The Thin Green Line: Hermosa Beach police labor group and the city reach a tentative contract deal. Is the dispute really over?

Illustration ©2020 Tim Teebken (www.timteebken.com)

The signs began appearing in early December. They sprouted in front yards throughout Hermosa, like seeds carried by the wind. Businesses put them in windows and along entryways, above cash registers and below displays.

One Sunday, City Manager Suja Lowenthal heard the signs had surfaced in the public right-of-way along Bard Street, near the entrance to City Hall. Lowenthal contacted Milton McKinnon, who was serving as interim chief of the Hermosa Beach Police Department at the time, and told him the signs “needed to be taken down.” Placing unpermitted signs in the public right-of-way violates the municipal code, but Lowenthal likely had other things on her mind.

The signs read “Save our Hermosa Beach Police” and are the most visible signal of a contract dispute between the Hermosa Beach Police Officers Association and the City of Hermosa. Patrol officers and sergeants with the department have been working under an expired contract since July 1. Over the last two months the negotiations, which are typically handled in private conference rooms and commemorated with a little-noticed Memorandum of Understanding, have convulsed Hermosa politics.

After the conclusion of a closed session on at the City Council’s Tuesday night meeting, City Attorney Michael Jenkins announced that the city and the officers association had reached a tentative agreement, calling for a 19 percent increase in base salary. (The announcement came after press time for the Easy Reader’s print edition.) Jenkins said that the council would have the opportunity to ratify the MOU at its next meeting. According a Wednesday statement from the city, the deal also includes retention bonuses and education incentives. The city and the officers association may reopen negotiations in two years, rather than three, “to address recruitment and retention of police officers,” the statement said.

Contract talks have a way of blurring the difference between negotiating bluster and legitimate grievance. The two sides, once miles apart on salary, inched closer during the talks. But the dispute has been sufficiently intense that it is unclear whether a signed contract will have the talismanic power to undo the last two months.

The idea that the HBPD is in need of saving, as the yard signs have it, comes from a concern that shortfalls in the number of officers threaten the department’s viability. At full staffing, Hermosa’s department has 38 sworn positions. But four officers are currently out on injury, and four have left since October. A fifth, three weeks into the department’s field training program, quit two weeks ago. Chief Sharon Papa, out for more than a year on medical leave, officially retired in October. McKinnon, a department captain who served as her interim replacement, left before the new year.

The officers association argues that a higher base salary, the main point of contention in the negotiations, will help Hermosa keep the officers it has, and fill vacancies by making the department more attractive to new recruits and transferring officers.

“We understand that we’re not going to be able to compete with bigger agencies on opportunity. But we have to be able to compete somehow. And if we can’t compete on opportunity, and we’re also 30 to 40 percent behind on pay, nobody’s coming here, and nobody’s going to stay,” said Sgt. Brian Smyth, vice president of the officers association.

The shortages have pressured officers to work extensive overtime, and respond to potentially dangerous calls with little or no back-up. Several officers interviewed for this story described department morale as the worst they have ever seen.

The dispute has had a similarly negative effect on Hermosa’s non-police employees, whose contracts are negotiated by a separate bargaining group, Lowenthal said. When she ordered the signs removed from the public right-of-way on Bard, Lowenthal said was thinking about how planners and engineers and recreation supervisors would react seeing “Save our Hermosa Beach Police” as they arrived for work the next day.

“I’m going to have employees coming to work at 7 a.m. Monday morning seeing this. This will affect their morale,” she said.

Asked if the prolonged negotiations had strained her relationship with the department, Lowenthal hesitated before interim Chief Michael McCrary, who was also in the room, jumped in.

“With the Police Department, no. That’s different than the [Police Officers Association]. My relationship with the city manager is very strong,” he said.

Shortly after the signs appeared, Lowenthal began walking around town, popping into shops that had put up the association’s signs or flyers. She was rewarded for her efforts with at least one business owner asking her why she did not give up her own salary to help fund a raise for the police. The request reveals a broader clash that has animated the contract talks and which will undoubtedly outlive them: a fundamental disagreement about the proper role of local government, and the relative value of the services it provides.

At one negotiating session, Detective Sgt. Jaime Ramirez, the HBPOA president, pointed to the budget of the City of Gardena, the department for which former HBPD Officer Chad Amerine recently left. Ramirez noted that, Hermosa’ revenue per officer is more than twice that of Gardena’s, but Gardena’s officers earn more.

City negotiators responded that the comparison wasn’t logical; some city funds are legally restricted and cannot be put toward salaries. The officers, whose battle at times has seemed as much about the search for respect as boosting numbers on a chart, recalled the response with incredulity, and a touch of the venom that seeps from wounded pride.

“That’s how you do it when you prioritize public safety, versus when you prioritize lamps and murals and all kinds of other garbage,” Smyth said.

Priorities

“Nowhere,” Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., wrote, “is the confusion between legal and moral ideas more manifest than in the law of contract.”

According to the most recent available data from the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, the mean annual wage for a police officer in the United States is $65,400. Of the nation’s 10 metropolitan areas with the highest mean wage for police officers and sheriffs deputies, all are in California. The Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim statistical area, which includes Hermosa Beach, ranks seventh, with a mean annual wage of $104,230.

