Through a combination of historical accident and the law of unintended consequences, the City of El Segundo has found itself shortchanged when it comes to property tax revenue.

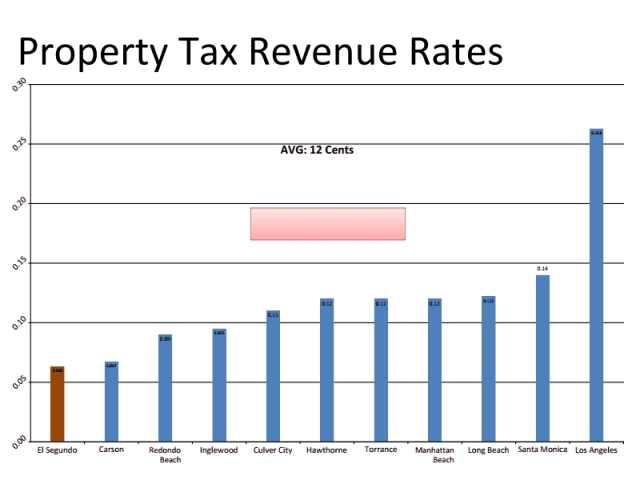

City Manager Greg Carpenter, at the City Council’s behest, presented a short history of the city’s property tax Tuesday night. But he began with a stark fact that is most emphatically in the present tense: El Segundo only receives six percent, or six cents, from each dollar its residents pay in property taxes. This is less than half what most neighboring communities receive and a fraction of the 53 cents on the dollar that goes into Los Angeles County coffers.

“The South Bay average is about 12 percent,” Carpenter told the council. “We are the lowest in the South Bay.”

The city historically kept its property taxes lower than most cities in the state, Carpenter noted, as part of a low taxation ethos that has long been a part of El Segundo. However, when the state enacted Proposition 13 in 1978 – which was intended to reform property tax to control what many perceived as abusively large increases in rates – one of the key components of the law was to wrest control of property taxation power from localities and instead create uniform, growth-controlled rates that would be administered through Sacramento.

It became apparent from the outset that cities with previously low or non-existent property tax rates didn’t receive an equitable share under Prop. 13. El Segundo originally received only 4 cents on the dollar, recalled Councilman Carl Jacobson, who was part of a lobbying delegation as a councilman in the early ‘90s in which cities in similar positions formed a coalition to institute more fairness in tax revenues distribution.

“We ran almost into a stone wall until we included the no-tax cities, then we gained momentum,” Jacobson recalled. “They were able to do something – a little something. Ours went from 4 percent to 7 percent and then came back down.”

Many cities found another route to retain a greater share of property taxes – through the establishment of Redevelopment Agencies, locally-run but technically state agencies (usually comprised of city councils) which enabled cities to target economically underdeveloped areas and keep up to two-thirds of local property tax dollars in a scheme known as “tax-increment financing” aimed at redeveloping those areas.

El Segundo purposefully chose never to go that route. Redevelopment Agencies generally became widely perceived as abusing their original intent as cities scrambled to find creative ways to keep more property tax revenue. Governor Jerry Brown, as part of last year’s budget cuts, disbanded Redevelopment Agencies.

Whatever the historical circumstances, the city now finds itself in a clearly inequitable position regarding property taxes. As Carpenter’s presentation showed, neighboring cities such as Hawthorne and Manhattan Beach both receive twice as much per dollar – 12 cents – in property tax revenue, while Santa Monica receives 14 cents and Los Angeles 26 cents for each dollar its residents pay. Furthermore, the city is a so-called “full-service” city, meaning it provides its own public safety, unlike some cities that utilize county sheriffs or fire departments or have other special tax districts.

“So El Segundo, in a lot of ways, is kind of a worse case scenario as far as property taxes,” Carpenter said.

The question the council grappled with was how to address the inequity. Any reform would require a two-thirds vote by the state legislature, a difficult trick to pull off for any cause, much less that of a city that finds itself in a somewhat unique predicament. Carpenter stressed the issue is not one of tax increases, but rather reallocation.

“We see an unfairness,” Mayor Bill Fisher said. “Of all the cities around us, we are the bottom of the ladder – many are getting much higher returns on property taxes. The question is how to go to Sacramento and convince our representatives – who also represent Manhattan Beach – to say, ‘Hey, Manhattan Beach. We want to take some of this property tax and bring it back to El Segundo.’ It’s going to be war.”

“We’ve got to find a way for them…to put something forward that isn’t just taking money from one city and giving it to another.”

The idea of launching another lobbying effort, similar to what occurred in the early ‘90s, was met with some skepticism by Jacobson, the long-tenured councilman who took part in those fights.

“It would be nice to do,” he said. “I don’t hold much confidence out there that it can be done.”

“Well, it can’t be done if we don’t try,” said Councilwoman Marie Fellhauer.

With other revenues increasingly scarce – particularly in the wake of economically devastating recession and the ongoing diminishment of the aerospace industry – El Segundo is in increasing dire need of the property taxes its residents and businesses generate. Carpenter said that currently the city receives $6.1 million in annual property tax revenue, about 11 percent of overall revenues. Of that, $1.2 million, or 2 percent of total revenues, comes from the 7,700 housing units in the city (averaging $155 per housing unit, with a much higher portion coming from single-family homes, obviously).

“It’s kind of amazing when I pay my property taxes, very little helps run this city,” Fisher said.

Councilman Dave Atkinson had a simple suggestion – fight like hell. He said in the age of social networking, the city could make a bigger noise than in the past about the unfairness of its situation.

“If they don’t listen, with Facebook and everything else….This could become a very hot item over night,” Atkinson said. “If we just sit here and take it like we have all these years, that is exactly what will happen – nothing.”

The council directed staff to begin outreach to other cities in similar straits, and Atkinson and Fisher indicated they’d reach out directly to state representatives. The county, though, with its large share of property taxes, was the council’s first target.

“See what we can do,” Jacobson said.