The original (print and online) version of this article stated that, if the bond passes, as well as State Proposition 2, then Palos Verdes Unified School District would be “earmarked” for $80 million in state matching funds.

The correct term is “eligible for,” not “earmarked.”

The $80+ million figure is according to a document given to district staff by its consultants, School Services of California, and confirmed by school boardmember Linda Reid.

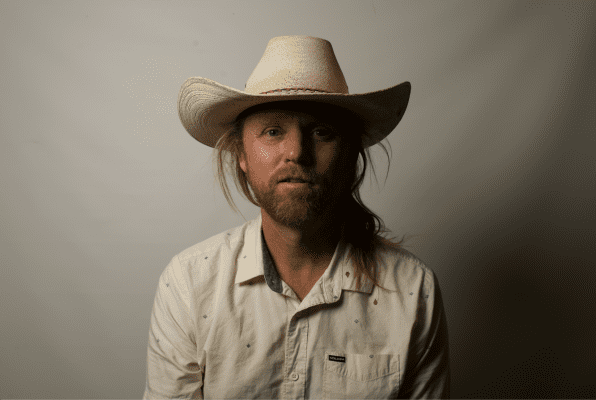

Peninsula dad Keith Murphy applies his experience launching biotech companies to helping educate voters about the need to pass school bond Measure SOS

by Garth Meyer

Keith Murphy invented a way to 3-D print human tissue. Now the father of two is helping educate voters about the Nov. 5 school facilities bond.

He became involved earlier this year when the district’s board started to give tours of the schools. Palos Verdes Unified School District has not passed a bond in 19 years. The $297 million Measure SOS on the November 5 ballot follows a failed $390 million bond in 2020.

“I thought, let me check it out and dive in deeply,” said the founder of two bioscience firms. “I realized there was a big gap in my understanding in how schools were funded.”

Among the things he learned is State funding is only for operations, such as teacher and administrator salaries, books, and basic maintenance.

“Operations and facilities are independent. Facilities were always funded by local taxes,” Murphy said.

He also learned the Palos Verdes School District ranks 48th among the 48 Los Angeles County school districts in property tax assessment, despite home values being among the highest in the County.

“Replacement and updating of major systems,” Murphy said, is the biggest need for the district’s three intermediate schools and two high schools.

“Three of the schools have electrical systems over 40 years old,” he said.

The district rents a $140,000 per month generator for Miraleste Intermediate School because a power surge melted the school’s electrical panel last year.

Murphy said school roofs, fire alarms and bell systems are similarly in need of replacement.

“It’s not every school that has these problems, but many of them do,” he said. “A lot of the schools have one or more systems past their useful lifespan.”

Funds for seismic retrofitting are also in the bond.

Murphy started a website in July to educate the community, which he named StateOfTheSchools.education.

“Money alone doesn’t fix the problem. You’ve got to put the money to the right things,” he said. “Palos Verdes voters are appropriately demanding that the district be fiscally responsible.”

Peninsula schools date back to 1964 or earlier.

The 2020 bond failed in an election that saw many other school bonds throughout the state fail.

“This kind of local funding is like oxygen for schools,” Murphy said. “The schools were built by local tax money.”

“Fiscally, I’m in the middle, or on the conservative side. Part of the problem, I think, is from 2010 to 2020, they weren’t asking for anything, They should be doing that regularly. To be running moderate bonds every four to five years years, rather than nothing for 19 years, then a big one.”

Is it time for an old-fashioned barn-raising on the hill?

“Generally speaking, the buildings are in good enough condition,” he said.

Murphy has lived in Palos Verdes since 2012.

If the bond passes, the district also becomes eligible for state matching funds. A statewide bond – Proposition 2 – is on the Nov. 5 ballot as well, to add to this funding. It would spread $10 billion around California, including $80 million+ of it eligible to go to Palos Verdes.

Peninsula Assemblyman Al Muratsuchi (D-Torrance) was one of the proposition’s sponsors.

