Among high schools, Gardena’s art collection was unrivaled

One hundred years ago, Gardena High School principal John H. Whitely pushed forward an idea that soon put the city on the map. By 1928, according to the Gardena Valley News, GHS was becoming known as “the high school that has the art gallery.”Whitely’s idea was for each graduating class to acquire a painting for donation as a parting gift. It was to be a carefully chosen work, and more often than not by a reputable artist. From the start, the bar was set relatively high. Although many artists were willing to reduce their asking price, the pictures selected were often purchased for what would today be several thousand dollars.

The acquisition of new works had not only persisted through the Great Depression, but also through the lean years of World War II and the enforced displacement of many Gardena residents. Before the war, according to former GHS student Roy Pursche, at least one-third of his classmates were of Japanese ancestry. During the spring and summer of 1942 they were sent to internment camps.

But the tradition that had weathered a national tragedy and a national embarrassment fell silent after the one-time farming community slowly became another L.A. suburb. In 1930, when the rural towns of Gardena, Moneta, and Strawberry Park were incorporated into the City of Gardena, the population topped out at a little over 3,000.

As the 1956 school year drew to a close, the new president announced the end of the acquisition program, and the majority of the collection went into storage. Parts of it resurfaced from time to time, and fortunately a few concerned individuals were always in the wings to help resurrect interest in the collection. One of these people was Phila L. McDaniel, an art instructor at the high school, who curated the permanent collection from 1973 to 1991. In 1993, Janet Perdew Halstead-Sinclair (who graduated from GHS in the summer of 1950) began inquiring as to the health of the collection. She was not pleased with what she discovered, she says today. Apparently the number of artworks exceeded what is currently accounted for: “We originally had 170-plus oil paintings, watercolors, lithographs, and etchings, many of which were left at Peary.”

Not only that, she adds, “Peary personnel obviously didn’t appreciate what they had,” and she notes “the lack of care Peary Middle School treated those (works) left there.” And so, along with Janet Coverly Stapp, Rosemary Parrish Best, and Sandra Gough Haas, Halstead-Sinclair decided to publish a little book about the collection. “To my knowledge, we have been the only alumni to make an effort for the art preservation.”

Halstead-Sinclair and the others were still selling their book until the publication of the “Painted Light” catalogue. “Then my son, Jim Halstead, produced a DVD that we continued selling until Eiko Muriyama came to me in 2009 to ask if we could join forces and become a 501(c)(3) non-profit, which we did, and formed GHS Art Collection, Inc.”

It’s already been 20 years since the work was on view at Dominguez Hills. In 2013, however, perhaps even with an eye on the 100th anniversary of the collection’s beginning, Gardena High School alumni indeed established its non-profit, the purpose of which was to ensure the safekeeping of the collection into perpetuity. It is, after all, the high school’s one invaluable legacy, whether current student body and community are aware of it or not.

Bruce Dalrymple, now living in Palos Verdes Estates, graduated from Gardena High School in 1961. When he was in junior high at Perry, high school classes were completing their last year at the old campus before being relocated a few blocks to the south.

Dalrymple is the president of the board of directors overseeing GHS Art Collection, Inc.

“I became involved when the president at that time, Eiko Moriyama (a former classmate of his), asked if I would be interested in joining the art board. I’ve been on the board for about seven years now. When Eiko had a health issue she had to withdraw from the board and I became president.”

As for his duties or obligations as board president, “I try to coordinate the activities we do,” Dalrymple says. “I keep track of all the people that have shown interest in the collection. I have a lot of help; Simon Chiu is the vice-president, and an art collector. He used to be on the board of the Pasadena Museum of California Art, and he knows the ins-and-outs of the art world.”

Dalrymple says that he himself is not in the art world, although as someone who taught fifth and sixth grade for 36 years he must clearly know how to take charge and delegate authority. His wife, Bea Walker, is the treasurer of GHS Art Collection, Inc., and Janet Halstead-Sinclair is currently a board member as well.

