Roger Bacon: Hermosa Beach’s ‘Wheels and Deals’ man

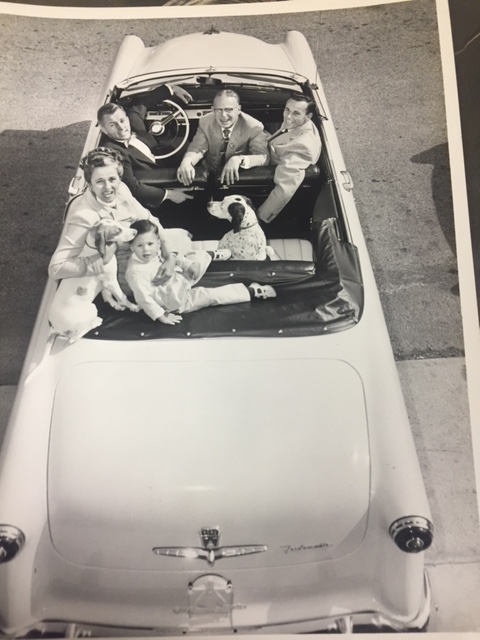

Roger Bacon behind the wheel of a 1954 with dad Les, brother Bob, and mom Marion. PHoto courtesy of the Bacon Family

by David Hunt

[Reprinted from Easy Reader, July 3, 1997. Bacon passed away on March 1, 2019 at age 88.]

It’s easy to picture Roger Bacon in the middle of a three-ring circus, attired in red top hat and tails and shiny black leather boots, snapping his whip at snarling lions, climbing atop a lumbering elephant, serving up death-defying acts of courage and the occasional shot of seltzer to the face. Bacon, a stocky, barrel-chested man with a ruddy complexion and sandy hair, never ran away with the circus. But for 14 years, between 1951 and 1965, he walked the line between showman and salesman to sell cars in Hermosa Beach.

His energy and antics helped propel the family business, Les Bacon & Sons, to its place as the top-selling Ford dealership west of the Mississippi. Along the way he beat labor union attempts to organize his salesmen, set a whale carcass on fire in front of the dealership as a publicity stunt, dug holes in local streets to test suspension systems, sponsored beauty contest to attract crowds, and led parades of new cars through the beach cities. “We drove through the town like we owned it,” he said.

In 1954, Bacon arranged to have a Ford sedan perched on top of a 60-foot-high pole at the Pacific Coast Highway dealership, then climbed the pole and sat on the car’s front hood to prove his claim that he was “America’s highest car trader.”

When local television offered the chance to reach a mass audience through live programming in the late 1950s, Bacon took to the airwaves to sponsor car races, football games and variety shows. His live commercials, more often than not, ended with a frantic Bacon shouting to the director, “Don’t cut me off, I’ve got more to say.”

Bacon’s stunts were memorable. He trained a chimpanzee to steer a car while chewing on a cigar. And he brought alligators, horses, gila monsters, spiders and snakes on the lot to thrill kids and fascinate their parents. “It was a circus here,” he said.

But it wasn’t all fun and games. Bacon and his older brother were hard-driving, competitive men. Their fights were legendary, especially after their father died in 1959. Today three decades after the close of Les Bacon & Sons, they rarely speak to each other.

Bacon now runs the Ralphs Shopping Center at the site of the old family dealership. But he’s like a ringmaster without a circus. His confident swagger and booming voice don’t seem so charming without a television crew in attendance. And, he frankly admits, “I piss off a lot of people.”

Bacon’s stage is Hermosa Beach. He battles city planners, impatiently instructs wayward councilman and patrols his shopping center like a star awaiting his close-up. Instead of variety shows, Bacon now hosts a public access TV talk show twice a month. He angered some residents two years ago during a city-sponsored Christmas parade, when he insisted that the event coincide with the opening of a Starbucks franchise at his shopping center. Santa Claus was forced to ride behind Bacon who led the parade on a rented elephant.

Roger Bacon, founder of the Hermosa Beach Surer Walk of Fame, in 2007 with inductee Mary Setterholm. Photo

An early entrepreneur

Bacon grew up in Manhattan Beach in the 1930s and 1940s. He started his first business venture at 6, catching and selling halibut at the Redondo Beach pier. But the real money, he learned a few years later, was in bait. The only problem was competition.

