First this way, and then that

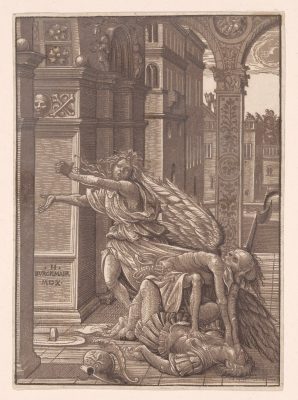

“Lines of Connection: Drawing and Printmaking, 1400-1850”

by Bondo Wyszpolski

So what exactly are we talking about? Reading the accompanying catalogue may help:

“According to conventional definitions, a drawing is typically considered a unique object and is the product of marks directly made by hand on the surface of the support. These marks can be either executed in chalk, ink, or other materials, or impressed into the sheet with an implement like a blind stylus. By contrast, a print is a work produced by the transfer of medium or of a design from one surface to another by means of pressure. This transfer entails a reversal: when printed, the design laid out on the matrix is flipped, producing its mirror image on the receiving surface.”

That’s a bit much to digest, I know.

The exhibition is curated by Edina Adam, assistant curator of drawings at the Getty Museum, and Jamie Gabbarelli, associate curator of prints and drawings at the Institute of Chicago. They’ve divided their subject into four parts or themes: Drawings for Prints: Model Behavior; Prints After Drawings: To Collect and Train; Drawings After Prints: To Imitate, Emulate, and Substitute; and Hybrids: Pushing Against Boundaries.

This equates to a word-for-word and, when that falls short, the sense-by-sense approach, “to preserve the original’s meaning and intention.” For example, if a punchline in one language doesn’t compute in another, the translator comes up with a comparable example for the audience he’s translating for.

Among the terms you’ll be introduced to is “modelli,” which means “drawings that were created to be made into prints.” And then there are “prints made after drawings that were not preparatory,” and “drawings made after prints.”

Now let’s say you’re a collector. What should you be on the lookout for? “The major features of collections of prints after drawings (are) technical ingenuity, a concern for formal correspondence, an interest in function and historical context, and the importance of provenance.”

I’ve added those few lines because the catalogue gets quite detailed and I sincerely doubt that the layman is going to easily grasp the intricacies of Mary Broadway’s essay about Jean-Antoine Watteau’s “The Old Savoyard” and Boucher’s etching of it. The collector, on the other hand, may. This brief essay is actually one of five “Spotlights,” which are highly specialized investigations into the works of Peter Paul Rubens and Paulus Pontius, Anton Möller, Giovanni Benedito Castiglioni, and William Blake, in addition to Watteau.

There’s a long essay by co-curator Gabbarelli on hybrids, which notes that “By their very nature, hybrid works on paper will always defy neat categorization.” Furthermore, “The interpretative instability that runs through hybrid works… sits at the heart of their aesthetic and intellectual appeal.” This is like the “And Other” bin in a record store: things that aren’t pop or jazz or classical or holiday music. But so often that’s where the most interesting stuff is to be found.

In addition to the few artists I’ve mentioned, the catalogue also contains discussions about works by Francesco Panini, Maria Sibylla Merian, Henry Fuseli, Thomas Gainsborough, Hendrick Goltzius, and more. In particular, I liked the monotypes by Castiglione, whose work I’d never before encountered.

It’s fair to ask what I, personally, got out of reading the catalogue, to which I can answer: Not much. Of course I didn’t know that, going in. But what did impress me from the start was the layout and the artwork that was featured, the whole package, as it were, and all of it beautifully done.

Lines of Connection: Drawing and Printmaking is on view through Sept. 14 at the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles. Hours, Tuesday through Sunday from 10 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. and Saturday from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Free, but reservations required. Parking is $25 ($15 after 3 p.m.). Call (310) 440-7300 or visit getty.edu. ER