On the face of it, the survival of a large art collection is no small achievement, but for GHS there have been other notable setbacks and a few loses. Two semi-abstract works, one gifted from the summer and the other from the winter class of 1951, disappeared during the 1950s. And, in 1975, an unhappy student set fire to an office and three paintings perished in the blaze.

But even when the paintings were secure they weren’t really safe.

“They had been stored in a vault at the high school for quite a while,” Dalrymple says, “and the vault was not temperature controlled. There were insects in there, so we had to restore those paintings.

“We took them to an art conservator (Eugena Ordonez) who’s really outstanding in her field.”

“They had been hanging in the auditorium at Perry almost continuously since the time they were purchased,” Dalrymple says. “They were painted specifically to hang in those spots because they’re tall and narrow. In 1981, they were both sent to a ‘conservator’ who really didn’t know what he was doing, and he scraped some of the paint off of them and tried repainting them. One of the paintings (the Lauritz) we were able to restore. The other is so damaged that it’s probably going to take a lot of money to get it conserved and saved.”

Or, as curator Susan M. Anderson notes in the new catalogue, “This painting, one of the most prized in the collection, is undergoing extensive conservation and currently cannot be exhibited.”

Brick by brick, or, canvas by canvas

What kind of paintings did the students acquire, and where did they find the works they purchased?

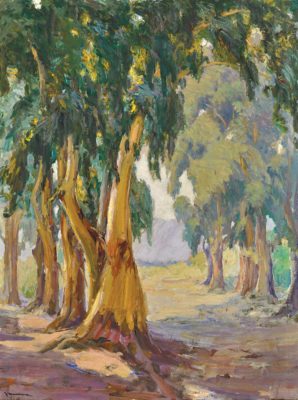

The first work acquired was “Valley of the Santa Clara,” painted a year earlier, in 1918, by Ralph Davison Miller. It’s a verdant landscape, engaging and eye-pleasing, perhaps best described as California plein-air art or California Impressionism. As Anderson writes, “Plein-air painting expressed the artists’ interest in nature, contemplation, process, and quality of life, and became a genuine movement in Southern California–concurrent with and expressive of the ideals of the Arts and Crafts Movement.”

At any rate, Gardena’s ruralness seems to have contributed to the students often choosing to acquire a large number of landscapes and seascapes during the early years. However, the Class of Summer 1930 snatched up Carlo Wostry’s “Beethoven,” which became a perennial favorite among the student body.

Art appreciation was more than a glancing concern at GHS, and student groups were hardly yokels when they visited artist studios in downtown L.A.or in the Arroyo Seco area of Pasadena. They were, of course, guided by their instructors, but one can state that with perhaps only a rare exception they made decent, informed choices. Naturally they weren’t after Titians or Van Goghs, but they did land work by several esteemed artists. For example, Emil Jean Kosa, Jr., won an Oscar in 1964 for his work on the film “Cleopatra”; Maynard Dixon was the husband of photographer Dorothea Lange; and Leland S. Curtis was the official artist for the U.S. Antarctica expeditions, including the one in 1957 that became the first U.S. expedition to reach the South Pole.

In the tenth year of donating art to the school, the acquisition tactics were changed. Whereas small groups of students would visit artists and galleries and then choose a particular work, GHS principal Whitely decided in 1928 to launch the Purchase Prize Exhibit. Now, 80 to 100 artists were invited to send work to the school which would then be on view for two or three weeks. This was in addition to, rather than replacing, the treks by senior class students to various galleries. Now, all the students at the school, without leaving the campus, saw what was being offered and could then vote on their favorite piece. The annual Purchase Prize Exhibit eventually became an important community affair. But who today remembers what it was like?

Through troubled waters

Janet Perdew Halstead-Sinclair does.

“The students were very aware, proud, and involved in selecting a painting for their class gift,” she recalls. “Many of the Class of S’56 have expressed to me their great disappointment in not being able to contribute a painting. You can ask any graduate what painting their class contributed and they can tell you. There was a great sense of pride, and still is today. For the two weeks the exhibit was shown, the seniors of both winter and summer classes would have many discussions on which would be their best choice. At the end there was a class vote.”

