Back to the jungle with Werner Herzog

“The Twilight World,” by Werner Herzog, trans. by Michael Hofmann (Penguin Press, 132 pp, $25)

by Bondo Wyszpolski

Twenty-nine years after the end of World War II, which he thought was still being fought, Hiroo Onoda emerged from the jungle of Lubang Island in the Philippines. He told Norio Suzuki, the young man who’d found him and gained his trust, that he’d only officially surrender to his former commanding officer, Major Yoshimi Taniguchi, who by then—and this is now March, 1974—was 88 years old and selling books in Japan. Taniguchi was brought to the island and finally, for Hiroo Onoda, the war came to an end.

This is, of course, the sort of bizarre tale that would intrigue filmmaker Werner Herzog, and for at least two reasons, the first being that it involves a singular individual (think of Aguirre, Kaspar Hauser, Fitzcarraldo, the composer Gesualdo, and Timothy Treadwell of “Grizzly Man,” to name a few), and secondly that it takes place in the inhospitable jungle (“Aguirre, the Wrath of God,” “Wings of Hope,” “Rescue Dawn,” etc).

Werner Herzog’s novel, “The Twilight World”

Onoda was 22 when he was sent to the Philippines in Dec. 1944. The tide of war had turned against the Japanese but men like Onoda took their orders seriously and did not throw down their guns and run away at the sound of the first shot. Initially, Onoda wasn’t alone, after the larger contingent had left the island. He retreated into the dense undergrowth with Corporal Shimada, and later they were joined by two others, Kozuka and then Akatsu.

Let’s leave them in the jungle for a moment.

The publishers have described this short novel as “part documentary, part poem, and part drama.” They could have added, “and all Herzog.” I’m not sure who added the disclaimer, “Most details are factually correct; some are not.” In other words, this isn’t a biography. For that, you can seek out Onoda’s ghostwritten memoir, “No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War,” the biopic “Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle,” directed by Arthur Harari, as well as countless other retellings. What you won’t get here, except in a brief closing summary, is that after Onoda’s repatriation to Japan he was distressed by his country’s materialism, married in 1976 (his wife, Machie, is still alive at age 85), and spent several years operating a cattle farm in Brazil’s Mato Grosso, before returning to Japan, where he died at the age of 91 on Jan. 16, 2014.

As I began reading “The Twilight World” I thought back to “The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor,” by Gabriel García Márquez, written in 1955 when García Márquez was a young journalist. Luis Alejandro Velasco had been washed overboard on the high seas and ten days later, having drifted on a small raft without food or water, was cast up on the shore. True, 10 days is not 29 years, but it was certainly a minor miracle that he survived. García Márquez embellished the sailor’s tale enough to make it utterly compelling for the readers of his Bogotá newspaper.