“I was catching sand crabs and selling them and the guys who had the concession to sell sand crabs were Oscar’s Bait and Tackle and Red’s Tackle shop. So I would sneak out there and start selling fresh sand crabs and undercut them on price,” Bacon recalls. “If they were selling them for 25 cents a dozen I’d sell them for 20 cents a dozen.”

roger Bacon with a 126 pound Marlin caught from aboard his boat “Get off Your Couch” in 1976

More than once Bacon was chased off the pier by angry employees of the bait shops.

By the time he was 11 Bacon had a thriving house cleaning business, employing several neighborhood kids. The work was ard and Bacon was an exacting boss. “If they didn’t do a good job, I wouldn’t keep them.”

World War II had created a labor shortage and Bacon was happy to fill the void. As a result, he accumulated a hefty nest egg — more than $500, he says. Bacon cut the center pages out of a book and hid the money inside, confident that it was safer there than in a local bank.

“My mother decided I had too many trashy books and gave them away to the Salvation Army,” Bacon says. “I had to run down there and go through a hundred books. I almost had a heart attack.”

Luckily, Bacon recovered the money and remained on a sound financial footing. In fact, he says, he was the most solvent person in his family during the war.

“It got to the point several times when I got to be in my teens when my mother would borrow money from me because she ran a little short,” Bacon says. “And I couldn’t charge her interest, because she wouldn’t let me.”

Bacon’s older brother, Bob, wasn’t so lucky. “By the time I was 13 or 14 my brother used to want to take a date out but he didn’t have any money-he was busted. So I’d loan him money and I took his fishing pole, his swim fins, and his face plate as collateral.”

After the war, Bacon’s father, who managed a Hudson dealership in Los Angeles, decided to buy a business closer to home. In 1949 Les Bacon opened a Studebaker showroom on Pacific Coast Highway in Hermosa Beach. Bacon, then a student at Redondo Union High School, worked in the parts department.

In 1951 Bacon used his savings to open his own imported car dealership at 7th Street and PCH in Hermosa. Roger Bacon’s Imported Cars sold MGs and Morris Minors, then expanded to include a number of other makes, including the Hillman Minx, Sunbeam Talbot, Rover, Humber, Austin Healey and Allard lines.

In 1954, with British car sales dropping off, Bacon decided to open a Volkswagen/Porsche dealership in Hermosa, but had trouble getting approval to sell the cars. To impress officials at the Porsche plant in Germany, Bacon brought a Porsche from a dealer in Hollywood and took a photo of the car next to a Black Widow test jet at Northrop Corporation. He mailed the photo to Dr. Porsche, the company’s founder, “because there was a direct correlation between the Porsche and the jet as far as aerodynamics was concerned.”

Bacon also made friends with John and Eleanor Von Neuman, the owners of the Hollywood dealership, and convinced them he could sell the little imports at the beach. His persistence and creativity paid off and Bacon picked up the Volkswagen/Porsche lines that year.

“I really started making money,” he says. In fact, Bacon was doing better with imports than his father and brother were doing with the Studebaker dealership.

Les Bacon needed Roger Bacon and he needed a more successful make of car to sell. In 1954 he got both. “My dad negotiated to buy the Ford dealership in Hermosa Beach. And he came down to me and said, ‘I want you to come up to the new Ford store.’ I said, ‘I don’t want to. I’m very happy down here.’ Well, my father was very persuasive and his credit was on with the bank to give me the opportunity to have those cars there.”

Without his father’s credit backing, Bacon could not have remained in the imported car business. And so a deal was struck.

“The agreement there with my father was that I would work one shift and my brother would work another shift and there would be some daylight between our shifts because we didn’t get along too well,” he says.

While Beacon was honeymooning in Hawaii with his first wife, Gwen, his father sold the imported car dealership. The buyer, Te Corozzo, later sold the dealership to Vasek Plak, who built an imported car empire in the beach cities before his death earlier this year.

Bacon inherited his showmanship from his father, he says. “My dad was a P.T. Barnum man,” he laughs. “When I was a kid I’d go to his dealership in L.A. and he had a coral built and put horses in it. ‘Trade in your old nags here,’ he would advertise.”

When he worked at Boyd H. Gibbons’ dealership in downtown Los Angeles, Les Bacon bought life-like mannequins of all the famous stars of the 1920s and 1930s-Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, Will Rogers and Wallace Beery. He put them in a bus with the name of the dealership emblazoned on the sides and drove them all over the city. “All the movie stars go to Boyd H. Gibbons,” a sign proclaimed.

