Bicycling’s popularity zooms, but will it outlive the pandemic?

Joe Magee and kids Keaton, 3, and Tegan, 6, ride their electric cargo bike to the beach. The Hermosa Beach family bought the bike a year ago so they could leave their car parked on weekends. Photo

Last month, after bike sales soared 300 percent over May 2019, Hermosa Cyclery partners Steve Collins, Ken Lieboewitz, Larry Burke and Mark McNeil stopped selling bikes and stopped answering the telephone. They were out of bikes.

“The phone was ringing every minute. We couldn’t help them,” Collins said. Plus, he and his partners were too busy with rental customers to answer the phone.

When the City of Hermosa closed its Strand, Hermosa Cyclery’s rental business collapsed and the shop laid off most of its 18 employees. The shop is a block off The Strand and a block north of Pier Plaza.

“About half of our rentals are to tourists. But with the hotels closed, we had no tourists. And with The Strand closed, we didn’t want to rent to local families because we knew their kids would be riding in the streets and we didn’t want the liability,” he said.

When The Strand and hotels reopened two weeks ago, one of the partners was stationed at the entrance to the rental area with a clipboard and, like a maitre de in boardshorts, took names of the people in line. The shop’s 100 Schu-eet rentals (named after the shop’s deceased founder Harold Schumaker) rented out as quickly as the orders could be signed.

Hermosa Cyclery’s Steve Collins and Leah Pratley with some of their 100 rental bikes. Photos

Up the street, on Pier Avenue, The Bike Shop’s floor and overhead racks are normally filled with over 200 new bikes. Since shortly after the Shelter at Home order took effect in late March, the store’s floor and racks have been almost bare.

“In a normal year, I may sell 500 bikes. I’ve sold over 250 since the start of the pandemic,” owner Mohammed Seraj said last week. “A guy drove here from Bakersfield to buy a Strand cruiser,” he added in amazement.

After running out of bikes, both shops experienced a surge in repairs.

“People were pulling bikes out of their garages that hadn’t been ridden in 20 years,” Seraj said.

After a few weeks, he posted a sign at his back entrance that read, “We are unable to accept any bicycles for repair.” The sign did no good. Each morning cyclists in need of derailleur adjustments and air prior to setting out on their rides, line up four and five deep.

Seraj and his mechanic Manny Guardoda, who have catered to the whims of obsessive cyclists for over three decades, bring their tools outside and fix what is needed to get the cyclists back on the road.

The Bike Shop owner Mohammed Seraj is almost out of bikes, but is hopeful he will receive a new shipmet this month. Photos

A worldwide surge

Like the pandemic, bike sales have surged worldwide. In the U.S. March sales were double 2019’s March sales, according to the market research group NPD.

The reason is obvious, in hindsight.

“Gyms closed. The beach was closed. Kids couldn’t play soccer. Bicycles are a great machine for exercise and socializing. I’m seeing a lot of families. Parents told me that at first their kids didn’t want to cycle. And now they beg their parents to go on rides,” Seraj said.

But even if bike store owners had foreseen the demand, they couldn’t have ordered more bikes.

In 2019 bike sales were down over 2018, and down again, by 30 percent in the first quarter of 2020, according to a recent New York Times article. That was pre pandemic.

“Last year, bike companies cut back their orders from China to wait out the tariffs. Then, when COVID-19 struck China, the bike factories shut down. Now Trek and AST are saying we might get some bikes for another month,” Seraj said.

Long time cycling advocated Jim Hannon.

Jim Hannon is president of the Beach Cities Cycling Club, a South Bay Bicycle Coalition boardmember and a Blue Zones Project Livability committee member

In 2011, he was instrumental in convincing the beach cities to adopt the South Bay Bicycle Master Plan, the first multi-jurisdictional cycling master plan in the country. It proposed more than 200 new miles of bike-friendly tracks, lanes and roads throughout the South Bay. The award winning Harbor Drive bike path in Redondo Beach, the North Redondo Bike path and the Hermosa Avenue sharrows in Hermosa Beach are among its successes.

Last year, in hopes of teaching cyclists to ride more safely, Hannon’s coalition convinced 14 South Bay cities to divert cyclists who received traffic citations to bike safety classes. The need for bike safety classes is evident from a 2015 state study that found adults account for 84 percent of cycling fatalities, up from 21 percent in 1978.

