The rescuer: Lifeguard Stephens Troeger was one of the most unheralded of the great South Bay watermen

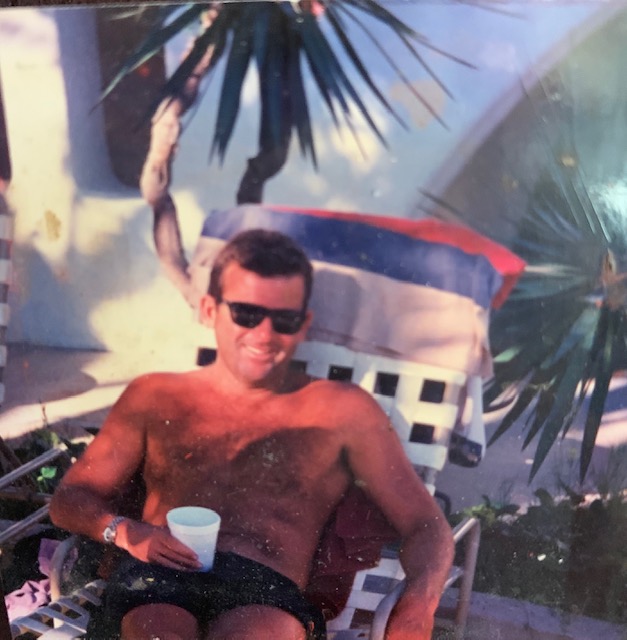

Stephens Troeger at the Redondo Beach breakwater circa 1981. Photo courtesy the Troeger family

A recording used for several years in LA County Lifeguard training documents a call between Stephens Troeger, then the Baywatch captain on Catalina Island, and a team of doctors assisting him in trying to revive a two-month-old girl who had stopped breathing.

People who hear the recording never forget it. The baby was suffering from Respiratory Syncytial Virus, and the infection had grown so severe that her airway was blocked. Applying lifesaving techniques to children is always difficult, but with a child that small — the baby only weighed seven pounds — the procedure, known as rescue breathing, is particularly challenging.

Troeger’s voice is calm, almost unhurried. He asks the doctors for the dosage of a medicine, Albuterol, used to open the bronchial airways, as he carefully continues rescue breathing, narrating his work at regular intervals for the doctors throughout the procedure.

Then, at one point, there is a pause in communication before his voice is heard again.

“This is hard for me,” Troeger says. “I’m sorry if I’m a little broken up. But it’s my own kid I’m working on.”

Troeger was the Baywatch Isthmus captain at the time, which was in 1998. A nurse who lived nearby in the tiny community had responded first and began trying to clear the baby’s airway before calling 911. Troeger knew when the call came over the radio that the baby had to be Saralyn. She was the only two-month-old baby on the Isthmus.

Troeger’s life-saving efforts were successful. His daughter is now 22. The recording of the call was used for several years to demonstrate to lifeguards the level of poise possible in a professional lifesaver.

“It’s just amazing how professional he was throughout the call,” said Mark Montgomery, a lifeguard colleague and longtime friend of Troeger’s. “Talk about distraction — there is no more distraction than that.”

Steve Troeger with his wife Kathy and daughter Saralyn shortly after his rescue of her. Photo courtesy the Troeger family

Over the course of a 31-year lifeguard career that included rising to Baywatch captain both at the Isthmus and Avalon, Troeger performed thousands of rescues. Avalon is one of the most challenging posts in lifeguarding because it attracts so many amateur and professional divers and boat operators and because lifeguards there serve as paramedics to the entire community.

“Besides having to deal with boats all day, they also have to be ready when the bars close at 2 a.m. and people start getting stabbed,” Montgomery said.

“If there was a dangerous and difficult situation, he was the guy you would call,” said John Stonier, who served as rescue boat supervising lieutenant for a large swath of Troeger’s career. “Because he would go for it. He didn’t have a death wish or anything. He just knew he could do it.”

Fellow lifeguard and lifelong friend Brooks Bennett said Troeger was arguably the most skilled Baywatch captain who ever served.

“He was unreal,” Bennett said. “With all due respect to the many captains and skippers of Baywatch for LA County, I can say that Stephen was probably the best one. He knew surfing, he knew waves, he knew swimming, his water IQ was super high, and he was probably the best boatman the county ever had. That is really something to say because that means the best of the best. That’s a huge responsibility to hold, to be a Baywatch captain for LA County for as many years as he was.”

Stonier said Troeger helped save an unfathomable number of lives.

