A trip to Africa by two MB police officers connects communities across the world

by Mark McDermott

One day in 1995, a 13-year-old girl named Nneka walked from her family’s home in the Nigerian village of Amuyi to a nearby body of water that was part pond, part muddy ditch. She and her 11-year-old brother Emeka were fetching water for their family.

Amuyi was one of a network of 10 villages collectively known as the town of Nsude that relied on this dingy brown, man-made water reservoir for their drinking and washing needs. None of the villages had running water. All they had was this dank, standing water, which built up during the rainy season, reaching roughly 30 feet deep.

Nneka and Emeka were going back and forth, tag-team style, bringing buckets of water for their home. But at one point, as he circled back to the water, Emeka realized something was wrong. His sister’s bucket was floating in the water. She was nowhere in sight. He began screaming.

“People came out, and those who knew how to swim jumped in,” said Joseph Udeoji, Nneka’s younger brother, who was 8 years old at the time. “I remember seeing my mama standing on the edge of the water screaming, just helpless. People jumped in, but it was muddy. It wasn’t like a clean pool of water, so you couldn’t really see. Nobody could see where her body was.”

Finally, somebody found Nneka, and pulled her to the shore.

“People were slapping her face, saying ‘Wake up! Wake up!” Udeoji recalled.

Nobody in the village knew CPR, nor were there any doctors. The family took Nneka’s limp body to her father’s shuttle bus — Joseph Sr. was a school principal and a farmer, and ran a transport business, whatever it took to put food on the table. They drove Nneka to the nearest hospital, 30 minutes away.

“Less than an hour and a half later, they brought her back,” Udeoji said. “And everybody knew it was done.”

Nneka had been the only girl among four boys and had served like a second mother within the family, helping her mother Christiana with everything. She’d been a buoyant presence, an athletic girl who ran track and always had a smile on her face. One slip in the mud, and this vibrant girl was gone.

Udeoji would never forget his family’s feeling of helplessness.

The very next year, the family received some much-needed good news. An uncle who lived in the United States had entered the family in a visa lottery, successfully. The Udeoji family — four boys, their parents, and a cousin — flew to Los Angeles and began a new life.

The Nigerian diaspora in America are among the most successful immigrant groups in the world, largely because of the huge emphasis they place on education. According to the Migration Policy Institute, Nigerians are the most educated immigrant group in the U.S., with 61 percent attaining at least a bachelor’s degree (compared to 31 percent of the total foreign-born population and 32 percent of the U.S.-born population).

Joe Udeoji arrived not speaking a word of English, but within a dozen years had earned a bachelor’s in health science and a masters degree in public health. The loss of his sister’s life continued to animate his own. His drive was to help others. He entered a career in law enforcement.

Three decades later, Joe Udeoji was at work — he is now a detective for the Manhattan Beach Police Department — and was showing photographs of his home village to a colleague, Lt. Steve Kitsios.

Six years ago, Udeoji founded a non-profit called the Peoples Naija Foundation, to provide basic preventative health measures. He goes back to Nsude every December to help lead a health fair at which people receive basic dental care, and are instructed in life-saving measures such as CPR.

Nneka is the foundation’s guiding spirit. If something like it had existed at the time she fell into the ditch, she very well might be alive today.

“One hundred percent, my sister might still be with us,” Udeoji said. “In drowning incidents, with just a little quick CPR, and get that person to a good hospital, they are able to pull through. I feel like she probably had a lot of water sitting on her lungs, and with a chest compression we would have been able to give her a fighting chance, at a minimum.”

Nigeria, though fantastically rich in natural resources, has long been plagued by one of the most notoriously corrupt governmental systems in the world. Like many post-colonial nations, there exists an extremely wealthy elite and a teeming population of poor people, with almost nothing in between. What it means for people in villages like Amuyi is few basic services, much less preventative health care.

“I love my country, but it seems like nothing works,” Udeoji said. “No systems. There is no ambulance system that you are going to call 911. If you call an ambulance, they are going to say, we’ll see you in two or three days. You have to pay the police department just to come do what they are supposed to do. You don’t have those resources, so that’s why everybody has to do things locally, within themselves.”

When Udeoji began the Peoples Naija Foundation, it was based on this — giving the village the tools to help itself, such as CPR training, and basic medical supplies. The foundation’s annual health fair has grown every year since beginning in 2018.

