by Garth Meyer

As results came in after presstime for Wednesday’s Redondo Beach special election, it marked the close of a chapter in the saga of a handful of men aiming to bring legal cannabis stores to the South Bay.

The face of that effort became Elliot Lewis, CEO of the Long Beach-based Catalyst Cannabis Co. Lewis financed the initiatives to put retail marijuana measures on ballots this fall in Redondo, Hermosa and Manhattan Beach. Lewis also underwrote the push to recall Redondo City Councilman Zein Obagi, Jr.

He was not the first on the scene.

Before there was Elliot Lewis in the Beach Cities, it was Adam Spiker, a third-generation associate at Spiker Rendon consulting firm (based in Los Angeles and Orange County).

Spiker arrived in 2018 to speak to city councilmembers in the South Bay, including Torrance and Hawthorne, to gauge their interest in allowing cannabis stores. Spiker’s financial partner in the venture was a multi-state marijuana company publicly traded on the Canadian Securities Exchange.

Spiker said he found no interest from Torrance elected officials. Hawthorne city council members were open to marijuana stores, but wanted to write their own laws.

Redondo Beach council members were receptive too, as was Mayor Bill Brand. The city had already formed a cannabis steering committee working toward a retail ordinance.

Councilmen Nils Nehrenheim, and Todd Loewenstein later accepted campaign contributions in 2021 from the cannabis proponents, though Spiker said there was no “tit for tat.” Loewenstein donated his contribution to a nonprofit.

“The steering committee wasn’t doing anything,” Spiker said. “Not that I saw, but I might have missed something.”

In the third quarter of 2019, the Canadian stock markets crashed, and Spiker lost his financial partner.

“The next day they were pink-slipping and bailing water,” he said.

He had hoped that at least one or two of the Beach Cities would pass an ordinance or adopt an initiative to legalize retail cannabis.

“I thought we had a good chance,” Spiker said. “Put something credible out and have a dialogue.”

But he still would need significant financing.

In early 2020, Spiker brought in Tradecraft Farms, led by its CEO Barry Walker (also owner of the Cozy Nomad interior design shop in Redondo Beach), whom Spiker knew, as well as High Times, a cannabis store retail chain – the company that began by publishing its namesake magazine in 1974.

“We were desperate to move things forward,” Spiker said.

Walker referred Spiker to Elliot Lewis.

Lewis and his Catalyst Cannabis Co., became the third marijuana seller to join the effort, forming the Economic Development Reform Coalition of Southern California (EDRCSC). This is the name under which the South Bay initiatives were filed (alongside the required name of a resident proponent). Catalyst, TradeCraft and High Times agreed to be one-third partners. Spiker was kept on retainer as a consultant.

Who would be the frontman?

“We talked about it. I was supposed to be the spokesman because Elliot came off as brash sometimes,” Walker said.

High Times withdrew from the partnership after a year and a half.

“We loosely knew Catalyst, but not well,” said Paul Henderson, CEO of High Times, based in Venice Beach. He lives in Salt Lake City, a Brigham Young graduate and former Goldman Sachs associate. He was raised Mormon in San Diego.

“We had not won licenses,” said Henderson. “We bought licenses. The South Bay cities were of interest, so we did (the partnership) for a while, but it became pretty clear that the cities didn’t really want (retail) cannabis. It was a 3-2 vote. From informal polling of council members. It was going to be a real battle that we were not interested in fighting.”

High Times backed out in September 2021, just a couple weeks after the EDRCSC filed its first initiative in the South Bay: Redondo Beach.

“It was just a gut feeling. A lot of it was just the behavior of Catalyst,” Henderson said. “Things started to get heated. They were bullies at all costs. We don’t want to be associated with people who act like that. We had to walk away from over a $100,000 investment.”

High Times had no interest in filing initiatives and going to voters for approval. Their hope was through council adoption.

“(Catalyst) is very sharp. They’re kind of opposite of our approach — winning licenses by application,” Henderson said. “But we have a much larger business doing different things. They’re a little more gamblers, if you will.”

High Times does events, licenses its name, sells merchandise, and holds the annual “Cannabis Cup” national competition, which began in 1988 and for many years was known as the “Medicinal Cannabis Cup.”

“Cannabis is nothing more than a big business challenge,” Henderson said.

Now without a third of its financial piece, Lewis, Martin, Walker and Spiker continued on.