“We were in so many types of situations,” he said. “We rescued everything from boats on fire, boats sinking, boats hitting rocks, airplanes crashing on land and at sea, even on a tow line attached to a cross-channel carrier that had hundreds of people on board.”

“He was the type of guy, if you were ever in an emergency, this is your guy,” said Troeger’s wife of 26 years, Kathy Troeger. “He was one of those people who are able to pull up all the facts in a situation quickly and rely on it, medically. He was so able to keep it together.”

Troeger faced the ultimate test of his poise over the last two years as he endured a painful battle with colon cancer. He passed away on January 24 at the age of 63. But he never lost the larger battle. Right up until his final hours, Troeger kept it together. He also kept those around him together.

His friend Billy Lefay, another former lifeguard, recalled pushing Troeger’s wheelchair up Rosecrans hill just above the beach, near the home where Troeger spent a large part of his childhood as well as the last decade of his life.

“It hurt him too much to walk, so I was pushing his wheelchair, and he says, ‘Well, at least Billy is getting a workout,’” Lefay recalled. “That night he ended up in the hospital, and he never came out. But through the whole thing, he never complained, never showed signs of pain.”

At the hospital, Troeger called his three daughters and his wife to his side.

“Steve Troeger, when it was time to check out, it was like, ‘I’m ready,’’ Kathy Troeger said. “Like, ‘No one interfere. This is what I’m doing.’ He said, ‘Tomorrow is the day. I want to have all my friends over, sneak in some Bailey’s and coffee, and have a little party. And then I’m going to go. Girls, it’s my time.’ He knew it, and he called it. He was such a cool guy.”

“Let’s go big”

Troeger was born into a water-going life. His father John and mother Lynnie owned a 43 ft. schooner named Quissett. The family lived aboard the boat in King Harbor from the time Troeger was 10 years old until he was 14. They lived at the foot of Rosecrans before and after.

Troeger witnessed his first lifeguard lifesaving episode when he was very young.

The Quissett, now known as Coaster II. Photo by Imzadi1979/WikiCommons

John Stonier was a 21-year-old recurrent lifeguard at the time and was a friend of the Troeger family who sometimes babysat young Stephens. One January day Stonier was painting his father’s boat when he heard a shout and looked out towards the water.

“He was just a little tyke, probably five years old, sailing his little sabot at King Harbor, and he flipped it,” Stonier said. “Lynnie was yelling, ‘The boat’s flipped, Johnny!’ He was probably 50 yards from the dock. It was a good swim to grab him and come back. That was one of my first boat rescues.”

It was one of the few times in Troeger’s life he would ever lose control of a boat.

“He was a good sailor, like a little monkey climbing the rigging of his dad’s sailboat,” Stonier said. “He was a sailor from the start.”

Brooks Bennett remembers the first time he met Troeger. They were 10 years old and their parents were meeting. The two boys immediately ran down to the beach and jumped in the water. They’d spent the rest of their childhood years jumping in and out of the ocean together, along with a crew of other boys who included future lifeguards Troy Haley and Mike Cunningham and sailors Jack Tatum and Kelly McMartin.

Bennett, who went through Junior Guards with Troeger, said the Manhattan Beach of that era was idyllic.

“Beach and surf,” Bennett said. “We just lived in Manhattan Beach in a really bitchin’ time as teenagers. It was really cool in the ‘60s and ‘70s. It was heaven on Earth.”

They skateboarded the hills by the beach and had a game they played by the lifeguard substation near Rosecrans, untying the rope to the flagpole and taking turns jumping off and swinging out around the tractors in the lot below.

“It was like, ‘Don’t eat shit, man,’” Bennett said. “And nobody ever did, man.”

They surfed, and surfed, and surfed some more. They started as longboarders and progressed to shortboards as the sport itself changed. Troeger became the most avid among a crew of surf-crazed teenagers.

“Troeger of all people, the big water dog himself, was the one with the first leash,” Bennett said. “He was smart, though. He didn’t want to swim. He wanted to surf.”

The Troegers helped acquaint the whole crew with sailing. Billy Lefay, who was a few years older than the rest, learned how to tie his first figure 8 knot aboard the Quissett. When he was 14, John Troeger let him briefly take the helm of the boat. When Lefay went downstairs to use the head he discovered why — Troeger was eating lobster omelets with his friends.

“He called me ‘Billy Budd’ after that,” Lefay said. “I guess I’ll have to read the book now.”