“We host a medical outreach, where we bring in specialists — doctors, optometrists, dentists and multiple nurses, and we’ll bring it to different villages,” Udeoji said. “We offer free health care for that day, and it’s crazy how something small can be so big. You have people who come in who feel they are going blind, and you give them a little eye drop and some 99-cent reading glasses that we take for granted here and they think we are doing miracles. They can see again. That pressure they had on their eyes, they don’t have it anymore. Or you have somebody who has been having a tooth ache for two years, creating other diseases of the mouth — the dentist can pull one tooth, just one tooth, and the people have major relief. That is the kind of small scale stuff we’ve been doing. The community loves it and they have benefited a lot from it, and that is why we keep doing it.”

“I just saw an opportunity,” Udeoji said. “I am not in the business of building a hospital or managing anything that huge in scale. We give people the basic, necessary things, which is education and access.”

Kitsios was looking at the photos from one of those trips and noticed something odd.

“Why does everybody have a bucket in their hands?” Kitsios asked. “Every person I see has a bucket.”

“They are going to get water,” Udeoji replied.

Kitsios was dumbfounded. He was born in a village in Greece, and has traveled to 27 countries. But he had not experienced life without running water. Kitsios, like Udeoji, and like most people who have dedicated their lives as first responders, had an instinctual urge to help.

“Dude, can I go to Africa with you one day?” he asked.

Of course, Udeoji said. You can come with us this year. And as they began talking further about it, they had several ideas. One was to bring bags of rice. In a village where most people make $25 or $30 a month, a big bag of rice is a huge boost.

“And so after talking, we both were kind of like, ‘Let’s do the rice, let’s do the education and the medical outreach that you’ve been doing these last several years. But let’s get a water well there, you know?’” Kitsios said.

They researched it and discovered that in order to make a well in Udeoji’s village, they’d have to drill 730 ft. deep. It would cost $25,000.

“At first it was kind of like there’s no way, $25,000 is a lot of money,” Kitsios said. “But with the support from the community in Manhattan Beach, the people that we’ve met over the years, we now have a good mission to fulfill — to get water to Joe’s village.”

Joe Udeoji with the leader of his foundation’s medical staff, Nonso Anene, at the pharmacy section of the annual Health Fair the non-profit holds in Nigeria each December.Journey into America

Udeoji’s first memory of the United States was of a land of lights.

He and his family arrived at LAX at night. He’d never been in an airplane before, so that experience in itself filled him with awe.

“I remember coming out of the LAX baggage claim and having a whole group of family and friends waiting at the airport to welcome us,” he said. “And I remember just being in a car, my uncle was driving, and all I saw was lights, this city with lights everywhere. And the road just moved — in Nigeria, any regular road, it’s like off-road. And I remember my uncle’s statement, ‘Welcome to Udeoji family,’ just basically saying, ‘Welcome home.’”

An even bigger reception awaited them at Udeoji’s uncle’s home. But within days, it was time to get to work. The idea had been suggested to them that they split up and stay with different family members and friends, but the Udeojis would always stay together. The family rented a two bedroom house in LA that they shared with a stranger.

“We shared that house, believe it or not, with an older white man,” Udeoji said. “That was my first encounter with anybody other than a black person, and this man was so nice. His name was Mr. Jones, and we lived in LA. One of the other things I remember is my uncles wanted to split us up, just so we could each have a little bit of space, and my mom fought and fought so that would not happen. She said she would get a job immediately and do whatever she needed to do to keep our family together. And that’s part of the reason why we are still as tight as we are now. We all still grew up together. We went through the struggles of assimilating to a new culture, and we got through it, together.”

His father had health issues that he was finally able to get treated for, but was unable to work. Udeoji’s eldest brother and his mother obtained jobs and provided for the family in those first years. Udeoji attended Horace Mann Junior High. He realized immediately that he would need to use every moment of every day in learning how to adapt.

“You do what you can. And I tell you one thing, once you are put in a situation, you have to survive, and your brain tends to adapt to it,” he said. “You learn fast. I got into a few fights with people making fun of me. I had to use sign language to demonstrate what I was trying to say. I had to go to school an hour early for English class. I learned how to communicate within eight months, because I had no choice. And the bullying didn’t last too long, because I was ready to fight at any time.”

The next year, the family moved to Inglewood, where Udeoji attended Crozier Middle School and then George Washington Preparatory High School.

“I went to one of the worst high schools you can think of, at that time,” he said. “Do not let the word ‘prep’ fool you. It was not preparatory.”