Hannon said 45 percent of bicycle accidents don’t involve anyone but the rider and 17 percent involve other bicyclists. Of the 18 percent that involve cars, 50 percent are the cyclist’s fault.

Hannon’s current focus is convincing cities to make roads safer for bicyclists.

“To convince more people to ride we need to make riding safer,” he said.

Hannon’s coalition is working with South Bay cities on securing seven grants for restriping street bike lanes and reconfiguring drop off zones at schools in Redondo Beach and neighboring cities.

It is also working on Caltrans ATPA (Active Transportation Programs Applications). ATP grants would make secondary streets safer for SMVs (Slow Moving Vehicles), such as electric bikes, scooters and skateboards.

“Purists look down on electric bikes. I don’t. As people age, people stop riding where it’s hilly. E-bikes keep people riding,” Hannon said.

Hannon believes e-bikes will help sustain the surge in bicycling’s popularity after the pandemic passes.

George Vansickle agrees.

Cocomat plant a tree for every wooden bike bought, creating a truly sustainable form of transport.

Strand Electric bike owner Geoff Vansickle with his Strand Trike, his Fat Tire Mini, which folds to the size of a suitcase, and his Strand Mini.

The electric solution

Vansickle used to race stock cars and motorcycles. In 2015, while recovering from two surgeries and a life threatening illness, the Redondo Beach resident pulled an old bike out of his garage to get some exercise.

“I got about two blocks, hit a hill and was gassed. So I went to Walmart, bought the cheapest mountain bike they had. Found a cheap motor online. Bought a battery and on my first ride rode for two hours. My wife wanted one. So I made one for her. Then the neighbors wanted them and six months later I trademarked the name Strand Electric Bikes.

Last week Strand Electric Bikes, on Pacific Coast Highway in Hermosa Beach, sold 30 e-bikes.

“That’s double the number I sold in my best week last year,” Vansickle said.

Six of the sales were pairs to three older couples. Three were to moms who bought the bikes for their kids.

“Our demographic used to be 45 to 70. Now it’s 14 to 70,” Vansickle said. “It used to be mostly men. Now, it’s 50 percent women.”

“People are getting rid of their cars. I have a teacher who commutes to Compton. A woman who commutes to Marina del Rey. I put three batteries on a bike for a guy who commutes to Malibu. He can travel 100 miles on one charge. Any outlet will recharge the batteries in six hours. With a $200 fast charger, it takes two hours.”

“A bike is always going to be more dangerous than a car,” Vansichle acknowledged. “But drivers are becoming more aware of cyclists and bike paths are getting better.’

Strand Electric mechanic Voc Gregorian sells his bikes as quickly as he an assemble them.

Vansickle is an Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM). He designs and assembles his bikes with parts from Taiwan and China.

The cheapest Strand Electric goes for $900. “It’s for west of PCH. It’s good for kids, but not a hill climber,” he said. His most popular bikes are in the $1,300 to $1,900 range. They have plenty of hill climbing power.

“You don’t want to be going up 17th Street with a kid on the back and dump it. More power is safer,” he said.

Vansickle saw the future of e-bikes last year at the International Cargo Bike Festival in Groningen, Netherlands. When he returned, he made e-cargo bikes for a carpenter, a pizza delivery driver and a photographer who bikes to tourist destinations with his camera and a Canon printer in his cargo box.

Will the surge go unbroken?

Bicycling’s last big U.S. surge was in the early 2000s when Lance Armstrong won the Tour de France seven times. According to CityLab.com, 800,000 people bike to work in the United States. That’s less than 1 percent of the 120 million who drive to work. Portland has the highest percentage of commuter cyclists. But it’s just 2.35 percent. In Los Angeles, .9 percent bike to work.

By contrast, in Copenhagen half of all commuters bike to work.

Seraj sees hope in cycling’s popularity outliving the pandemic in the fact that most of his sales are to recreational and commuter cyclists. During the Lance Armstrong era, the new cyclists were road racers, a narrow niche of riders who fade away without organization and intense commitment.