Troeger played water polo and swam under two legendary coaches at Mira Costa, Larry Bark and Joe Bird. Both were instrumental in his development as a waterman.

“They were great coaches,” Bennett said. “Joe Bird turned kids into robots. They swam major yards. He was just a full-blown grinder.”

Troeger graduated in 1974 and took the lifeguard swim test. He’d always been a good swimmer but not great — strong but not fast.

“A lot of guys who came on [as lifeguards] were all swimmers back in those days,” said Montgomery. “To get in as a lifeguard, it was a race — just a mile ocean swim, mid-winter, no wetsuit. There was no preference given to anybody. Very few guys like Troeger snuck in. It was high school or college swimming finalists, or at least world-class water polo players, not guys like him who just surfed so much.”

Probably because of his own water polo training, Troeger made it. He started the next summer as a recurrent (parttime) lifeguard, and then took a few years adventuring. He spent a year on Hawaii’s North Shore, then a couple of years in Vail, Colorado, skiing and learning to cook in a high-end restaurant. He returned to the South Bay within a few years riding high.

“He was just super solid-looking,” Bennett said. “In Hawaii, his surfing just blew up. He took his surfing to another level. And in Vail he became an excellent skier…. He came back full of himself, really looking good, in really great shape physically, really on his game, going, ‘I am going to lifeguard now.’”

Troeger returned to recurrent lifeguarding but had his sights set on becoming permanent. For three summers in the early ‘80s, he and Bennett were instructors for the Junior Guard program, a South Bay rite of passage for kids who aspire to be lifeguards. They also worked in the El Porto towers, 34th Street, Rosecrans, 41st, 45th, and the Jetty, along with Troy Haley and Eric Atkinson under the supervision of the legendary lifeguard Donny Souther. Troeger worked nights at the Chart House in Redondo Beach and surfed the nearby Breakwall every chance he got.

“He was high on the totem pole at the ‘wall,” Bennett said. “That’s where he spent all his life.”

Stephens Troeger at Avalon.

Finally in the mid-80s Troeger was hired to be a Baywatch deckhand on Catalina Island. It wasn’t a job a lot of people in lifeguarding sought — away from the beach surf scene, on an island, on boats. But it was the job Troeger was made for.

Stonier, who’d helped connect him to Catalina, knew they’d found the perfect guy for the job.

“I was extremely proud of him when he got on as a lifeguard and took any chance I could to get him to be with us on Catalina,” Stonier said. “Because I knew his abilities and skill set. A lot of it was beyond what you could teach, because he’d been learning the ocean since he was a kid. He was a great surfer, a great sailor, a great swimmer. Everything a lifeguard should have, he had, way in advance.”

He had something else that couldn’t be taught, a combination of courage and competence and an ability to unhesitatingly put those qualities into action. Stonier remembered one particular rescue. They’d received a call about an airplane crash in one of the backcountry canyons on Catalina. A man and his son were in a small plane and were intending to airdrop goods to family members who were camping there; unfortunately, instead of flying down the canyon, the man flew up the canyon and crashed into a hill.

“There was no fire when we got there but gasoline was everywhere,” Stonier said. “Steve was the first to get to it. Fuel or not, he just dove in, trying to save the kid on one side of the plane. I went to get the gentleman….But Steve, he just attacked the situation with abandonment. He got to the child through the side of the plane and went to work on him. But because of his heroics, he was saturated with gasoline when he came out. That whole thing could have gone up in flames at any moment. He had a pure lifeguard rescue mentality through and through.”

“He was definitely a credit to the service,” Stonier said. “I chewed him out enough, but I was extremely proud of him all the way through his life because he set out goals and he accomplished them, and how many people can say that?”

Troeger’s next goal was to become a Baywatch captain. But in 1988, something else fell into place. He met the love of his life late one night in the X-ray room at the hospital in Avalon.

Kathy Mullen was an X-ray technician who’d taken a job working weekends on Catalina and after eight months was lured into taking a fulltime job. On the very first night on her new job, she came in for a late night emergency room call. Troeger was the paramedic on the call, and she could tell right away he was trouble.

“He was kind of the big man on campus, that kind of thing,” she said. “It was kind of irritating. He seemed super confident, wore one of those orange zip-up jumpsuits, and all the women at the hospital were like, ‘Oh my god, Steve Troeger!’ We flirted for a while but it wasn’t an instant head-over-heels kind of thing. He was like a ladies man. Obnoxious, but charming. It grew with time.”

