[Editor’s note: The following is the first in a series of stories on the impact of ultra wealth in the beach cities.]

Manhattan Beach Mayor Mark Burton was canvassing El Porto residents earlier this year about the proposed desalination plant in El Segundo when he stopped to talk to artist Don Spencer.

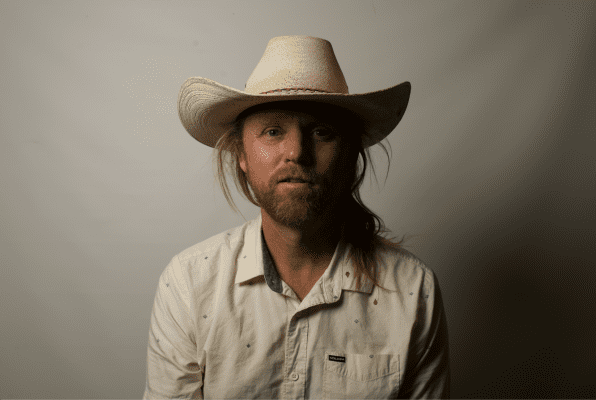

Spencer lives on Crest Avenue, atop a tall sand dune two blocks up from the ocean, in a home he built for himself and his wife in 1990. The house is next door to the home he was raised in, built by his father in 1930. Spencer was born in 1934.

“The surrounding view was bare sand dunes. I have had many exceptional experiences, but no adventure has ever exceeded the quality of my childhood among the dunes,” Spencer wrote in a 2005 Easy Reader story.

Spencer studied art at UCLA and Otis Art Institute and taught art for many years at El Camino Community College. Except for 1978, when he took his family on a cruise down to Mexico and across to the Hawaiian Islands on a sailboat he built in his yard, he has lived his entire life in El Porto.

Spencer’s nostalgic watercolors of post-World War II Manhattan Beach were popular postcards in every downtown drug store and gift shop when the downtown still had drugstores and gift shops.

“I was thinking of all the changes Don must have seen to the town and wanted to know what he thought of them,” Burton recalled of his talk with Spencer. “So, I asked him.”

“He said, ‘Mayor, every day I walk to the downtown Starbucks and I meet the most well-educated, interesting people, the leaders of industry. They’re wonderful people.’”

The response was the opposite of what Burton expected. But he took encouragement from the 82-year-old’s perspective on the city’s transformation in recent years from an upper income to an ultra wealthy community. The influx of millionaires, at least one billionaire and one Forbes cover story subject have altered every aspect of Manhattan Beach, from its schools and politics to its architecture, dining and spiritual life.

Statistics from 2011 to 2015, when the cumulative rate of inflation was 5.4 percent and the rest of the country was struggling to recover from the Great Recession, confirm anecdotal stories about the town’s surge in wealth.

- Average single-family home prices rose nearly 50 percent from $1.4 million to $2.1 million.

- City property tax revenue rose 26 percent, from $20.5 million in $26 million. The 2016-2017 proposed budget projects another 10 percent increase to $28 million.

- Manhattan Beach Education Foundation contributions to the school district increased 20 percent, from $5 million to $6 million. Ed Foundation contributions currently account for 9 percent of the school district budget.

An anomaly among the statistics is the change in median household income. According to U.S. Census data, it rose just two percent between 2010 and 2015, from $139,000 to $142,000, suggesting that the ultra wealthy’s impact on the city is disproportionate to their numbers.

The view from the pulpit

Monsignor John Barry became pastor of American Martyrs Catholic Church in Manhattan Beach in 1983. He had been sent 20 years earlier as a missionary priest to Bellflower, from his home in Cork, Ireland.

“I’ve served in four different parishes in Manhattan Beach, all called American Martyrs,” he observed. The parish’s 1,500 families account for 10 percent of the city’s roughly 15,000 households.

He described his first parish, the one he served upon his arrival in Manhattan Beach, as blue and white collar. Parishioners were tradesmen, teachers, lifeguards, salespeople and aerospace engineers. Many bought at the beach after WWII because they couldn’t afford communities, such as Westchester and the Westside, that were closer to Los Angeles’s downtown business centers.

This was the American Martyrs parish Kevin Campbell grew up in. His dad sold Remington typewriters and adding machines in downtown Los Angeles

“Dad’s co-workers ragged on him for having a 23 mile commute each morning. He’d laugh. He said when he found the beach he thought he’d died and gone to heaven,” Campbell said.

The son attended USC and became a banker. By the early 1990s he was a member of what Monsignor Barry calls his second American Martyrs parish.

Some families had risen from middle income to upper middle income simply because Manhattan Beach real estate had appreciated so dramatically, others because wives had gone to work. Though many of Campbell’s generation could no longer afford homes in their hometown, the financially successful ones could. Still others were products of White Flight. Living close to downtown Los Angeles lost its lustre with the 1988 fatal shooting of a young woman outside a Westwood Village movie theater and the 1992 Rodney King Riots.