Udeoji excelled in school, regardless. From the time he arrived, he was utterly focused on learning.

“Every moment counted for something,” Udeoji said. “I didn’t really have lunch, because I was doing too much — I was in a class trying to learn something, or somebody was trying to tutor me. It teaches you focus and discipline. It also teaches you self-confidence, because you have to rely on yourself. Some of the things I do now, on this job [as a police officer], it doesn’t faze you too much, even as a cop. Because for me, I’ve dealt with so much. It’s not that I had a hard life. I did not. Our family always had three square meals, we always had clothes and things. I didn’t struggle to eat, ever, even back home. My parents made sure of that. But it does teach you to go through these obstacles in life, and it makes you who you are. It gives you the life experience that you need to deal with a lot of situations.”

His family stressed the importance of education, and when he thought back to Nigeria, he felt a responsibility to do well. Nigerians, Udeoji said, think of everywhere in the outside world, be it London or Los Angeles or anywhere in between, as a sort of fabled promised land. All of that rich world is known by a single word.

“Overseas,” Udeoji said. “Every place is overseas …. For many people, especially in African countries, coming here is a second heaven. People would do anything to come here. People truly think of money growing on trees.”

“And so, most people who get an opportunity to come here do not want to let anybody down, or don’t want to be seen as a failure. Education is one thing that people preach back home as a way forward….So for me, I knew that was one thing I could not slack on. I definitely made sure I was focused on education.”

The other thing that Udeoji was drawn to was sports. Amid all the pressure, he found freedom on the basketball court, and comradery.

“One of my favorite things was being part of a team, and having a purpose,” he said. “It gave me something to look forward to, something to work on, another kind of skill set. Sports was my way out.”

Udeoji attended San Jose State and made the basketball team as a walk-on. After earning his degree in health sciences, he went to work for a children’s hospital for two years, and after that made a brief attempt to play basketball professionally. All the while, the idea of the foundation was beginning to grow in his mind. He went back to school, obtaining his master’s in public health at California State University Long Beach. Within a month of graduating, he was hired by the Hawthorne Police Department, and entered the police academy.

If it seems counterintuitive that someone passionate about public health was drawn to law enforcement, for Udeoji, it made perfect sense. Law enforcement and public health are about serving a larger good.

In Nigeria, the police are known for their corruption, but Udeoji had an uncle who was revered, ironically, because he died poor after a long career as a policeman.

“People used to say he’s one of those very few police officers who died poor,” he said. “A lot of our family members said the reason he died poor is he never took a bribe, ever, and what you make on a monthly basis as a police officer in Nigeria is never enough to sustain yourself. So as much as people could look at it in a bad way, his story stuck with me, because he did it the right way.”

Coming of age in the United States, Udeoji saw how many of his friends were terrified of the police. This was before the Black Lives Matter movement, but in places like Inglewood, the reasons that caused that movement were viscerally present for any young black man. Though he never had an incident himself, nearly all Udeoji’s friends had been pulled over for the color of their skin.

He became a police officer because he wanted to combine those two things — to do things the right way, and in so doing serve the public good.

“I wanted to go into law enforcement to be part of the change,” Udeoji said. “I wanted every encounter with me to be a positive encounter. Even if I take you to jail, I wanted it to be a positive encounter. If I stop you and give you a ticket, or if I don’t give you a ticket, I want that to be a positive encounter. Even if I write you a ticket, I’m going to make a joke, or I’m going to take time to explain something to you. Honestly, I’ve made it a personal goal to make sure that every single stop that I do, I leave that person with something positive, regardless what it is.”

MBPD Det. Joe Udeoji, far left, with the “Igwe,” or leader, of the township of Nsude, Nigeria. Udeoji is pictured with his brother Chris and mother Christiana. The family, through its Peoples Naija Foundation, has held medical outreach fairs in their home village for the last seven years. Photo courtesy PNF

Peace officers

Udeoji has been reluctant to bring attention to the work he and his family are doing with the Peoples Naija Foundation. Though he is the president of the foundation, he has rarely done much by way of fundraising. Much of what the foundation has achieved has been through his own family’s contributions.

“It is not the way I was raised,” he said. “I do not beg for things…But I got over it. Because none of this money is going to be misused. Everything is going to be given to enhance somebody’s quality of life.”

MBPD Chief Rachel Johnson said Udeoji trains other officers, and is a strong, calming presence within the police force. But few people know in much detail the work he has been doing in Nigeria.

