The South Bay brewing industry was launched somewhat inauspiciously in 2009 with two men, a minivan, and a frothy dream.

Rich Marcello and Joel Elliott were surfers, best friends, and decidedly non-corporate; they wanted to do something they believed in, and something that connected people.

They believed in good beer and in their native stomping grounds, the South Bay. They rented a 1,000 sq. ft. warehouse in Torrance and bought a small fermenter. They called themselves Strand Brewing Company and set themselves a simple mission – to sell beer everywhere the physical Strand reached, from the South Bay to Malibu. Their business plan was likewise elemental.

“We will not be outworked,” Marcello said. “That’s not a motto. It’s a necessity.”

Elliott, an autodidact, taught himself how to brew, designed a label featuring the iconic image of a local lifegaurd tower, and started working 20 hour days to concoct the brewery’s flagship 24th Street Pale Ale. Marcello made himself at home in a Chrysler Town & Country minivan, where he’d spend the next years logging a few hundred thousand miles and acquainting himself with every beer-inclined person from here to Malibu. A month after launching, they produced their first batch of beer, borrowed three kegs, and took them to Naja’s, the South Bay’s original beer mecca on the Redondo Beach International Boardwalk. The kegs sold out in ten hours and Strand was off and running; they sold 400 barrels of beer in 2010, their first full year in business.

Last year, Strand expanded into a 36,000 sq. ft. warehouse and tap room. This year, they will sell 7,000 barrels of beer (about 220,000 gallons).

“We are right on track to do what we said we were going to do seven years ago,” Marcello said. “I am most proud, at the end of the day, that Joel and I own it — just the two of us, 50-50. That’s hard to do when you grow. We have retained 100 percent control of every decision for our brewery.”

Strand’s story is both foundational to and emblematic of the South Bay brewing industry. Seven breweries have launched locally since Strand, making the area a destination for craft beer lovers. As the LA Times reported, “The South Bay is a hotbed of craft breweries, brewpubs and beer-focused bars.”

The area’s second brewery, El Segundo Brewing Company, was launched by aerospace engineer-turned-brewer Rob Croxall and cicerone Tom Kelley in 2011. ESBC brewed 300 barrels its first year and last year expanded its brewery tap room on El Segundo’s Main Street. The company is on target to sell 6,000 barrels this year.

Theologian-turned-brewer Henry Nguyen and his wife Adriana launched Monkish Brewing Company in Torrance in 2012, the same year husband and wife team Jonathan and Laurie Porter moved their fledgling Smog City Brewing Company from Tustin to Torrance. In 2013, two more breweries joined the local ranks: King Harbor Brewing Company and Dude’s Brewing Company. In 2014, Absolution Brewing Company launched (and did so in a big way, selling 2,000 barrels in its first year, on target for 12,000 barrels this year). And this year, HopSaint Brewing Company, the brainchild of legendary South Bay restauraunteur Steve Roberts and master brewer Brian Brewer, has launched as a brew pub and will soon begin distributing its beer.

But the growth of the local brewery scene is about something more than the number of barrels of beers emanating annually from the South Bay. The brewing of local beer has has helped give rise to a vibrant craft-centric subculture that goes beyond the breweries themselves — the tap rooms of each brewery are places of emphatically local art, music, and food. They are community hubs.

“The positive thing is I think you have most breweries putting out really quality products, and that is a really good statement for what is going on in the South Bay,” said Croxall, ESBC’s brewer. “I think a lot of us are viewed as a focal point of the community. I know El Segundo [Brewing Company] certainly is, and I think some other breweries’ place in the community are also as a gathering point. That is a point of pride for all of us — that wasn’t here ten years ago. And we don’t take that for granted. We are very appreciative of how the community has embraced us.”

This Saturday, the local breweries will themselves gather for the Third (Occasionally) Annual Froth Awards and Beer Experience at Saint Rocke in Hermosa Beach. The event, first organized in 2013, will be a celebration of both local beer and the sense of community the breweries have helped foster. Five local bands will play, a South Bay trivia contest will be held, and food will be paired with local brews. This year’s event also marks the reemergence of Steve Roberts, who as the founder of Cafe Boogaloo back in 1995 was among the first local operators to bring craft beer to the South Bay. Roberts will do three special food pairings, including one featuring a beer from Hopsaint brewmaster Brian Brewer.