Larry Wolf, who co-founded Shorewood Realtors in 1969, said White Flight accelerated with the opening of the 105 Century Freeway the year after the Rodney King Riots. The Century Freeway cut the morning commute to downtown Los Angeles in half. Wolf and his fellow Realtors sold home buyers on the fact that Manhattan’s relatively high prices were offset by not having to pay private school tuition. Realtors didn’t mention that the Century Freeway runs two ways. In 2013, Manhattan Beach Police Chief Eve Irvine addressed a City Council chamber packed with residents concerned about the steady increase in burglaries. The chief told of a career criminal from San Bernadino, 82 miles east on the 105 and 605 freeways.

“We asked him why he kept coming back to Manhattan Beach. He said, ‘Because you lock nothing.’”

Monsignor Barry said his parish’s income ratcheted up a third time during the real estate boom running up to the 2008 financial collapse. Households with earnings over $200,000 rose 64 percent between 2000 and 2010, according to the U.S. Census. If you owned a home in Manhattan Beach during this period and had resisted the temptation to refinance, you were land rich. If you could afford to buy a house you were cash rich.

But not as rich as the American Martyrs’ newest wave of parishioners.

The Monsignor describes his fourth Manhattan Beach parish as increasingly made up of the ultra wealthy, who have been followed to Manhattan Beach by celebrity chefs, such as MB Post’s David LeFevre and exclusive retailers, such as Trina Turk and Italian jewelry designer Roberto Coin, both of whom opened stores in downtown Manhattan Beach last year.

Because of his vow of poverty, Monsignor Barry said he finds himself in a awkward position when parishioners invite him to dine at a downtown restaurant.

Last year Ferrari and Maserati dealerships from Beverly Hills opened locations on Hawthorne Boulevard, near the foot of Palos Verdes, long the wealthiest community in the South Bay.

LA CarGuy’s owner Mike Sullivan has a Porsche dealership there, as well. But like Campbell, he is a Manhattan Beach native with a local’s knowledge of the market. This year he is moving his Porsche dealership to Rosecrans Avenue, the gateway to Manhattan Beach.

“In the past, Porsche had to be at the base of Palos Verdes. Now, there are more Porsche owners in Manhattan Beach,” Sullivan said.

Real Estate numbers

3Leaf Realty owner Jerry Carew, another native of Ireland, began selling real estate in Manhattan Beach in 2001. Each week, Carew charts the three highest priced sales in Manhattan and Hermosa. In 2009, the year after the start of the Great Recession, the three most expensive Manhattan Beach and Hermosa Beach home sales averaged $7.5 million.

Two years later, in 2011, the average was $10.7 million, a 42 percent increase.

Three years later, in 2014, the average was $14 million, an 86 percent increase in five years,

Average Manhattan Beach homes fared almost as well as the high end homes, according to David Kissinger, government affairs officer at the South Bay Association of Realtors.

In 2011, as previously noted, the average Manhattan Beach single family home price was $1.4 million. In 2015 it was $2.1 million, a nearly 50 percent increase in four years.

By comparison, the current average single family home price in the 15 South Bay cities served by the SBAOR is approximately $500,000, one quarter the average of Manhattan Beach homes, according to Kissinger.

Kissinger noted that of the SBAOR’s 4,000 members, 1,000 work primarily in Manhattan.

Realtor Tyler Wolf, the son of Shorewood Realtors’ Larry Wolf, said a recently listed Manhattan Beach Strand home was described on the MLS (Multiple Listing Service) as “livable” — in other words, a teardown. The price was $14 million.

The younger Wolf estimated that one in three high end Manhattan Beach sales are all cash. The median all cash home price in Manhattan Beach in 2015 was $2.36 million, according to the SBAOR MLS data.

Carew explained that cash buyers often refinance after using their cash offer for negotiating leverage. But cash buyers may also see Manhattan Beach real estate, with its double digit annual appreciation, as a safe, high return investment at a time when the five year CD is under one percent.

This theory is supported by a report Carew prepared on the number of Manhattan Beach Strand homes that do not appear to be primary residences. The report compared The Strand homes’ street and mailing addresses.

In Manhattan there are 173 Strand/Ocean Avenue street addresses. The owners of 68 of these properties, or 39 percent, according to Carew’s research, do not use Strand mailing addresses.

The assumption that Strand homes with non-Strand owner addresses are not primary residences isn’t 100 percent reliable. But assuming a 50 percent margin of error, it still suggests nearly one in five homes on the 2.3 mile long Manhattan Beach Strand are vacation homes or rentals.

Last summer, South Bay Brokers abandoned its name to become an affiliate of Sotheby’s International. Over the preceding three decades, the boutique Manhattan Beach real estate office had built a sterling, local reputation in the high end home market.

But according to Jim Van Zanten, who co-founded the office with Jack Gillespie in 1985, a sterling, local reputation is no longer sufficient. To be competitive in the Manhattan Beach market requires a global reputation.

“The Beach Cities and Palos Verdes have become a destination for sophisticated buyers, nationally and internationally. Many of the sales are the buyer’s third or fourth home. Sotheby’s is the strongest name in the luxury home market and has over 700 offices in 52 countries,” Van Zanten explained in a June 2015 Easy Reader interview.

Still, even in a global market, local knowledge is a critical advantage. One longtime Manhattan Beach family has quietly acquired at least six Manhattan Strand homes. Despite their eight figure prices, Manhattan Strand homes have become commodity investments. ER

Future articles on Manhattan Beach Ultrafication will address its impact on architecture, retail and education.