They dated for a year but broke up. Troeger in those years was a devoted bachelor. Bennett remembered a nickname his friend acquired in the late 80s and early 90s, “Troegerhoff,” a riff on the hunky star of the Baywatch television series, David Hasselhoff.

“He kind of looked like that — the curly hair, surfer kind of guy,” Bennett said.

Stephens Troeger during his early lifeguarding days.

Troeger went back to work as a lifeguard on the mainland, but he never forgot Mullen. One day he was back visiting Catalina and saw her at a coffee shop. He asked her out and told her, with an honesty that kind of shocked her, that he was convinced that she was the one for him. She relented, got back together with him, then moved back to the mainland to attend USC’s ultrasound school. They were married two years later.

Throughout the next 25 years, there was something Troeger would say so often that it became something of a motto for their life together.

“I was always so worried and so frugal, and my husband’s famous line he would always say was, ‘You’ve got to go big,’” she said. “It could have just been in a restaurant. He’d order the most expensive thing on the menu. ‘Let’s go big. Let’s pretend we don’t have to worry about it.’ He just lived that way. Go big: it was just his thing. People’s finances wax and wane, and you go through your ups and downs, but he just never forgot the important things: ‘Make sure you go big once in a while, because life is what you make of it. Let’s go for it.’”

Troegerfish

A few months after they married, Troeger arrived home to their apartment in Manhattan Beach with big news. He’d been offered the position of captain of the Baywatch Isthmus. Kathy Troeger was already pregnant and her career had begun to blossom back on the mainland, but she didn’t hesitate. They moved back to the island.

“Best decision ever,” she said. “We loved Two Harbors. Miles and miles of roads to run with a baby jogger, a big old organic garden, and a tight community.”

Over the next quarter century, they would live an epic together. They had three daughters: Montana, born in 1995; Saralyn, born in 1997, and Kirra, born in 2003. Troeger rose not only to become captain of Baywatch Avalon but also an important figure both within larger LA County lifeguarding and on Catalina itself.

Rescue boat captain Steve Powell first met Troeger in1996 when he was assigned to be a deckhand on Baywatch Isthmus. He learned very quickly what a different world he’d landed in on the island. Powell had been on the job less than a week when they received a “Mayday” call from a distressed vessel. It was near midnight when they took off aboard the Baywatch.

“It was a very dark and stormy night, just terrible out there on the boat,” Powell said. “They’d pinpointed the mayday on the west end Catalina Isthmus. We headed out around the west end and I was like, ‘Where are we? Oh my god, what is this place?’ I don’t even know how we made it back. I just put my complete faith in Steve.”

During the search, Powell made a rookie mistake. He left the hatch open, letting the rain come in and fry the radar. He felt “like a total knucklehead” messing up on his first rescue. Troeger may have been displeased but he didn’t show it.

“Oh well,” he said. “I can get us where we need to go.”

They reached Cat Harbor but there was no sign of another boat. They were beginning to think the whole thing might be a hoax, Powell remembers, when they turned off the engine so one of them could take a leak.

“As soon as it was turned off, we heard a faint call for help,” Powell said.

“I think it’s a goat,” Troeger said.

“I don’t think it’s a goat,” Powell replied.

They finally laid eyes on the boat, which had crashed on the shore. A man alone with his dog had missed Cat Harbor and crashed further up the island at Lobster Bay. A Coast Guard helicopter was called in as well as a volunteer search and rescue team from the island. The copter couldn’t get to the man, whose dog had died. Finally Troeger sent his new deckhand to go after him.

“It was really hard for me, but he was completely composed,” Powell said. “He said, ‘Tell you what, you’ve got to put on your wetsuit and go in and get that guy.”

They were able to get the man back to the Baywatch boat and over to the hyperbaric chamber on Avalon. Only when the incident was over did Troeger have some stern words for the young deckhand. “It still amazes me that we found that guy without a radar in the middle of the night,” he said. “There’s nobody coming out there to help. You are just out there.”

It was the beginning of a crazy week for Powell, and five years of intense learning under Troeger’s direction.

“It was always like that with him,” Powell said. “Conditions could be really brutal, and you are trying to do a paramedic call on a boat in the middle of the ocean or some extreme rescue out there. It’s difficult, especially with just two people on a boat, so you really need to know what you are doing. It didn’t faze him. He relished going out on those rescues. Like, ‘This is easy. We can handle this.’”

What further amazed Powell was what Troeger got up to on his off days. One of his favorite surf spots was San Clemente, an off-limits, military island.