When the Bacons opened the dealership in Hermosa Beach, they tried similar stunts to attract buyers and browsers. Salesmen dressed as sailors one day, cowboys the next. Another day they marched in front of the showroom, carrying picket signs demanding the right to buy a Ford. But it was television that revolutionized car sales-thanks in part to Roger Bacon’s inflated sense of the dramatic.

“Our newspaper advertising didn’t seem to be pulling as well as it used to so I had an opportunity in 1957 to buy in to a live television show in Redondo Beach at the old Red Barn nightclub, next to the old salt water swimming pool,” Bacon says. “It was a special show with a beauty contest and weightlifting competition.”

The emcee of the show was Bill Welch, a local celebrity who hosted several programs on KTTV. He generously offered to help Bacon with his commercial. But then the camera switched to Bacon, he grabbed the microphone from the startled Welch and launched into an enthusiastic pitch for a 1957 Ford Fairlane.

At the end of his 1-minute time limit, Bacon showed no signs of ending his commercial. A crew member slashed his hand across his neck, the traditional cut sign, but Bacon ignored the sign and continued with his pitch.

“Don’t cut me off,” he implored the director on live TV, “I’ve got more to say.”

The director, who had never had a sponsor attempt to take over the show, hesitated, then finally pulled the plug. Bacon put on the same melodramatic show at each commercial break, to the delight of the television audience.

“I came back to the lot and my dad ran up to me and gave me this great big wet kiss on the side of my cheek like he used to do. We had sold 17 cars off those pitches.” Bacon says. “I stole the show. I think I bought the whole show for either $500 or $1,000. And my dad said, ‘Go buy more television time, let’s go on the air.’”

Bacon went to local station KTLA and agreed to sponsor the Sunday afternoon movie from 1 to 2:30 p.m., followed by Jalopy Derby from 2:30 to 5 p.m. Bacon’s only condition was that the station use the popular roller derby announcer, Dick Lane, to announce Jalopy Derby.

Lane came down to Hermosa Beach to meet Les Bacon and drove away in a brand new Thunderbird. He agreed to host the show.

Lane and Bacon had a simple formula to boost the show’s dismal ratings. “We wanted to get more life in the races and we said to the drivers, ‘If you guys get mad at each other every once in a while and if you really want to have it out, it’s okay with us-we’re going to show it on camera.”

The drivers got the message and began staging fist fights every four or five laps into the wall, then the guy would get the car off the wall and go after the other guy and yank the other guy out of the car and there’d be a fist fight in the dirt.” Bacon says. “And we’d put the camera right on them.”

The rating shot up, from half a percent to 6 percent or better some weeks.

Bacon used a similar tactic when he sponsored a semi-pro football team, the Anaheim Rhinos, in 1960. The rough and tumble team got into so many fights on the field, the players would routinely be ejected by referees. During one game, the Rhinos didn’t have enough eligible players to finish the game. Bacon put new jerseys on some of the players who had been ejected, and sent them back onto the field.

As a publicity stunt, Bacon began taunting the Los Angeles Rams, comparing them unfavorably to his Rhinos.

“I’d get on the air and say, ‘Our Rhinos are so good, they could beat those Rams. Those Rams are nothing this year. Do those Rams have enough guts to scrimmage us?’ So it’s in the newspaper all the time that the Rhinos are challenging the Rams. It was so humiliating for them. Every time the Rams lost a game I’d say, ‘Well, the Rams lost another one and our Rhinos won.’ Oh God, the controversy. We sold cars off that.”

The Rams finally accepted the challenge and beat the Rhinos, just to stop the taunts from Bacon.

Bacon began pre-empting his Sunday movie for a live variety show, staged at the Hermosa Beach dealership. The show featured such talent as Roberta Lynn, the original Champagne girl with the Lawrence Welk Band, singer Billy Daniels and TV star Duane Hickman from the Dobie Gillis show. Bacon, in his element, hosted the show.

During commercial breaks, Bacon used silly animal tricks and elaborate stunts to draw his audience down to the dealership. He hired a pilot from the nearby Torrance airport to fake an airplane crash one week, going so far as to shake the TV camera, then cut to black momentarily to suggest that the plane had dived right onto the lot. When the program returned to the air, Bacon had the camera operator pan up to the roof of the dealership, where he had placed the wreck of a small plane. On Bacon’s cue, a man climbed out of the wreckage and asked where he could buy a Ford Barcon for just $1,750.

