Stephen P. Hinshaw grew up in an idyllic, Midwestern town. His father was a brilliant philosopher who studied with Albert Einstein and Bertrand Russell before becoming a professor at Ohio State, where his mother also taught. The family had 50-yard line seats to the Ohio State football games, enjoyed backyard barbecues and celebrated all the milestones of family life.

But their seemingly perfect 1950s suburban existence was not what it seemed. As a child, Hinshaw noticed that his father Virgil would often disappear without warning for months, even years at a time, often missing seminal moments in his son’s and daughter’s lives and leaving his mother with the responsibility of raising the family.

“One day dad was there, and the next he wasn’t,” Hinshaw said. “It was a mystery, but underneath that was terror…our lives as a family were bipolar lives. Life was great, or it was awful. There was the warmth of dad being there, or there was nothing.”

In his new book, “Another Kind of Madness: A Journey Through the Stigma and Hope of Mental Illness,” Hinshaw, a professor of psychology at UC Berkeley, recounts his father’s battle with manic depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and the impact it had on his family.

There was the time Hinshaw and his sister Sally, both toddlers, were asleep upstairs while his parents watched a show on the black and white, family TV. His father became convinced the singer was sending him messages and insisted he and his wife drive to the station in Cincinnati, 130 miles away. His mother had two choices: let him drive off, maybe never to see him again, or go along and pray that he came to his senses. They drove 80 mph on country roads late at night only to get to the station and find it closed. His mother convinced his dad to turn around so they could make sure the children, who were left alone, were okay.

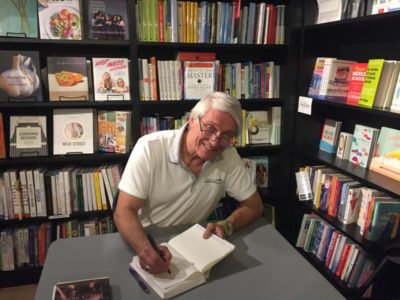

“Luckily, we were asleep and nothing happened,” Hinshaw told a group gathered at Pages bookstore for a reading of his memoir last month. “We could have have fallen down the stairs or Child Services could have come and taken us away.”

While interviewing relatives for his book, Hinshaw learned of another incident in 1936 when a delusional 16-year-old Virgil claimed he could save the world from the Nazis by jumping off the roof of his family’s Pasadena home. He survived the jump, but spent six months in a mental hospital.

None of that was ever discussed in the home and his father’s absences were never explained to Hinshaw, who, despite the silence, tried to find out where his father had gone.

“First grade had ended. I noticed that dad wasn’t home. The air outside was warm, the pavement baking in the noonday sun. I asked once or twice but mom said that he’d return from his trip pretty soon, maybe a few more weeks. What trip? I inquired as softly as I could, but she said nothing more. It wasn’t the first time this happened; it wouldn’t be the last,” he wrote in his book.

What Hinshaw and his sister didn’t know what that their father was sent off to barbaric state mental hospitals following bouts of wild, uncontrollable behavior followed by serious depression. His father’s lead psychiatrist had sworn the family to silence: “Don’t ever tell your children about this. They’ll be permanently destroyed.”

His father followed the doctor’s orders and waited until Hinshaw was an adult to share his struggles with mental illness. “It wasn’t until I returned home for my first spring break in college that my father started to tell me of his life,” Hinshaw said. “We had three to four talks a year for the next 25 years.”

“It gave me a kind of path, a mission,” he said. “There was so much to learn about brains and families and development and mental illness.”

But while studying psychology, he was too embarrassed to talk about his father’s illness, even though he was learning to perform clinical evaluations for the very illnesses his father battled.

“The stigma had been inside of me as well. I was ashamed,” Hinshaw said. “I was worried that I would be next and that his genes would be transmitted to me.”

When he started to tell a few people about his father’s illness, they wanted to know more. It was a liberating, but he also realized that while the public knows more about schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, the attitudes about these illnesses have remained much the same as they did in the 1950s.

Hinshaw is committed to overcoming the stigma and silence of mental illness by sharing his family’s story.

“If we don’t solve this stigma we’re not going to get anywhere. People with mental illness can get a lot better, but they need to be in treatment,” he said. “We don’t need more statistics. We need stories, the everyday stories of coping and heroism. That’s what’s changed the minds on cancer, and I think that’s what’s going to change minds on mental health.”

“Another Kind of Madness: A Journey Through the Stigma and Hope of Mental Illness” (St. Martin’s Press, $26.99, 271 pages)