Marcello, who was a regular at Boogalo back in the day, said Roberts provided an example that remains relevant in every good brewery that has emerged in the South Bay.

“He was pre-everything,” Marcello said. “He told Budweiser to take a hike from Boogaloo — he was so far ahead of the pack, people didn’t know what he was doing. And he stuck to it, kept his ground, and never wavered from that, which is just an admirable trait. You know, they dangle carrots, and he took heat, but he said, ‘No thank you.’”

Breweries, Marcello said, likewise have to remain constant.

“I realize I can’t be everything to everybody, or I am going to be nothing to myself,” Marcello said. “When I shave, and I look in the mirror, I look at myself and I’m pretty happy with the decisions I’ve made, for good or ill. It’s not for perfection.”

Holy beer

Café Boogaloo was like some kind of strange bluesy unicorn when it opened in 1995. Nothing like it existed: a blues bar that featured “farm-to-table” cuisine (Roberts is a regular at the Santa Monica Farmers Market, sourcing nearly all his produce from farmers he’s now known for decades) and had 27 handles of all craft beer before the term “craft beer” even existed.

It was, in fact, a “beer-to-table” restaurant — many of the breweries who are now legendary in the craft world, such as Port Brewing or Anderson Valley, didn’t even have distribution yet. So Roberts often drove to breweries himself in order to obtain the beer.

“I’d go surf Trestles, the drop by Pizza Port Brewing and pick up a few kegs of beer,” Roberts remembered.

His was the first local venue to feature what has become perhaps the most revered craft beer in the world, Pliny the Younger, from Russian River Brewing Company.

“I remember when IPAs came on the market and I couldn’t give it away,” Roberts said. “I swear to god. I had three on at the same time — Racer 5, Anderson Valley, and Pliny — and no one would drink them.”

The idea any bar wouldn’t carry mainstream beers wasn’t just novel, but borderline insane.

But it was because of pioneers such as Roberts — and before him Father’s Office in Culver City, and Naja’s in Redondo — that a market for craft beer took hold.

“I think people are more in tune with what they ingest, because all the Food Channel stuff and just a growing awareness,” he said. “Wouldn’t you rather have something made by those hard-working, local guys down the street, instead of something made by some big corporation.”

HopSaint takes those ideas and brings them to a new level. Their goal is to take beer near to a point of near-holiness. HopSaint’s website offers a definition of hops as a “liquid saint” that wards off spoilage, pleases the palate, and puts “the bitter in the beer” and describes the brewery itself as “a community built on craft beer.”

And in brewer Brian Brewer, who previously worked for Stone Brewing and then ran the Brewery at Abigaile in Hermosa Beach, Roberts has found a brother in brew. HopSaint’s beer menu delves deep into its ingredients, and features seven brews, including a “Bubble Butt Blonde” with 2-row, Pilsner, and Maris Otter malts and both Liberty and Czech Saaz hops, a “Born of Rebels” double IPA that uses five different hops as well as an “Experimental Stout Batch #1” that uses two different kinds of oats and two malts.

“He’s really meticulous about everything,” Roberts said of Brewer. “Everything is clean, clean, clean. He’s detail oriented and has nothing but the best ingredients to deal with…His beers are pristine. We’ve only started, and he’s come out swinging.”

Beer and love

Meticulousness is a deep value shared among great brewers. El Segundo Brewing’s Rob Croxall was an aerospace engineer before leaving that career to launch a brewery in his beloved hometown. His concern with controlling exactly how his beer is presented has meant ESBC has not sought to expand far beyond the local market, other than self-distributing to Orange County and San Diego — Croxall simply does not trust someone else to ensure that his beer arrives as fresh as possible to its drinker and refuses to compromise its quality. His beers, particularly a series of IPAs, DIPAs, and TIPAs as well as the ridiculously pleasing Citra Pale Ale, are known for their beautifully crisp edge, something Croxall says “is no accident” due to his emphasis on making sure no ESBC beer older than 90 days is ever consumed. ESBC stamps the brew date on the very front of every bottle.

“Being able to control dates on the shelf in everything we do is based on freshness and is a very big deal to us,” Croxall said.

The brewery’s recent collobaration with pro wrestler Steve Austin, the “Broken Skull IPA”, has garnered national attention from the likes of Rolling Stone and USA Today and has opened doors to some wider distribution — but even in this instance, Croxall is very particular to know each distributor “knows our game.”

