Dianne Wiest is splendid in Samuel Beckett’s “Happy Days”

Where are we? On a scraggly, sandy, near-barren hill, with a corseted woman buried up to her waist. She’s dressed entirely in black. It’s a very bright day, the sky as blue as can be, the sun unrelenting.

Samuel Beckett wrote his absurdist, existentialist “Happy Days” in 1961, and it premiered at the Royal Court Theatre in London in 1962. It’s now at the Taper and starring Dianne Wiest (an Academy Award-winner who starred in Woody Allen’s “Hannah and Her Sisters” and “Bullets Over Broadway”). The production, directed by James Bundy, is simple and austere, and yet open to many interpretations.

It’s a two-person play, Wiest as the middle-aged Winnie and Michael Rudko as her preoccupied husband, Willie, but for all intents and purposes it’s one incredible monologue.

Within reach Winnie has a satchel and an umbrella, and from the first of these she pulls out toiletries, a mirror, a magnifying glass, and even a pistol. She reads labels from bottles (“Fully guaranteed, genuinely pure,” etc.), and chatters away: “It’s going to be a happy day.”

Both characters have limited mobility and see the world from their confined perspectives, perhaps like the chained figures watching shadows in Plato’s cave. Willie, it seems, resides in a burrow. Does that mean he has tunnel vision?

Winnie puts a positive spin on things, but it’s impossible not to cringe because, as the landscape implies, her life is not only barren, she’s trapped in it… a bourgeois existence? A loveless marriage? Dashed hopes and dreams that she’s done her best to forget? And why has that pistol come out of her satchel?

Periodically there’s the loud clanging of a bell, a wakeup call, signifying that a new day is dawning or perhaps ending. If we see it as a sort of infernal alarm clock, does that mean that life is a crazy, claustrophobic dream, with no exit (except death), as we might find in Sartre or Buñuel?

When the audience returns for the second act everything’s the same, except that Winnie is buried in sand up to her neck. Now she can’t even use her hands. Yet she still tries to project a positive attitude, although the cracks do show. The pistol is still there (and we all know Chekhov’s statement that if a gun is produced in the first act it needs to be fired in the second), but she has no way of reaching it even if she desired.

We may not have been able to make logical sense of much of Winnie’s monologue (I think James Joyce is in the background), but that gradual sinking into metaphorical quicksand can be haunting and deeply unsettling.

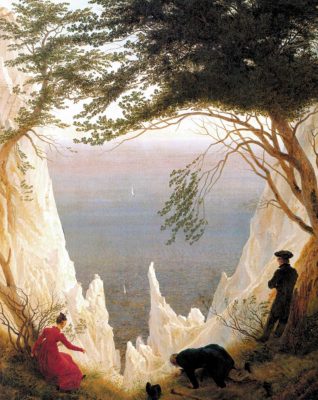

When Beckett traveled to Germany in 1936 he visited museums and discovered the work of Caspar David Friedrich, whose “Two Men Contemplating the Moon” is said to have had some bearing on “Waiting for Godot.” On his hands and knees, with his top hat at his side, Willie recalls a similarly clad figure in Friedrich’s “Chalk Cliffs on Rügen,” a painting perhaps as enigmatic as Beckett’s play. Possibly Bundy, the play’s director, would have some insight into this, I don’t know.

This is the Yale Repertory Theatre production of “Happy Days,” the scenic design by Izmir Ickbal, costume design by Alexae Visel, lighting design by Stephen Strawbridge, and sound design by Kate Marvin, all these ingredients working seamlessly together.

The result is an alluring but demanding work which, nonetheless, not everyone in the audience may have the patience to endure. You may not understand it, you may not even like it, but I think you will be moved more than you realize, because this portrait of a confined and isolated woman goes far, far below the surface and touches on the essential concerns of our own existence, no matter who we are.

Happy Days, by Samuel Beckett, is onstage through June 30 at the Mark Taper Forum, 135 N. Grand Ave., downtown Los Angeles in the Music Center. Performances, Tuesday through Friday at 8 p.m., Saturday at 2:30 and 8 p.m., and Sunday at 1 and 6:30 p.m. Exceptions, no 1 p.m. performances on Sunday, June 2 and 23; no 8 p.m. performance on Saturday. June 8; and no 2:30 p.m. performance on Saturday, June 15. Closes with the 1 p.m. performance on Sunday, June 30. Tickets, $115 to $32. Call (213) 628-2772 or go to CenterTheatreGroup.org. ER