Hermosa Beach Mayor Stacey Armato probably didn’t have to practice quite as much as mayors past for her State of the City address last week.

That’s because, for large portions of the speech, Armato put the microphone in the hands of the people she said were doing much of the work of keeping the state of the city what it is — which, according to a PowerPoint presentation accompanying her address, is “Awesome!”

High school students, small business owners, and the city’s acting police chief all took their turn at the podium, explaining what they were doing to fix the challenges and preserve the joys of living in Hermosa. Even the audience got involved, with the Beach Cities Health District distributing miniature remote controls that allowed those inside City Hall last Thursday evening to respond to a series of questions, including their likelihood to attend one of the upcoming summer concerts in August (high) to their inclination to serve as a neighborhood watch block captain (low).

The result was an address that downplayed the influence of elected officials while highlighting citizens’ civic-mindedness, and a vision of city government that was transparent and responsive. Armato touted the ways that important decisions unfold in public and, usually, in front of the camera, and encouraged more people to attend meetings of the City Council and various commissions.

“We’re a great community because of our engaged residents, because of our great businesses, our great schools, and our caring staff. The more we hear from you and the more you engage, the more we all benefit,” Armato said.

Her words seemed aimed at addressing some of the more difficult issues Hermosa has addressed in Armato’s tenure: the Greenbelt Infiltration project, and the rebuilding of North School.

Starting last year, South Hermosa residents suddenly became aware of a proposal to build a stormwater infiltration project under the Greenbelt between Second and Herondo streets. After a number of contentious hearings and meetings stretching late into the night, the council eventually decided to try to meet stormwater goals with the construction of a similar project over the border in Redondo Beach.

There is ongoing uncertainty about the Redondo plan, and the Beach Cities recently lost millions in state grant funding intended for an infiltration project because of delays. But many residents living near the proposed location said that they had been taken by surprise by the Greenbelt plan. And while these residents were at times harshly critical of how the city had handled the issue, Armato thanked them in her address and credited them with helping shift the city’s position.

“We heard you on this project. You helped us realize that it wasn’t appropriate for where it was proposed,” Armato said.

The need for civic engagement was especially acute in public safety matters, Armato said.

She spoke less than 24 hours after a fire had destroyed a home under construction on The Strand. Fire officials and city staff said that firefighters were able to respond to the blaze in less than five minutes from the first call about it. Armato brought up Emergency Management Coordinator Brandy Villanueva, who noted a growing, worrisome tendency to post on social media rather than directly contact authorities.

“If you see something, before you start taking pictures and videos, call 911,” Villanueva said. “We can only be as fast as possible if you see something, call us, and tell us something is wrong.”

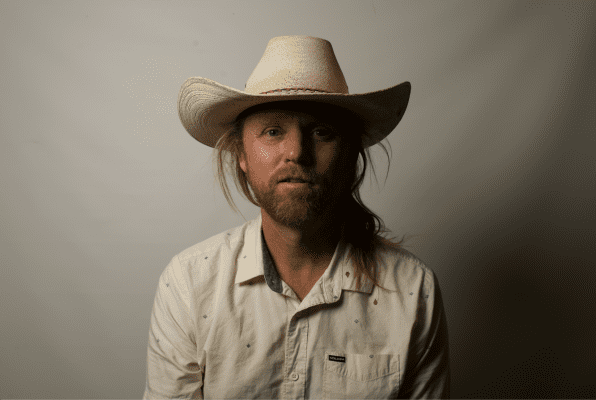

While the focus of the speech was on ways the city enabled residents to get involved, engaging residents also had a more active element to it. Armato touted the city’s partnership with the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health to deploy a Mental Evaluation Team clinician to accompany police officers. And she brought up Acting Chief Milton McKinnon of the Hermosa Beach Police Department, who shared stories of how police had managed to help in three cases of people experiencing homelessness in Hermosa, including a family with a newborn baby that went from living in a tent to an emergency shelter, through work the department did with the charity Harbor Interfaith.

Although those experiencing homelessness may be resistant to accepting help at first, McKinnon said, building up relationships has proven essential to Hermosa’s officers.

“Somebody who says, ‘No,’ ‘No,’ ‘No,’ one day, they’re going to say ‘Yes,’” McKinnon said.