Bacon, dressed in full western attire, would ride a specially trained trick horse named Denver around the lot during another commercial break.

“I’d say to Denver, ‘What do you think of this Chevy Impala that we took in on trade?’ and Denver on command would shake his head no. So then I would turn the horse around and I’d back him up to it and I’d say, ‘Denver, I want you to rethink about this car. You know, we’re not a Chevy dealer. They build these cars and they’re our competitor. But I’ve got to sell this car and I’ve got more Chevys to sell. So come on, Denver, what do you really think of this Chevy now you’ve looked it all over?’ And the horse on command would kick the car and put a big dent in the door of the car. So I’d get off the horse and say. ‘Well, I guess they’re not making them as good as they used to. We’ll knock another $1,000 off of this car.’”

Enraged by the ads, General Motors ordered Bacon to stop the stunt. Bacon, sensing valuable publicity in a lawsuit, refused. GM backed down.

Bacon was equally bold in taking on labor unions in 1959, when the retail clerks tried to organize the dealership’s salesmen. The battle took over a year and cost Bacon & Sons thousands for dollars. It was a titanic battle.

Union members formed a huge picket line at Bacon’s dealership, halting the delivery of new cars to the lot and preventing television crews from working on Bacon’s variety shows and commercials.

Bacon met with the head of the TV engineers’ union, bought him lunch and convinced him to let Bacon televise his commercials from the backyard of his father’s house, which was located just east of the dealership.

The TV cameras were set up so they could shoot over the back fence of the home and pan the cars sitting on the lot. Bacon was making incredible deals.

“I put a car on at one o’clock for $5, at two o’clock for $10, at three o’clock for $15, at four for $20 and at five for $25. We had a thousand people come right across the picket line, knocking the picket signs down. The didn’t care.”

After a few months the TV engineers agreed to resume shooting on the lot and the effort to organize the salesmen was broken.

With the death of his father in 1959, Bacon lost his enthusiasm for the family business. “All the fun was gone,” he says. By 1965 the dealership had been sold. The new owner never made a profit and the lot closed the next year. The property lay vacant for 10 years.

By 1969 Bacon was broke. Personal failures-two divorces and the estrangement from his brother-were now compounded by financial difficulties.

He couldn’t get a job at any dealership in the area. “No one would have me. They thought I would try to take over,” he says. But he could still buy and sell cars.

For the next few years Bacon went from dealer to dealer, buying and selling, wheeling and dealing, and stashing away the modest profits. Slowly, he stabilized his finances.

In the mid-1970s Bacon took a long forgotten lot he owned in South Redondo and built a 28-unit apartment complex. With the profits from the sale of the apartment building Bacon purchased the vacant property where Les Bacon & Sons once stood in Hermosa Beach. In 1976 he built the Ralphs Shopping Center.

Today, from his office overlooking the shopping center, Bacon says he is “basically happy.” He takes pride in his two children, Robin, a school teacher, and Stephen, who works in the contracts department at the William Morris Agency. And he’s tired of fighting, he adds. Although he nearly came to blows with a guy while waiting in line to buy groceries at Trader Joe’s recently.

Bacon blames a severe case of tinnitus, ringing in his ears, with contributing to his edginess for years. The condition is gone now, to his relief.

Bacon, like the grand Vedder Windmill in Greenwood Park at the edge of the shopping center, is a fixture in Hermosa Beach. While no one is lobbying to preserve Roger Bacon, the irascible Bacon is fighting hard to save the windmill, a monument to another, simpler time in Hermosa Beach.

Like the windmill, Bacon no longer seems dedicated to his highest and best use. Being a landlord or a shopping center developer, despite the financial rewards, can never equal the egocentric thrill of grabbing a microphone on live TV and offering the deal of a lifetime.

“Get off your couch and come down to Hermosa Beach. I’m going to sell you a Ford.” Bacon used to bark, pointing directly at the camera and into the living rooms of suburban homes. And they came all right, by the thousands, to see the man on the horse, or the airplane, or the alligator.

“It was fun and it was exciting,” Bacon said. “TV really put Hermosa Beach on the map. I miss that more than anything else in the world.”