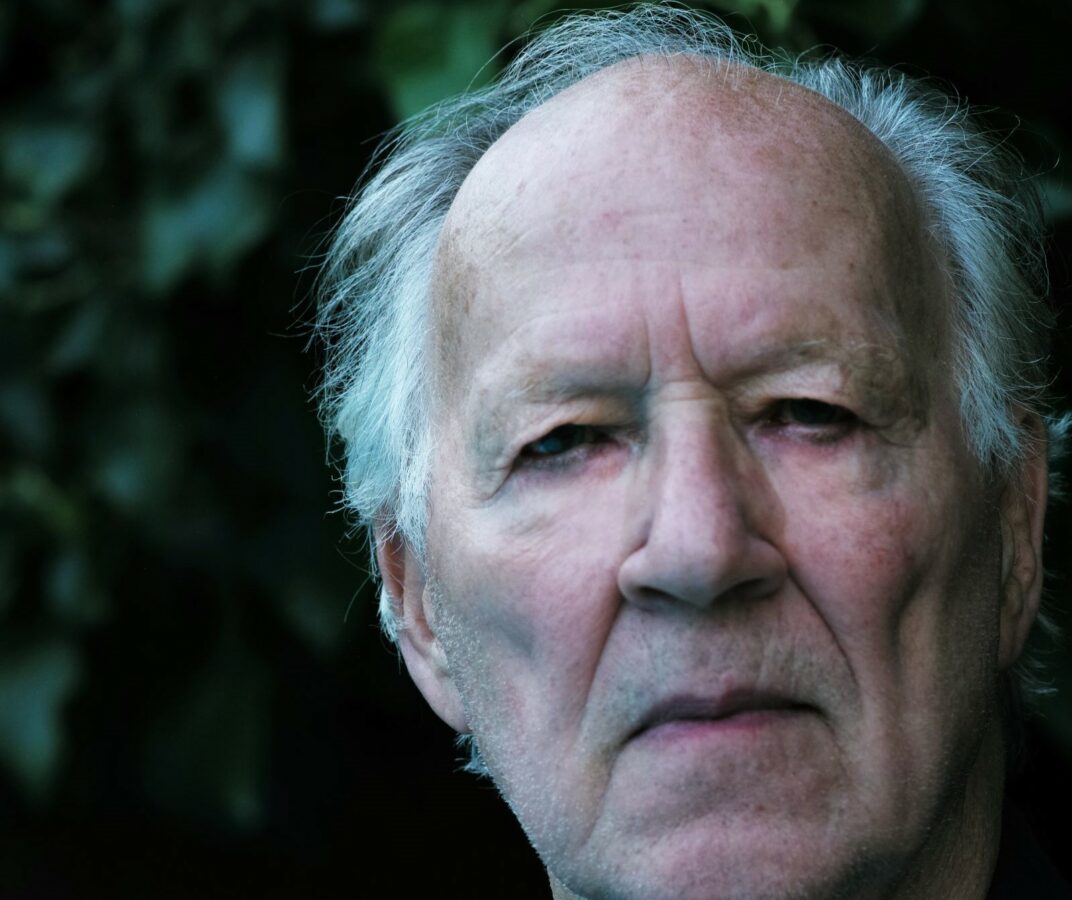

Werner Herzog. Photo by Lena Herzog

Herzog doesn’t say whether he consulted any sources other than Onoda himself, but it’s hard to imagine him not thumbing through the memoir and other accounts. I will point out, though, that Onoda’s jungle is filtered through Herzog’s eyes and imagination. For example, we read early on that “all the crickets scream out at once, in some collective indignation.” Later, they “intensify their monotonous screaming.” He also describes “spiders like disembodied harpists plucking irresistible melodies from their strings.” (second-rate García Márquez, I’m sorry to say!)

Now, if we go back 40 years to Herzog’s prose version of “Fitzcarraldo,” we encounter similar language: “The trees sweat and sleep and doze and grow and fight for the light and lie dormant and in the morning, after a night of rain, they piss, like cows, hundreds of thousands of them, a hundred thousand million. And that makes the birds happy, and they screech, ten times a hundred thousand million.” Twenty years on, in “Conquest of the Useless”: “…stones, hissing in their rage at being jolted out of their inertia, rolled toward the sea,” and “Outside in the darkness four thousand frogs are crying for a savior.” Herzog may claim that he hates the jungle, but it sure provides fodder for his vocabulary.

The four soldiers may be hiding in the jungle of Lubang Island, but their presence is not secret. Periodically they emerge and steal rice from the villagers or to kill their water buffalo for meat. Leaflets are dropped saying, hey, guess what, the war is over, but Onoda thinks it’s a trick. After five years, Akatsu surrenders to Filipino troops. Shimada is picked off, and later, in 1972, Kozuka is killed in an ambush (you can only terrorize the peasants for so long).

How does Onoda know that the war is ongoing? He sees American military aircraft and warships. What he doesn’t realize, however, is that what’s now being fought is the Korean War, and then the war in Vietnam.

He does have several opportunities to surrender, and many more to be killed: “In the thirty years, just under, of his solitary war, Onoda will survive one hundred eleven ambushes.”

The years pass. “Onoda’s war is formed from the union of an imaginary nothing and a dream,” Herzog writes, “but Onoda’s war, sired by nothing, is nevertheless overwhelming, an event extorted from eternity.”

I doubt if Onoda himself would have phrased it like that, but he does wonder, again in Herzog’s words, “Is it possible that I am dreaming this war? Could it be that I’m wounded in some hospital and will finally come out of a coma years later, and someone will tell me it was all a dream?”

To an extent, that sounds more like the author than his subject, the intent being to have us wonder about what’s real and what isn’t, because in this case it’s all certainly surreal. What was it really like hiding out in the jungle for nearly 30 years?

We do not learn much about Hiroo Onoda’s inner life; Herzog’s never been one to psychoanalyze his characters and the viewer often has to take them at face value. But at the end of the novel, when he’s presenting his arms to Major Taniguchi, we do get a kernel of what he may have thought and felt (although the words seem more apropos to Herzog’s Kaspar Hauser).

What Onoda says is, “Sir, there is a tempest raging within me.” ER