“Some people know he goes back to Nigeria, that he helps and obviously that’s thought of very highly,” Johnson said. “But Joe is not a self promoter. If you talk to Joe, you hear about what he’s doing, but Joe is not one to have his hand out. He’s just been quietly talking about this….He’s a quiet leader and he tries to let his work speak for itself.”

Kitsios had been aware of the foundation for years but when he learned about the water situation — and Udeoji’s hopes to address the problem — it hit home. The two officers talked about it after a 9 p.m. briefing at the department. Then Kitsios made an immediate fundraising call to an acquaintance. At 4:30 the next morning, the two officers met Kitsio’s friend at a Starbuck’s to collect a check. This year’s mission to bring water to Udeoji’s village was off and running.

“Steve has a big heart, and he wears his heart on his shoulders,” Udeoji said. “You can see it. He cares about his officers. And I am not even talking about this project at all, just the way he goes about things. He cares about his people.”

Kitsios said the friend he called was Eddie Braun, a Hollywood stuntman who lives locally and completed a similar mission to Africa to do a water project with the actor Charlie Sheen.

“Eddie gave us a little brief about how he did it,” Kitsios said. “And then he wrote a check for $10,000.

Mayor Amy Howorth learned of the project just this week. She was both astonished and somehow unsurprised, because she has noticed over the years how members of the police and fire departments tend to serve others even when they are off duty.

“When I think of our first responders, our police and fire departments, and the women and men who work in those departments — they got into their careers to help people,” Howorth said. “They try to keep the peace. They try to prevent fires. And what you will notice is they are constantly doing fundraisers for this or that, but never for themselves. They are constantly doing things to help others.”

Howorth said that five years ago, as a member of Leadership Manhattan, Kitsios led the effort to install defibrillators in MBPD patrol cars.

“He pointed out to all of us that police often are at the scene before fire. So they need to have those defibrillators as well,” Howorth said. “He was thinking about how he can help people statewide, and then he put his money where his mouth is, and raised a bunch of money to do it. So he’s that guy….Kitsios has the world’s biggest heart.”

Kitsios traces his involvement with this project to a near-tragedy his own family experienced when his wife was diagnosed with breast cancer.

“She’s been good now for seven years, and I remember being so grateful that she survived, unlike the hundreds of thousands of women who don’t survive,” Kitsios said. “I was very grateful to the City for the way they treated me, and for the insurance that they provide. I was grateful that my wife was alive and that my daughter still had a mom. I promised myself, and God, I will do better. I will be better. So I try to do something, and be a good guy every day. This is something that will save lives, and people will be grateful for it. This trip means a lot to me.”

Udeoji and his wife, who is also part of the project, have two little girls. He says the foundation honors his sister’s memory, but he hopes that through his daughters, it will also one day be part of his own legacy.

“The way Nigerian culture is [emphasizes] what you will one day leave behind,” he said. “So part of me has such a passion for this, but it is also something that I will leave behind.”

The Prayer of St. Francis of Assisi, also known as the prayer of peace, has a line that resonates beyond what religion one does or does not believe in. “It is through giving,” the prayer says, “that we receive.”