Seraj’s and the hopes of other cycling enthusiasts are supported by the World Health Organization (WHO), which also sees cycling as one of the pandemic’s few benefits.

“With the inherent positives around cycling during the outbreak – and the fact that many rely on bikes to commute, including key workers – there have been calls to make extra protected space for cyclists during the pandemic, following the lead of cities like Berlin,” the WHO said in an April statement.

John “The Handyman” has trouble keeping up with demand for his restored bikes.

But locally, support for cycling is split.

At the May 12 Hermosa Beach City Council meeting, city environmental programs manager Doug Krauss and city environmental analyst Leeanne Singleton presented a report titled Hermosa Summer Streets.

During the pandemic, their report stated, “Staff has observed a significant decrease in the number of vehicles on the road and increased numbers of pedestrians and cyclists…”

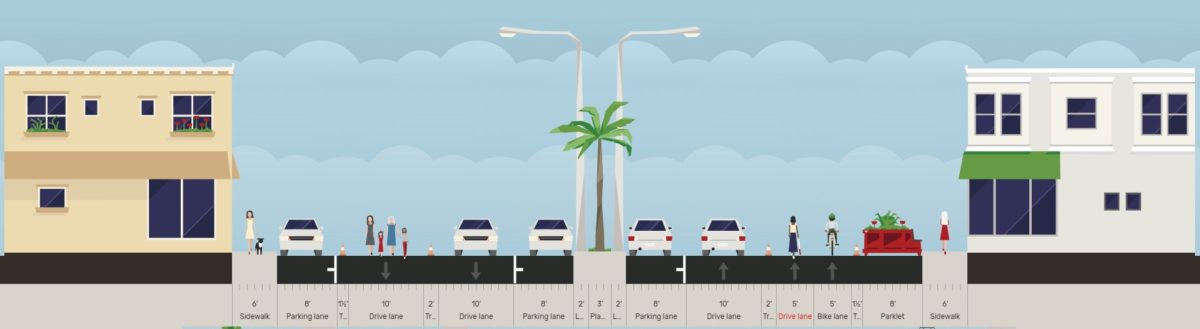

To adjust for the reduced car traffic, the report proposed changing Hermosa Avenue from two car lanes in each direction to one lane in each direction. The two closed car lanes would be dedicated to cycling and walking. The report proposed similar lane conversions on Upper Pier Avenue, Prospect Avenue and the Valley/Ardmore avenues.

Though the proposed changes were to remain in force for just three month, the authors of the report noted, “The program matches the model of ‘living streets…detailed in the city’s General Plan… A living street combines safety and livability, while prompting active, healthy lifestyles.”

A city staff proposal to dedicate one lane in each direction to bicycles and pedestrians along Hermosa Avenue met heated resistance from residents.

The Summer Streets proposal proved polarizing.

“We’re the smallest of the Beach Cities. But we’re the only one with a four-lane road running through our downtown. I think it’s [four lanes] absolutely nonsensical,” resident Raymond Jackson said in support of the plan.

“This proposal is an outrage and reflects a disconnect with every one of your constituents who drives to work,” former Councilwoman Carolyn Petty countered in an email.

“It was done on Pier Avenue several years ago and was a horrible failure. I’m guessing none of the current council members lived in Hermosa then and therefore have no clue,” Chris Prenter said in his email.

Resident Laura Oz argued there are also precedents to support the proposal.

“Please consider closing traffic on Hermosa Avenue from Eighth Street to 16th Street and up Pier Ave to Manhattan Avenue, just like the city has done for the Memorial and Labor Day weekend fiestas and for the St. Patrick’s Day parade,” Oz wrote.

“I’m very happy to see the Summer Streets Program proposal,” Vincent Busam wrote. “I’ve always felt our city needs to re-prioritize the needs of people over the needs of cars, and several of our community streets are over-built for cars. I want to live in a community where I feel safe to let my young children walk and ride their bikes around our small town.”

Council members expressed support for the plan’s concept, but not its execution, at least not now.

“Using bikes and open streets is a great idea,” Councilman Hany Fangary said. “But it’s not the right time for it in my mind.”

The rest of the council concurred. Staff was directed not to pursue aspects of the Summer Streets proposal that involved converting car lanes to bike lanes.

(Additional reporting and David Mendez.) ER