Palos Verdes Unified School District serves 11,000 students across the four cities on the Peninsula.

The school board voted unanimously in June to put the bond on the ballot. To pass, it needs a “yes” from 55% of voters.

The items that would be funded add up to a nine-page list, by school, including repair or replacement of leaky roofs; electrical systems, sewer and gas pipes, restrooms, classroom repairs, replacing old and inefficient heating and air-conditioning systems, taking out asbestos and lead, new portable classrooms, seismic improvements, campus security and updating science labs.

“We don’t have to do everything on this list. But we can only do things that are on the list,” Murphy said.

Cost to taxpayers would be $29 per $100,000 of assessed value, or about $300 per year for an average homeowner in the district.

The last Palos Verdes bonds were passed in 2000, then two, 25-year bonds in 2005 – which taxpayers will pay on until 2034.

“(The new bond) is like a replacement tax, comparable to what we paid before,” Murphy said.

Degree of difficulty

In 2007, Murphy founded Organovo, which pioneered 3-D printing of tissues that mimic traits of human tissue. In 2017, he founded Viscient Biosciences, which uses diseased cells from humans to help develop drugs that fight diseases.

So what is the difference between what Murphy does by day and his effort to inform local voters about the Palos Verdes school bond?

“This is a lot harder,” he said of the latter. “I didn’t anticipate the challenges of getting information out to a lot of folks. Everyone has certain assumptions. None of it was what I expected either.

Why am I doing it? Honestly, I feel like I can help, so I really want to.”

School board member Linda Reid

Linda Reid, is 10-year member Palos Verdes Unified School Board.

“The nature of schools is, you can’t repair facilities without a bond,” she said. “It’s a terrible system, but it’s what we have. For how beautiful our community is, our schools are in really bad shape.”

Reid was on the board when it ran the 2020 bond, a $390 million package at $38 per $100,000 in assessed property value.

Compared to the 2024 version, it covered more items, more comprehensively.

“(The new bond) is just really basic stuff,” Reid said. “To have just the most egregious, terrible things repaired first.”

She said the list goes beyond what the bond would actually cover, if passed.

“We won’t get to everything on this list. There won’t be enough money,” Reid said. “There is a high probability of that being the case. It’s impossible to predict economies of scale for particular projects, cost increases for materials, etc.”

“The new list is prioritized by biggest need,” said Reid, whose two children went through Peninsula schools, graduating in 2016 and 2020. “I’ve seen this stuff getting worse and worse over the years.”

Why wasn’t there a bond run between 2005 and 2020?

Reid joined the board in 2015.

“It’s hard to say,” she said. “In retrospect, perhaps that board should have, but our community is tax-averse… and in 2020, we just thought, across the board, people will support the schools. That was probably naive.”

“We’re hoping this will unify the community to support it,” she said.

Reid has lived in Palos Verdes Estates since 2001.

“Our board; we don’t agree on much of anything, but we’re all in support of this.”

Devin Serrano, new superintendent

Superintendent Devin Serrano joined the Palos Verdes district last summer.

“For me, as a first-year superintendent, it was the last thing on my mind to be running a bond, but it became the first priority pretty quickly,” Serrano said.

She named parts of the bond’s list as standouts – replacement of portable classrooms over 30 years old, for one.

“They are supposed to be 10-year structures,” she said. “They’re beyond repairing.”

Serrano noted that last year, the school district counted 45 leaking roofs over classrooms, and that the bond is needed to replace each of the district school’s all-original windows.

“Our schools look okay from the outside, from the curb, but once you get inside… Every school has something (on the list),” Serrano said.

The projects are only at the school buildings, none at the district office, “or any place we’re not currently serving students,” Serrano said.

The process to put forth the new bond began last November with the school board, leading to six informational meetings and the tours.

Serrano noted the electrical incident at Miraleste.

“Our schools are in such disrepair,” she said, “We can’t wait another two years.” PEN