As unmanned aerial vehicles gain prevalence in the skies, South Bay residents and officials — like everyone else — must deal with unprecedented issues of privacy and safety

On July 4, Hermosa Beach Police Chief Sharon Papa was conducting roll call at the station when a loud boom sounded from City Hall. A small camera-equipped drone, or unmanned aerial device, had crashed in the atrium, and no one was there to claim it.

“At first my thought was, ‘Was someone trying to spy on the police?’” Papa recalled.

She was relieved when surveillance footage showed that the culprits had been just a couple of harmless kids. She recounts the incident with ease but acknowledges that the situation could have been more dire.

In El Segundo, the Chevron refinery has recently documented three separate incidents wherein a small drone trespassed onto its property and proceeded to circle around equipment and infrastructure. Refinery staff called police on one occasion, but without a city ordinance mandating how the technology’s use can be curtailed, they couldn’t deter the drone controller, let alone charge him with a crime.

Joe Caravello, the refinery’s emergency-response team lead, urged the El Segundo City Council earlier this month to ban drones or regulate them, as an accident at the refinery, which processes 274,000 gallons of transportation fuel every day, would directly impact the surrounding communities.

“A lot of drone operators don’t understand what they’re doing when they fly into a refinery and what the risk is,” Caravello said. “They could also become a major distraction when work is going on, but the biggest thing is security. … There are some very bad people out there that would like that info and can use it to hurt the refinery.”

Unmanned aerial vehicles are on the rise in U.S. airspace. The Federal Aviation Administration, which regulates them, estimates that at least 30,000 drones will be airborne across the country by 2024.

One report estimates $6.4 billion is currently spent annually to develop drone technology around the world. In 10 years, that number is expected to nearly double.

And domestically, the industry is expected to create 100,000 new jobs during that time, while adding $82 billion to the economy, according to the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International, a Virginia-based trade group.

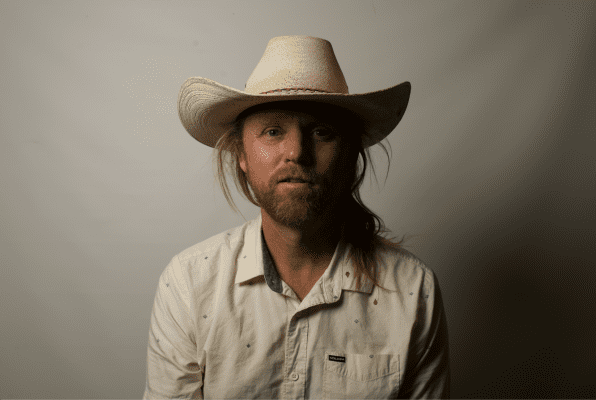

“The fact that you can order it online, take it out of the box and fly it, it could end up in anyone’s hands,” said Bo Bridges, a Manhattan Beach-based photographer who purchased his first drone in 2010.

Bridges, who previously shot for ESPN’s X Games, now owns three drones and uses them to shoot surfers and bikers, but he doesn’t anticipate using those photos professionally until the drone’s built-in camera technology improves, he said.

Aside from recreational use, drones, which vary widely in cost and specifications, have show usefulness across a spectrum of uses.

The FAA requires approval for drones weighing more than 55 pounds. So far it has certified more than 600 public-sector entities to fly drones, largely law enforcement agencies and universities. U.S. Customs and Border Protection flies 10 unarmed Predator drones to patrol the borders for smugglers and trespassers. Other agencies use drones to survey disasters, fires, hostage situations and more.

Commercial use is currently outlawed by the FAA, although the agency’s authority has been in question.

Last month, Amazon wrote a letter to the FAA seeking exemption for its PrimeAir program, which banks on delivering items via drones to customers within a half-hour. On its website, the Seattle-based company says it anticipates the delivery option to be available as early as next year.

Because civilian use of drones is unprecedented, laws governing its use are still murky. Papa said her department has fielded a few complaints about a drone lurking on the beach or by someone’s window. Yet there’s not much police can enforce, as no municipal code regulates the use of drones. Hermosa Beach, like many others, is waiting for federal and state laws to crystallize before trying to regulate them.

“It’s one of those evolving areas of the law,” Papa said, “so we’re still looking at it along with everyone else as a society.”

DETERMINING LEGALITY

While the FAA asserts that commercial drone flights are currently illegal without its case-by-case review for approval, a judge’s ruling in March has placed the agency’s authority in question.