If the beer won’t come to somebody far away, it turns out, people far away will come to El Segundo. Croxall said 66 percent of credit card swipes at the the brewery’s tap room are new customers. “That’s people coming from out of town to see us — we bring people to the area, day after day,” he said. “It’s amazing. We show folks from the city this data and it blows their mind.”

It’s about a love affair for all things local, and in Croxall’s case, this means the five square miles of his beloved El Segundo. His beers, and the inventive label art by El Segundo’s Boiling Point Creative Group, almost always give homage to his hometown — Mayberry IPA, for example, is named for El Segundo’s small town feel, Hyperion Stout is named for the nearby waste treatment plant, and Hammerland DIPA is named for the local surf break.

“I really want to keep everything grounded and tied to El Segundo as best I can,” Croxall said. “That’s what it’s all about.”

A similar ethos runs through most other local breweries’ way of doing business.

King Harbor Brewing Company’s intention in launching was to embody the South Bay lifestyle in a beer. Co-founders Tom Dunbabin and Will Daimes met because their girlfriends (now wives) played beach volleyball together and the couple would go out for dinner and beers afterwards. One beery night, the idea of launching their own brewery arose, and for the next three months they met at Java Man coffeehouse in Hermosa Beach nearly daily to develop a business plan.

Dunbabin, who, like Croxall, was an aerospace engineer, saw an opening in the market for beers that weren’t as high in alcohol content.

“Our goal was all about bringing the South Bay lifestyle into a beer,” Dunbabin said. “We grew up surfing, playing volleyball, going to the Fun Factory and causing trouble…Our end goal was having a business that supported our families and having our friends work at it and to become a part of the craft brew community. It was all about what we loved. We didn’t have our sights set on getting in a bunch of debt to make a big company we could sell to a bigger company.”

They recruited a young brewer named Phil McDaniel, who’d worked for the highly respected Bootleggers and Stone Brewing companies, and identified something they felt was missing in the local market: relatively low-alchohol beer that would fit the active South Bay lifestyle.

“We thought, ‘How can we make kickass beer, but one that doesn’t have to have to be super high in ABV [alchohol by volume]?” Dunbabin said. “We wanted 4.5 to 6 percent rating, so you could enjoy dinner and have four or five pints and still get home on a beach cruiser…I mean, it’s cool, but if I drink a 9 percent stout, I’m toast….We wanted a beer you could put in a coffee cup and ride your bike to the pier, something that fits that South Bay lifestyle.”

KHBC’s beers have met that mark. The popular Abel Brown is an American brown ale the brewery describes as a breakfast “dark beer brewed for the beach” while a series of session beers have been among the first of their kind on the local market. But the brewery has also been inventive, particularly with its Quest Pale Ale, which keeps the same grains but rotates different hops throughout the year — including Rakau, Citra, Mosaic, El Dorado, and Huell Melon hops — and through the contrast bring each hop profile into sharp relief.

And in keeping with its social ethos, KHBC has excelled in creating gatherings — its brewery tap room and a second waterfront tap room on Redondo’s International Boardwalk have hosted art shows, local music, and food trucks.

“Our outlook on beer is beer isn’t the end goal,” Dunbabin said. “As much as we want people to seek out our beer and get stoked, it isn’t about sitting alone and and really focusing only on that beer. Our beer is part of a greater experience that we want people to have in our tap rooms, enjoying music and friends and the sunset and maybe learning about brewing. Beer is only part of what we are doing.”

Beer and business

The Dudes Brewing Company takes a less than haughty tone in its approach to the brewing business.

Founder Toby Humes and vice president of sales Scott Shaw both left the corporate world to build Dudes.

“The Dudes, Toby and myself and a group of guys and girls, we like beer,” said Shaw. “We have likeminded attitudes. The day may be stressful, and we take the process of brewing beer seriously, but everything else is just going to kind of happen…We just want to make awesome beer and have a good time.”

The Dudes started big. They were ahead of most the craft industry in that they came out of the gates canning their beer, rather than bottling, something that would soon become more common. They had a large brewing capacity, were distributed by MillerCoors, and produced 4,000 barrels in only their second year.

But then they realized, Shaw said, “That is not The Dudes.” They wanted better control over their product — knowing, for instance, that it would be kept cold from the brewery all the way to the consumer — and so found a more regional distributor, Southern Wine and Spirits. In the last year, they recruited brewer Alex Rabe.