“It is expensive,” said Henderson. “But the reality is they’re calculating ROI. If they can win a license, each store could end up worth $10 million to Catalyst. I think anybody can make that trade.”

Lewis and Martin declined to be interviewed for this story.

While the EDRCSC worked to gather enough signatures to qualify its initiatives for ballots, the Redondo Beach cannabis steering committee sent a draft ordinance to the city council for review.

Steering committee member Jonatan Cvetko disputes Spiker’s characterization that the committee was inactive.

“That is absolutely wrong,” he said. “The committee had completed 95 percent of all the

recommendations for the council before COVID hit. The goal was to introduce the recommendations of the committee to the council by spring 2020.”

Under that schedule, he said an ordinance was expected to be passed in early summer 2020.

The city’s law ultimately would allow two stores in the city. EDRCSC’s initiative would include three, and ban delivery from companies based outside of town.

All the while, Cvetko, also the executive director of the United Cannabis Business Association,

spoke out adamantly against the EDRCSC proposal.

Lewis responded at every opportunity. His animated, profane persona was deemed “Patton-like” by an Easy Reader letter writer.

Cvetko has a delivery license in Montebello.

“There is a group that manages the license, however their focus is not on the Beach Cities,” Cvetko said. “And should Measure E pass they couldn’t apply if they wanted to because Measure E bans delivery of cannabis by companies not located within the city.”

Elliot Lewis graduated from Woodrow Wilson High School in Long Beach, and went to Cal Berkeley for a philosophy degree. He later taught English overseas, returned to Long Beach and got into real estate, while also working for a marijuana grower named Connected.

Lewis started in cannabis retail by applying for a Long Beach license.

“He had real estate in the right places in the city,” Henderson said.

With the license, Lewis opened a store under the Connected name. He subsequently applied for more licenses and went out on his own with Martin, converting the Connected stores to Catalyst Cannabis Co.

Spiker believes the Redondo Beach cannabis steering committee’s work or any other local city effort would not have led to stores in the South Bay.

“If not for the initiatives, none of these four cities would be moving forward with this,” he said.

The Catalyst/Tradecraft expenditures on signature gathering were a legitimate wager, he calculated.

“It was a risk proposition,” he said. “Kudos to Elliot for being willing to do that.”

But the recall effort against Council Member Obagi, Jr. was another matter.

“A lot of the industry is asking why,” Spiker said. “The recall turned the cities against (Lewis).”

Spiker, who was still working with Lewis when the idea for the recall came up, advised against it.

“I told him the recall gets him nothing,” Spiker said. “It doesn’t change the council. (Mayor) Brand still has veto power.”

A month and a half before this discussion, in November 2021, the consultant was present during a pivotal city council appearance by Martin on Zoom.

Spiker sat off camera with Lewis, Walker and a Catalyst employee named Natasha who operated Martin’s slide presentation. Martin was initially allotted 30 minutes. But Brand asked him to cut it to 15 minutes, because the council meeting was running late.

“Damian is an expert on policy, and also Catalyst history. He was the person to talk about this.” Spiker said.

Martin is also a former U.S. Naval intelligence analyst, who served in Iraq, Yemen, Britain and Chad.

As he sped through his presentation, the council questioned him about reports that his signature gatherers were lying to residents.

Martin responded, at one point, by saying he had the floor. He was told by the council he did not.

“I was motioning with my hands to (Martin),” Spiker recalled, “to drop his tone down a little. I felt horrible for him. I still do. It breaks my heart where things are at.”

Spiker parted ways with the partnership soon after Lewis announced the recall. He had been at work on the beach cities cannabis effort for four and a half years.

“People say, you brought Lewis here,” Spiker said. “I’ve been on an apology tour.”

The South Bay quest was now down to Walker, Lewis and Martin.

Martin, a Baltimore native, was a UCLA law student in 2015 when he began doing pro-bono work for the cannabis industry. He graduated the next year.

Lewis and Martin opened their first Catalyst Stores in 2018, and now have 14 stores.

“Elliot was a real estate guy. He hasn’t been in the game very long. He’s not considered one of these legacy operators,” Spiker said, referring to the cannabis generation from 1996, when California voters passed Proposition 215, the “Compassionate Use” law, legalizing medical marijuana.