Halstead-Sinclair then adds something which appears to undercut the accepted reasons for why the collecting came to an abrupt halt in 1956: “It has been said that they stopped collecting because there was no more space. That is not altogether true. It was because the incoming principal did not want any carry-over of our traditions at the new school.”

Nonetheless, most of the artists in the collection are mere footnotes today, however relevant and feted they were in the California art scene during the early 20th century.

Susan Anderson puts it like this: “During the late 1940s and early 1950s, the art on view would reflect little or no postwar angst or philosophical introspection of the Cold War. The exhibitions featured no avant-garde modernist works or outright political expressions, and none of the artists would be associated with leftist causes. Perhaps this circumspect approach was to be expected at a high school.”

For example, during World War II or just after it, a painting by a Japanese-American artist could have been selected to convey a sense of solidarity or community. Or would that have been deemed too radical?

However, during a Q&A, see below, Anderson pointed out that, although more documentation is necessary (primarily the catalogues that listed the entries each year), “I found evidence that some of the Japanese-American students had modernist works by Japanese artists donated to the collection—perhaps artists connected to the Arts Students League in LA—but there is sadly no sign of the paintings now.”

(Halstead-Sinclair, who arrived at GHS in 1944, isn’t able to comment on what the general attitude was at the school in early 1942 regarding the internment, but “What I do know is there was concern by the faculty as to how some of the students, who had lost brothers in the war with Japan, would accept them. To my knowledge all went well as I never heard of any incidents. I made friends with nearly all the Japanese girls in my class.” And Dalrymple notes that “When [the interned Japanese-Americans] were released from the relocation camps, a lot of people in Gardena were eager to have them come back to Gardena, whereas a lot of other communities were not eager to have them back.”)

And yet, maybe some artistic gambles would have been taken had the gifting not come to a sudden end in the mid-1950s. After all, abstract expressionism was just coming into its own and who knows if a work or two in that genre wouldn’t have entered the collection.

It should be emphasized that none of this speculation is meant to deflect from acknowledging the consistently high quality of the choices that comprise the collection. That said, some of the works are in the middle of an ownership dispute between the school and the Los Angeles Unified School District.

Dalrymple shakes his head: “It was decided in 2008,” he says, “that the paintings that were purchased by the students belonged to the student body. There are other paintings that were gifts from other artists, from individuals and so on. All those paintings the district claims ownership of. But it’s pointed out in the book that these gifts were made for the purpose of being part of the collection.” The dispute is currently ongoing.

Gardena High School’s artistic endeavor inspired other schools (including Mira Costa in Manhattan Beach) to embark on similar programs of art collecting. In that sense, it’s legacy and influence rides alongside the artwork themselves.

Behind the scenes effort

Word of mouth is one thing, but it’s the remarkable new book by Susan M. Anderson that provides physical, tangible evidence of how the program evolved and blossomed. “Gifted: Collecting the Art of California at Gardena High School, 1919-1956” is informative and extremely well-written, and the reproductions of both artwork and historical photos are superb. The book was printed in Germany by Dr. Cantz’sche Druckerei Medien.

Anderson shared her thoughts about how she became involved with the book and the upcoming exhibitions of the GHS collection.

“Simon Chiu, now VP of the board, approached me because of the years I have spent working on projects related to California art and culture. The board started by asking me to write the book. Organizing the exhibition was a secondary, and later, component of the project.”

Anderson was hired in 2015 and worked on the manuscript until it went to the designer in April of 2018. She admits to not having an organized plan when she started.

She’d had previous knowledge of the collection, and even became actively involved when a portion of it was shown at Cal State Dominguez Hills.

“I was invited to speak about California Impressionism and landscape painting in conjunction with the exhibition. But I had heard about the collection previously; I had borrowed works from the collection for exhibitions and had contact off and on over the years with the curator at GHS, Phila McDaniel. It was legendary among scholars and collectors of California art; I first heard about it when I was a graduate student working on an exhibition for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in the late ‘80s.”

