most luxurious examples (were) produced by England during the early to mid-thirteenth century.”

But it wasn’t always just about animals. For example, “The Bestiary of Love” (ca. 1240), an adaptation by Richard de Fournival, while “no less invested in memory than other bestiaries,” writes Emma Campbell, “directs its attention to remembering something other than moral precepts.” It thus became “part of an argument to embrace love rather than resist it.”

This goes back to what Susan Crane said about the bestiaries’ “diversity of thought, and their flight of fancy.” While we can never fully enter into the mindset of these long-ago artists, we do begin to glimpse something of the milieu in which they worked at their craft and their profession. But it should be stressed that, however compelling their creations look in books or on your computer screen, there’s simply nothing like viewing them up close and in full living color. This is especially true of the gold leaf, which is dazzling in person but looks mustardy on the printed page.

It’s a world-class exhibition by any standard.

Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World is on display through August 18 at the J. Paul Getty Museum, in the Getty Center at 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles. Free; parking $15. Hours, Tuesday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., and Saturday from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. The catalogue, from which I’ve liberally quoted, is available in hardcover from Getty Publications for $60 and contains essays and catalogue entries by 26 scholars. (310) 440-7300 or visit getty.edu. ER