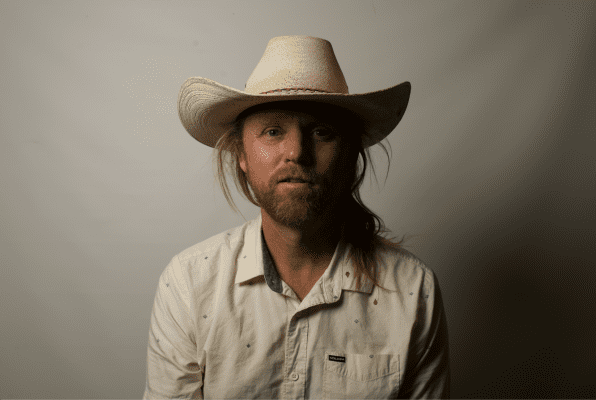

Walker is one such legacy operator.

His view of the effort to bring stores to the beach cities is one of tempered disappointment.

“Damian was the obvious choice to write the initiative measures. He is a mad scientist,” Walker said, noting Martin’s successful initiatives for other cities.

Walker had known and worked with Lewis before.

“We’re both traditional cannabis guys. We grow weed, we have for over a decade, protected by 215, when it was legal/not legal/legal/not legal/legal/not legal,” he said. “We were the guys who put our toes in the water.”

After Walker and Lewis agreed to work with Spiker in the attempt to open up the Beach Cities, Walker contacted High Times.

“It’s a name that is respected and quite frankly, could afford this expensive journey with us,” he said.

When High Times bowed out, the stakes rose.

“Creative differences; let’s leave it at that,” said Walker, of the reasons for High Times’ withdrawal. “It was a big financial blow to all of us.”

The EDRCSC hired signature-gatherers for four cities total – Redondo Beach, Hermosa Beach, Manhattan Beach and El Segundo.

Walker’s Tradecraft was founded 12 years ago, and now has three stores in California, five in Oklahoma, and one about to open in Maine.

“We have consistently made less money every year for the last 12 years,” Walker said. “The days of duffel bags full of cash are long gone.”

The question he hears most now is how could the EDRCSC spend as much money as it did on the Beach City initiatives. The signature-gathering contracts alone ran, on average, $110,000 each.

“Dude, we never expected to spend this much,” Walker said.

Like High Times’ Paul Henderson, and Spiker, Walker disapproved of the Obagi recall project, and did not contribute to what became a $300,000 campaign, including in-kind contribution of Catalyst budtenders knocking on doors to get signatures.

“I wouldn’t have put the energy to it,” Walker said.

If retail cannabis is approved in all three Beach Cities, Tradecraft, Catalyst and perhaps a dozen other companies may apply for licenses.

“Every man for himself, and I wish them the best, and I’m sure they wish me the best,” Walker said of Catalyst.

The Beach Cities could have up to eight licenses available: three each in Redondo and Manhattan, and two in Hermosa.

“I’ll bet, minimum, each city gets 10 good, solid applicants,” Spiker said. “Redondo probably more than 10 because there is more property available.”

Whatever happens, it appears Walker’s risk in the South Bay is less than Lewis’ and Martin’s.

“If you’re breaking even in this business, you’re doing great,” Walker said. “I’m vertically integrated. We’re a seed-to-sale company.”

Tradecraft is owned by Dub Brothers Management – Walker and his brother. They started on the margins of the industry, well before 2016’s Proposition 64.

“We’re skid row farmers,” he said. “You can tell how long someone has been in the cannabis business by how sh—y the neighborhood is for their (grow operation).”

Tradecraft rents five former sewing factories in downtown Los Angeles.

“The sewing houses had enough power,” Walker said.

“This is a generational opportunity. Years ago there was a lot of money to be made. There still is. But this is a long game. We’re the pioneers in an industry that is going to be here forever.”

After California’s legalization, national investors appeared with money but had no knowledge of cannabis and its culture – for example, what strains are for balms, edibles, medicinal and recreational uses.

Walker and Tradecraft knew these things.

Now, with an infusion of East Coast money, post-legalization, Tradecraft has 80, one thousand-square foot “hoophouses” (small greenhouses) in Lancaster, at the former site of one of the world’s largest onion distributors.

“We started two and a half years ago, when the bottom hadn’t fallen out yet,” Walker said of the EDRCSC in the South Bay. “We started it and we’re going to do it. It’s almost over, the final push.” ER