An administrative law judge threw out the FAA’s citation against Raphael Parker, who was fined $10,000 in 2011 for using a small drone to shoot a promotional video at the University of Virginia. Patrick Geraghty, a judge with the National Transportation Safety Board, ruled that small commercial drones should be treated as model aircraft, which are self-governed by 1981 guidelines. The FAA has appealed the decision.

Under Congress’ FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012, the agency has until next September to write regulations that will safely integrate commercial drones in the airspace.

The deadline likely won’t be met; an FAA administrator told a Senate hearing in January that the agency plans to phase in different drone operations over a longer period.

According to reports, President Barack Obama will soon issue an executive order to develop privacy guidelines for commercial drones.

LACKING PRECEDENT

After several purported wrongful arrests in the early 2000s, Torrance resident Daniel Saulmon began filming local police activities with a handheld camera and posting them on his YouTube channel under the alias Tom Zebra.

About six months ago, he upgraded his gear to the DJI Phantom Vision+, a $1,400 camera-equipped drone weighing less than 3 pounds. He said it’s no substitute for a handheld camera.

“The idea was, with a drone I can stand in a location where I wouldn’t be subjected to hostile police and threatened with arrest – I could fly closer while staying at a safe distance,” he said. “The reality is I couldn’t spy on you with this thing if I wanted to. The lens is really wide angle. There’s a lot of hype, but it’s hype more than anything else.”

On Aug. 6, Saulmon was at the Port of Los Angeles in San Pedro, taking aerial shots of the USS Iowa as part of an annual summer event called Navy Days.

His drone had been in the air for about 10 minutes when two Port police officers asked him to land it. They seized the gear and cited him under an L.A. municipal code that prohibits flying “any balloon inflated [with flammable material], helicopter, parakeet, hang glider, aircraft or powered models thereof” at a city park or city-owned harbors.

This is the first time Saulmon said he’s been cited under the code. In the past, police have advised him against flying in crowded areas or over their headquarters.

Other times, they are curious about the apparatus and “hit [me] with a million questions,” Saulmon said.

Last Wednesday, he learned at the courthouse that port police missed the deadline to file charges. When he returned to the police station, they refused to return his property, he said.

“They informed me that they were still filing charges, so they changed the court date to sometime next month,” he said.

He plans to appeal if he is charged. “The First Amendment protects my right to take pictures,” Saulmon said. “Photography is not a crime.”

Carey Fujita, another Torrance resident and drone flier, said almost the same thing happened to him at Navy Days, but the port police did file charges with the District Attorney’s Office.

He said he’s flown his DJI Phantom Vision+ at the port numerous times before, and an officer once told him merely not to fly too close to the ship.

“It bummed me out that they didn’t give me a warning,” said Fujita, who shares videos on YouTube under the alias South Bay Drones and operates riseofthedrones.net.

At the courthouse last Wednesday, however, the prosecutor told Fujita she had never arraigned a drone case before and postponed it for next month.

“They didn’t know how to deal with it,” he said. “… She wanted to go back and do some interviews with police to find out whether I was cooperative, and find out more about the regulations.”

The prosecutor couldn’t tell him how much the citation would cost, he said. “They said they could put me on probation, or write a restraining order or confiscate the drone permanently.”

BRIDGING THE GAP

Under Redondo Beach’s existing municipal code, flying a power modeled aircraft or glider heavier than 10 ounces is prohibited in city limits. These regulations were enacted 10 years ago, when flying gliders was a popular activity in the Redondo Harbor.

While a drone falls under the definition of a “power modeled aircraft,” the city attorney is reviewing whether the ordinance requires an update, said Lt. Joe Hoffman of the Redondo Beach Police Department. Until then, RBPD will keep a tab on drone usage in the city but refrain from citing users, he said.

“When drones are flying around at night, they light up and catch the eye,” he said. “It’s much like laws against text messaging – it could easily distract a driver. It may not actually be the fault of a drone operator. It’s more about public

El Segundo City Councilwoman Marie Fellhauer is leading the charge to place regulations to restrict drone use.

There’s too much potential for danger, she argues, if someone equipped with a drone harbored malicious intent. El Segundo is home to LAX, the Los Angeles Air Force Base, the Hyperion Sewage Plant and aerospace corporations.

Under FAA rules, a drone operator must acquire approval before flying within 5 miles of a major airport.

“Granted, I know there’s FAA (rules), but they don’t come out and enforce,” said Fellhauer, an LAPD sergeant by day. “Until that’s done, we need to bridge the gap for public safety. I know I’m looking at the glass half empty, but it can prevent a major catastrophic event.”