In the course of researching and writing the book, Anderson had a number of revelations.

“I was truly surprised at the size of the project that the school took on each year and that they stuck to it for so long in spite of the economic difficulties of the Depression, despite the growth of the student body and the greater size of the senior classes.

“What made the whole project come alive for me was the emergence of the high school scrapbook from the years 1929-1933, some of the prime years of the collection. Without that, it would not have been possible to reconstruct how the project unfolded over the school year or the number of people, 500 to 800, that were necessary to make the exhibition and banquet happen. And the visceral connection to the school through the scrapbook was also (an eye-opener). The fact that it was a leather volume elaborately hand-carved with a decorative Arts and Crafts design was further evidence that I was on the right track with my research, too.”

Initially, Anderson wasn’t impressed with many of the pictures in the collection. Over time, her opinions underwent some changes.

“What surprised me the most was that many of the works I really did not appreciate in the beginning grew to be much more interesting after my study of them. In divining what may have caused the students to collect the work I found that current events played a role in their choices, as well as their opportunity to meet the artists and to grow attached to them personally. The postwar works did not speak to me until I discovered what they were really about.”

A few of the paintings are a little surprising, such as “Show Girl,” by Ted Withers.

“Yes, ‘Show Girl’ was an odd choice, though a masterful work in terms of technique,” Anderson says, “(but) its inclusion is instructive. First, that the students were allowed to choose it at all shows a fairly broad-minded, hands-off approach by the school at that point. When the dominant mode of painting changed in the 1930s from California Impressionism to paintings of the American Scene it opened up choices to the artist. There was more to respond to.” And in turn the students at GHS did exactly that. The final donated pieces had clearly embarked on a different path from the earlier donated works, and where it would have gone we’ll never know.

Halstead-Sinclair is not only “thrilled to see each painting restored and going to three different venues for exhibit,” but says “It truly is a dream come true. Nor did I ever think a book would be published on our little high school’s endeavor of 1919.”

Although she praises the book, Halstead-Sinclair does say that there’s one thing it can’t convey, and that’s “the fact that we students were surrounded by these beautiful works of art everyday. We unknowingly studied and analyzed them until it led many of us into falling in love with them.

“I can’t tell you how overwhelmed I felt the first time (1944) seeing the auditorium filled with beautiful paintings. I just stood there taking them all in, and every time I went to the auditorium for the next six years I felt the same way. Same when I first went into the library. I never ever lost that feeling, which is part of me today. You see, we were born during the Depression, and then WWII came along before we got out of the Depression. Money was very scarce; there was never enough money or gas to take in museums, theater or like events. This was my very first exposure to beautiful creations.”

And it continues today. The current principal of Gardena High School, Rosemarie Martinez, has been actively involved in promoting the importance of what made GHS so distinctive long ago: “I want to be sure that every student leaves knowing about the collection and takes pride in their school’s rich history.”

Nearly the entire collection is going to be on view in three museums. It’s been at the Hilbert Museum of California Art at Chapman University since May, and the closing reception is coming up on Saturday, Oct. 19, from 5:30 to 6:30 p.m. The address is 167 N. Atchison St., Orange. Free parking at Hilbert Museum and 130 N. Lemon. RSVP by calling Craig Ihara at (714) 306-6757 or email him at cihara@me.com.

The exhibition next proceeds to the Fresno Art Museum, Jan. 24 to June 28, 2020, and finishes up at the Oceanside Museum of Art, July 18 to Nov. 29, 2020. Proceeds from Susan Anderson’s stunningly beautiful catalogue will help with future restorations as well as the preservation of the collection. It sells for $43.80, tax included. Shipping and handling is $6.20. Checks can be sent to GHS Art Collection, Inc., P.O. Box 111, Gardena, CA 90248. Online, one can go to ghsac.org/new-products/gifted. PEN