“It’s black water out there, deep black water,” Powell said. “Man, you are kind of outside everything, 50 miles offshore, overhead waves… It’s a different world out there. Those are not for the faint of heart, but it was no big deal for him.”

Mark Montgomery surfed San Clemente with Troeger, as well.

“It’s where all the great whites hang out. It’s their feeding zone,” Montgomery said. “There’s nobody out there… It’s 25 miles further than Catalina so it’s a pretty good boat ride but when the swells are right, a couple places out there break like Waimea Bay or Mavericks. It’s one of my most vivid memories, surfing with Troeger, just going, ‘Wow.’ You just anchor the boat and paddle out and catch the greatest waves of your life. That’s total Troeger…. ‘Let’s just go big.’”

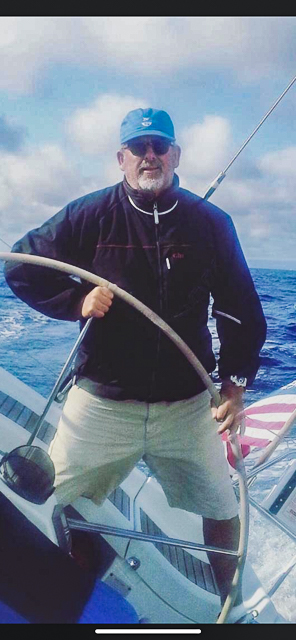

During those years, Troeger also reached some of his biggest accomplishments as a sailor. In 1995, he began crewing aboard Grand Illusion in the Transpacific Yacht Race, which starts at Pt. Fermin in San Pedro and finishes 2,225 miles later in Hawaii. He did the race three times and was part of a winning crew in 2015.

The LA County Lifeguard crew at a hotel in Morocco planning their surf trip. Photo via Facebook/Jay Butki

Montgomery also recalled one of the most epic surf trips in the history of South Bay watermen, which both he and Troeger were a part of. In the late 90s, there was a television show called Eco-Challenge: The Expedition Race which pitted five-man teams against each other in grueling adventure races. In 1998, the show barely avoided disaster when rough conditions in Australia nearly wiped out all the teams, so producer Mark Burnett — one of the pioneers of reality television — decided to bring in the best lifeguards in the world: LA County guards. Chief Buddy Bohn offered 11 guards the opportunity to go to Morocco and get paid rescuing contestants, who kayaked and ocean swam.

“It was 10 to 15 ft. surf,” Montgomery said. “We rescued everyone in the race five, six, seven times. Normally a competitor would be disqualified in the race if you get outside help, but they couldn’t do that this time — you wouldn’t have a race…Steve was on a jet ski making rescues three miles offshore. It was one of the highlights of his later career. They lost 15 kayaks…he’d bring them in and you’d never see the kayaks again. Some of the guys barely hung on; it was 51 degree water and no wetsuits.”

Afterwards the crew had an extra two weeks and the producer gave them three Land Rovers and drivers and they went on trip along the coast of Morocco, surfing and exploring.

“It was just one of the greatest surf trips you can imagine,” Montgomery said.

Steve Troeger with his wife Kathy and daughter Saralyn. Photo courtesy the Troeger family

But by far the biggest accomplishment of Troeger’s life was his family. His girls were his pride and joy. His oldest daughter, Montana, remembers that during her teenage years when most of her peers wouldn’t be seen dead with their dads, she couldn’t help herself — she hung out with him all the time.

“I mean, he was just so lively, so goofy, so funny,” she said. “People get embarrassed by their parents, but he was just so freaking cool it was hard to be embarrassed. He was just a badass.”

Saralyn, the second oldest, who Montana called “his little water polo minion,” likewise was never able to see her dad as anything but cool.

“People always say I am like his only son,” she said. “He loves us all equally, but we all had our own unique dynamic, and I think my dad and I had a bond in that I’m kind of a thrill seeker. I just really do adventurous things, and I carried on the water polo legacy.”

Among her fondest memories are summer sailing trips. The Troegers had a series of boats called Triggerfish. After the family had returned to the mainland for good in 2009, they’d occasionally sail back to Catalina. Her dad’s favorite spot was Cherry Cove, where he and his own mother had long ago planted a “memory tree.”

“He’d point it out to us and we’d go hike to it,” Saralyn said. “A lot of memories are just from those boats.”