Their signature beers, the Double Trunk DIPA and Grandma’s Pecan English Style Brown, are big and bold. Rabe, a product of the vaunted UC Davis master brewers program, was brought in to both up quality and produce some new innovative beers.

“With so many breweries coming, you have to up your game or be left behind,” Shaw said.

Rabe came out of the gates with a very well received session IPA called Bohemian Hopsody, a blending of Mosaic, Simcoe and Citra hops. The beer is the “offical beer of 95.5 KLOS”, the radio station on which Shaw appears regularly to talk beer with hosts Heidi and Mike.

This year promises to be a big one for The Dudes, who hope to produce 10,000 barrels and carefully branch out beyond regional markets, into Arizona, Nevada and even the Midwest. Their uniquely Southern California DNA is part of the draw elsewhere, but The Dudes highest priority is to become a core brand locally.

Shaw, who formerly worked for Budweiser and Pernod Ricard, said consumers are reaching a turning point.

“I left the big beer and big spirit world because I saw the writing on the wall as to where craft beer was going,” Shaw said. “Locally, it used to be all the guys going down the beach for the AVP tour would grab Budlight and Michelob Ultra. They are still doing that, but not as much — they are grabbing Dudes cans and hitting the beach.”

The newest arrival to the South Bay, Absolution Brewing Company, comes from a different direction. South.

Founder Steve Farguson has been involved in the craft brewing scene since before it existed locally. He was involved, on the finance side, in the original epicenter of American craft brewing, San Diego County — home to Stone, Coronado, Ballast Point, Karl Straus, Pizza Port, North Flash, and several other brewing companies.

Farguson remembers coming north for an LA Beer Guild festival at Sony Studios seven or so years ago. He was aghast when he found Corona and Heineken on tap.

“I’m like, ‘Oh my goodness, this is the wasteland,’” Farguson said.

But Farguson also saw an opportunity. San Diego was saturated with breweries, but LA was so much larger, it seemed inevitable that it would become a brewing epicenter. And then he saw all the brewing activity arise in the South Bay and decided to join the fray. In Torrance, not only would Absolution join four other breweries within walking distance — Farguson notes that breweries are the second largest driver of tourism in San Diego, due to their proximity — but the location also gave him good access to serve the Orange County and larger LA markets.

“So Torrance, in my opinion, was a sweet spot,” Farguson said.

He likewise analyzed the beer Absolution would make through the prism of his business plan. He’d been involved in the craft beer industry since 1991, and from the outset the idea was to challenge the status quo. In the age of corporate brewing — an outcome of U.S. Prohibition in the 1920 — few styles of beer were available to the average consumer.

“Just lagers and pilsners, or if you were lucky enough and were Irish, you might have experience a stout, but most Americans didn’t even know what that was,” Farguson said. “After the consolidation of the the industry put the focus on two styles, if you were a consumer who didn’t like those styles, guess what, you didn’t drink beer.”

But as craft beer proliferated, a trend again began to occur — mostly towards IPAs.

“We are not a ‘me too’ brewery,” Farguson said.

He hired brewer Bart Bullington, a twenty year veteran of the craft brew industry, in order to make an array of beers — the “Cardinal Sin” red ale, the “Holy Cow” milk stout, “The Convert” lager, “Padre Bravo” brown ale, and “Trespasser” Saison, among others (Absolution also makes both an American and English IPA as well as barrel aged and seasonal brews).

Absolution’s is a broad and ambitious business plan. ABC has a second brewery in Colorado, and according to Farguson already has over 200 large accounts (over $3,000 in sales a month per venue) and is on track to produce 12,000 barrels this year.

But in an industry in which last year’s sale of Ballast Point to Constellation Brands (which makes Modelo and Corona) for over a billion dollars is still reverberating, part of the Absolution plan does not include ever selling out.

“It’s about a legacy. It’s my passion and I love craft,” Farguson said. “I got interviewed for a documentary, and they asked, ‘If Budweiser came to the door knocking, would you sell?’ The first half of my answer is I’ve never had an Anheiser Busch product in my life, and that should tell you the second half — I’m just not going to do it.”