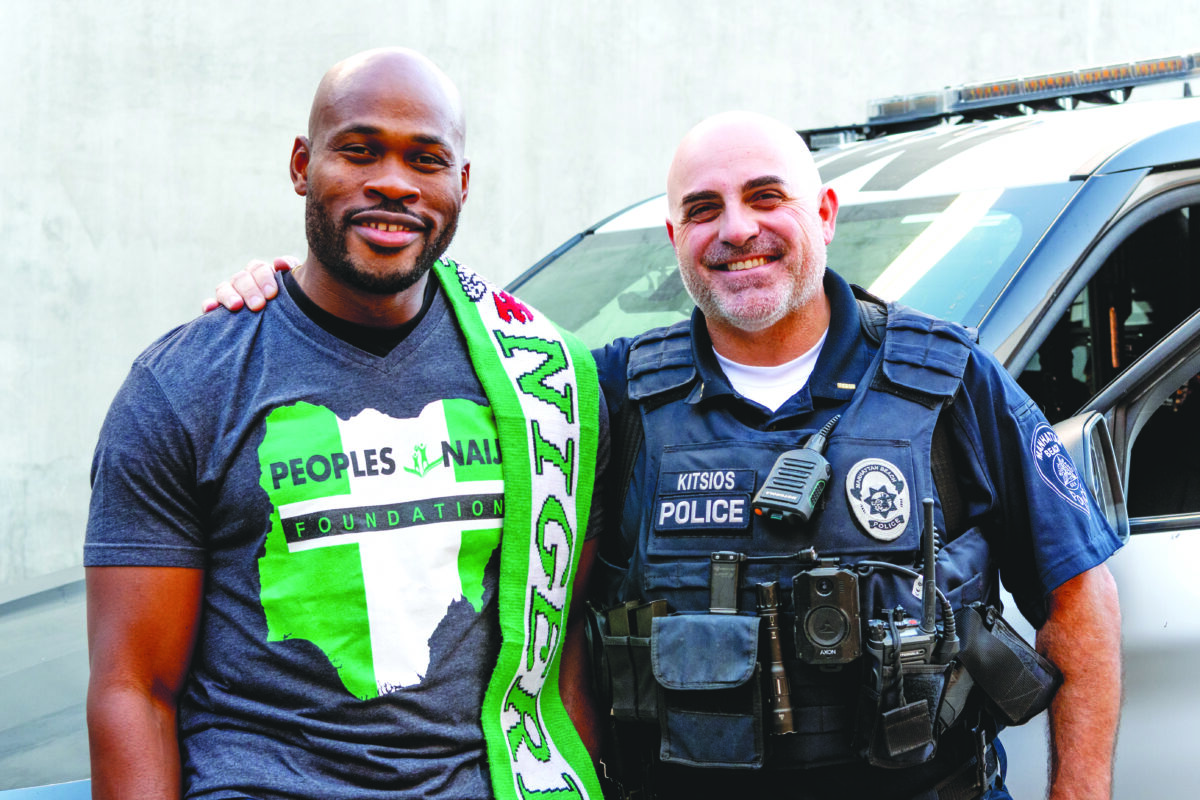

Manhattan Beach Police Department Det. Joseph Udeoji and Lt. Steve Kitsios. Photo by Kenny Ingle

Mayor Howorth said that in this season of Thanksgiving, the project Udeoji, his family and colleague are leading in Nigeria is a reminder of how important the simple things in life are.

“What they are doing is allowing us to realize how fortunate we are, and that it is incumbent upon us to help others, whether they are next door or across the world,” Howorth said.

Udeoji’s wife, Amaka, has a message in her bio on the Peoples Naija Foundation website that touches on this same thought.

“We are all a part of one another,” she wrote. “No matter which continent you are from, what race, what gender, or what social class you belong to, we are all connected.”

Those connections can be hard to see at times. But through the foundation, the untimely passing of a young girl in a Nigerian village 29 years ago has created a connection between Manhattan Beach and that village. It is a connection that will likely continue to grow. The foundation hopes to build this one well, which will give water to almost 20,000 people, as the first of several wells to bring more water to more people.

This is all happening because Nneka has not been forgotten.

“We remember people who have passed on before us by continuing to talk about them,” Chief Johnson said. “This gives Joe the opportunity to continue to talk about her, to honor her, and to at least try to help make sure no one else suffers the same fate for the same reason.”

Johnson is particularly struck by what a simple, powerful gift CPR training is for Udeoji’s village.

“These are things that we take for granted,” she said. “There are so many other places where it’s more vital to know CPR. Here, even if I didn’t know CPR, and a person went down, surely someone is going to come along in the next moment or two who knows CPR, and we have very quick access to fire trucks and ambulances for that lifesaving care. But you go to Nigeria and to Joe’s village where that’s not the case.”

Kitsios and Udeoji will leave for Africa on Christmas day.

“When Steve comes to Nigeria, I think he will be humbled to see, regardless of the conditions we are talking about in all of my community, how happy people are, how joyful people are at the end of the day,” Udeoji said.

“They find ways to make it work. They find ways to make it happen. But just know that a little bit of help, the small things we are going to do this December, are going to be major for that community, and it will be talked about for a long time. My goal is not to stop there. My goal is to continue to find other avenues, other ventures that we can do to improve that community.”

Kitsios has a quote that hangs in his office at the police station. “To live a life of service,” it says, “is to live honorably”

“That goes for my police job,” he said. “And it goes for what we are doing here.”

For more information see peoplesnaija.org/, or contact Lt. Steve Kitsios at skitsios@manhattanbeach.gov, or Officer Joe Udeoji at judeoji@manhattanbeach.gov.