Kirra, the youngest daughter, in an unusual way became the most famous of the Troeger tribe. She was born with Down Syndrome, and also born with the Troeger ocean-going gene. Both of her sisters were Junior Guards before her, and when Kirra was 11, she decided she also wanted to be a JG. Kids with her condition often don’t have the strength to take part in ocean swimming, but Kirra proved any doubters wrong — making the cut at swimming pool trials and joining the JG program. She became a waterwoman.

“He passed down some heavy duty water skills to her,” Kathy said. “She’s an amazing swimmer. That was his pride and joy.”

“Yeah, I’m kind of a mermaid, it turned out,” Kirra said. “I’m in the ocean a lot.”

Steve Troeger skippering his 42-foot Beneteau Triggerfish on a sail to Mexico with his family. Photo courtesy of Billy LeFey

Three years ago, Kathy, Steve, and Kirra embarked on a great adventure together: they took TriggerfishV on the Baja Haha, a six-month, 750 mile winter sailing trip down along the Mexican coast and around the Baja Peninsula. Steve had proposed the idea several times, but Kathy had always been reluctant to take Kirra out of school. She finally relented in 2016, and they took off in October.

Kirra said her first reaction was, “What about my friends?” But after a few nights at sea, she found herself happily at home. The only part she didn’t particularly like was the homeschooling.

“The best part was swimming in the warm ocean,” Kirra said. “And my dad would always say, ‘Pools open!’ when he dropped anchor.”

It wasn’t the calm group sail Kathy had expected. Troeger, ever the navigator, didn’t stick close to the coast like most of the group of boats who were on the Baja Haha. They’d go long stretches without seeing other boats, or land. But when the water got rough, Kathy and Kirra were amazed to see that Troeger only got happier. When they rounded the cape and entered the Sea of Cortez, they hit the roughest part of the journey.

“The boat is turning on its side and he’s just throwing his head back laughing,” Kathy said. “We are down below, shaking in our boots.”

After the rough waters came the greatest calm. They also had adventures when they docked, going out for dinners in little Mexican towns. Kirra said one of her favorite things about her dad was his dancing ability. They did a lot of dancing on their adventure.

“He knew like six moves,” she said. “It was a spin, a twirl, a spin and twirl and dip. Five or six things. We would always dance together.”

Troeger received his diagnosis shortly after returning from the Baja Haha in the spring of 2017. He believed until near the end that he’d overcome the cancer. He qualified for cutting-edge treatments that doctors were convinced would work, but the cancer refused to retreat. On that last day, he spent a little time with each of his girls, holding them close and assuring them that even though he was going, he’d never truly be gone. Kirra believes this to be true.

“Like, he’s a stingray, and he’s under the boat, going through us,” she said.

Kathy has been astonished by how her daughters have handled his passing. “He really had an amazing sense of humor and all my girls are super funny,” she said. “Such a nice thing to give your kids. None of them are like, ‘The sky is falling!’ They are like, ‘Prop it up!’ They made me kind of get through this.”

The day after his passing, Kathy composed a letter.

“Dear Cancer,” she wrote. “Just thought I’d write you a letter to let you know the truth. I know that you think you have won, that you think you are taking another one down. I have some news for you. You will never be the victorious one! My amazing husband has fought the battle long and hard with you. He has bravely taken all the hurt, all the pain, and all the insults that you have deviously thrown his way.”

“But guess what?! You can never touch his soul. You cannot negate all the wonderful things and the super person that he still is. You can’t take away his memory etched on the hearts of all his friends, his passion for surfing, his thrill of fresh powder on the mountains, his joy of having the sailboat slice through the water as the wind fills its sails, his ability to find humor in all situations and make tears turn to belly-holding laughter. You can’t hold a candle to the wonderful, caring husband he was to me and father that he is and always will be to his 3 beautiful daughters. They worship him and love him endlessly.”

“You are a lab test, you are a Cat Scan, you are pathology. He was and always will be a warrior, a fierce opponent and at the same glorious time, a gentle giant teddy bear. He is loved and never will that be lost in the decades to come.”

Lefay, his old friend, spoke of Troeger’s legacy. He believes he belongs in the circle of the great South Bay watermen who ever lived. But even more, he marvels at just how well Stephens Troeger lived.

“One of the best husbands, fathers, lifeguards, and friends,” Lefay said. “What a great life.”

A paddle out will be held in honor of Stephens Troeger on March 28. In lieu of flowers, the family requests donations be made to two organizations that help children and young adults with special needs build confidence through water and snow sports, www.Surfershealing.org and www.Bestdayfoundation.org. ER