Unity

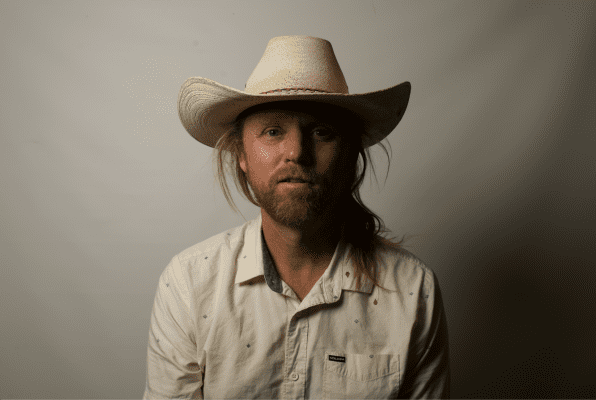

Brewers of the South Bay unite. The 2013 Froth crew: HopSaint Brewing’s Brian Brewer (formerly of Abigaile), Smog City Brewing’s Jonathan Porter, El Segundo Brewing’s Thomas Kelley, Monkish Brewing’s Henry Nguyen, and Strand Brewing’s Rich Marcello. Photo by Lloyd Brown

The Froth Awards began in 2013 as something somewhat different than was intended, which was both an alternative to the “green beer” of St. Patrick’s Day and a competion among local breweries.

The idea was to judge local beers against one another. Local brewers unanimously objected. Henry Nguyen, the brewmaster at Monkish, said that competition was beside the point among South Bay breweries. The breweries are all on the same side.

“‘Best of’ tend to be (to me) a reflection of our American imperialistic values,” Nguyen wrote in an email. “The craft brewing community is very small….Our survival is increased if we support each other. So to compete against one another or be subject to such competition at such a small scale would only hurt the community, not help the community.”

What he was expressing went beyond the event itself. The breweries are so collegial, and so much in agreement that a rising tide will raise all boats, that to newcomers the spirit of cooperation can almost be shocking.

For Shaw, coming from the corporate beer world, it took some time to get used to.

“If we are in a pinch, say you need something, some grains, hops, someone will step up and help you out,” he said. “We had extra lids, and we got a call, ‘Can you spare…’ Not a problem.”

“When I used to work for big business, that was the time to go for the jugular. ‘Oh, you are out of lids?’”

Smog City brewmaster Jonathan Porter said he and his wife, Laurie, chose to bring their brewery here in part because of the existing brewery scene.

“One reason we looked at Torrance was to be close to other breweries,” Porter said. “You know, we are always just helping each other out – it’s good to be in proximity for a lot of reasons, if not just to stop by for a beer or borrow a bag of malts. Like, ‘Hey man, I forgot to order a bag of Cascade. Can you loan me a box?’ ‘Yeah, sure!’”

Porter, whose brewery has become one of the most regionally acclaimed for its Coffee Porter and Saber-Toothed Squirrel amber ale, did sound one cautionary note.

“It used to be, ‘Hey, welcome to LA brewing, don’t do anyting illegal, don’t put out bad beer, and we’lll all get along. We are riding that wave.’”

“It’s continuing, but we’ve got more people coming in, and the support is still there…the only thing that has changed, and this is LA-wide, not just the South Bay, is that it’s, ‘Welcome to the club. But don’t f*** it up for everybody.”

The evolving brewing scene might say something about the larger South Bay community, as well.

Breweries historically came from a sense of place deeply rooted in American culture. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin all brewed their own beer. According to one estimate, in 1870 there were 4,131 breweries in the U.S. Prohibition knocked the number down to near zero in the 1920s. In 1979, there were only 44 breweries in the U.S. By the end of last year, American breweries finally numbered over 4,000 again.

“It’s like we can see our forefathers in each others faces,” said Joel Elliottt, Strand Brewing’s brewer. “…It’s helping bring back the importance of people and their relationships with each other. It’s about pride in the present, and hope for the future.”

Five years ago, there were only five breweries in Los Angeles County. Growth is happening quickly, with more than 30 craft breweries and brewpubs now in LA County. The South Bay is the epicenter of this emergence.

“LA will become the brewing captial of the United States,” Farguson said. “It will surpass San Diego, simply because of of the the size and economics of LA. And I believe the South Bay will be the hub of LA.”

The Third (Occasionally) Annual Froth Awards and Beer Experience takes place March 12 from 1 p.m. to 6 p.m., sponsored by the Easy Reader and Hippy Tree. The day features four bands, seven breweries, and one amazing master chef, Steve Roberts. $45. Ticket includes entrance to the event, seven pours of local craft beer and food pairings. See SaintRocke.com for tickets. See a feature on the bands, headlined by Kira Lingman and the Hollow Legs.