As in other cities, the officers association and the city have long agreed to use 11 Southern California cities as a set against which to compare salaries. Under the officers association’s existing Memorandum of Understanding, Hermosa has a salary range for officers that starts at $73,212 and tops out at $84,744. According to data from the California State Controller’s office, this puts its starting base pay higher than four of the 11 cities, and its highest level above one of the 11. For sergeants, the starting salary of $92,280 is higher than two of the 11; its top level, $106,836, is higher than one of the 11.

When negotiations between the city and the officer’s association opened last year, the officers sought a raise of 6 percent for each of the next three years, a counter to the city’s offer of 2 percent each year. But, during discussions, Smyth began examining the demographic profile of the department, and grew concerned. Along with the officers who have left recently, 14 are eligible to retire by July 2022, Smyth said. The new information convinced officers to up their demands to a 10 percent increase in salary over each of the next three years.

“I think that’s what opened up everyone’s eyes: We’re down this many guys already, and we have this many people who are going to be eligible,” Ramirez said.

The plan earned the catchy mnemonic of “10 10 10,” and was embraced as a corrective to years without increases in base salary during the Great Recession and the financial cloud cast by Hermosa’s legal battle with Macpherson Oil. City negotiators rejected it.

“Absolutely, it’s unaffordable. Ten-ten-ten would put us in a deficit in year one,” Lowenthal said. (Although often described by the public as a 30 percent increase, it would, because of compounding, be a 33.1 percent increase over current salary.)

For police, “unaffordable” is a relative term. The city has experienced significant growth in property tax revenue over the last decade. For the 2010-11 fiscal year, secured property taxes were $8,918,277; the estimate for the 2019-20 revenue is $15,119,753. This amounts to a growth rate of 6.04 percent per year. Officers have also identified a list of expenses that they consider expendable, including a deputy city manager position that the council created, to some controversy, in the last budget cycle.

The final negotiation session before the impasse was declared took place on Jan. 16. The two sides offer different versions of what transpired. The city, whose final publicized offer was 19 percent over three years, said in a statement that the officers’ association submitted a written offer of three years of seven percent increases after an impasse had already been declared; the officers association maintains it was provided orally before the impasse. As evidence, they cite comments allegedly made by the city’s negotiating team in response to police suggestions about cuts that could be made in the city’s budget, including the unfilled deputy city manager position, to fund the raise.

“The negotiating team told us the council discussed 21 percent in closed session, that they couldn’t get there, that they weren’t willing to make the cuts,” Smyth said.

These events allegedly transpired after the Easy Reader interview with Lowenthal. But in her comments, the city manager was unwilling to cede control over personnel in other departments to the police force.

“If the problem is with police retention and recruitment, we need to look at the police department, and how to solve that issue and the problems it raises without drawing down other departments. The suggestion that this problem can be solved by taking away resources from another department is a nonstarter,” Lowenthal said.

In her frequently voiced view of the daunting complexity of local government, Lowenthal can sometimes come off as a technocrat. “Only the council and I know what it takes to run this city,” she said at one point. But Lowenthal also reveres public service, and bristles at arguments that public employees are overpaid. (Hermosa’s department heads all earned salaries of at least $125,000 in 2018, figures that with pensions and benefits pushed their total cost above $200,000.)

“It is their job to come and advocate for their single issue,” Lowenthal said of the association. “I don’t knock anyone for doing that, I’m actually quite proud of them. They’re doing their job. How they do it might be a little questionable, but they’re standing up for their single issue. What I think is missing is an understanding that the city does not function on a single issue. It is not a single-faceted city,”

McCrary agreed, pointing to a time when he was working in Signal Hill, where he served as both police chief and assistant city manager. He experienced what he called a divided city in which staff were resentful over the resources committed to the police department. Changing that, he said, meant conversations about what makes a community safe.

“We worked to get the officers to understand that putting money in parks, having programs in recreation, all that reduces crime, because kids aren’t out committing crimes. It’s about developing that mindset that we’re all in this together. I would rather have a child in a park program than hanging out on the corner. As law enforcement, that’s all part of crime prevention,” McCrary said.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the tendency toward hysteria about crime among the officers association’s most ardent backers often emerges as concern for threats from the outside: those living distant from services the city could provide. Resident Gregory Kelly said at a recent council meeting that Hermosa’s high property values mean it is especially in need of protection.

“The fact we’re so affluent is another reason why we should have the best police department. There are a lot of communities, somewhere out there, somewhere,” Kelly repeated, shaking his head and pointing to the east, “that aren’t very affluent, and they’re going to come here, and cause us problems.”

Levels of service

Hermosa officers speak to residents outside Trader Joe’s earlier this month. Photo

Throughout the negotiations, the city has maintained there are enough officers to ensure public safety. Despite warnings in officers association mailers about a crime wave, numbers for many offense categories are stable or down. The department’s crime reports urge caution about extrapolating trends from Hermosa’s small sample size.

McCrary said the department has long established “minimum staffing standards.” He declined to disclose what they are, fearful that the information will embolden potential criminals, but said the department has never dipped below them.

“We currently are meeting those and have been meeting them in the patrol operation. We have to fill some of them with overtime currently, because of our shortages, but they are being filled so that the officers are safe on the street. Do we have the staffing I would like? No, we don’t. But we are getting to our calls for service,” McCrary said.

Officers, however, say the minimum staffing standards were never intended to govern deployment for prolonged periods, and that doing so has put officers in challenging positions. Smyth pointed to recent instances of officers having to search houses by themselves.

Matt Domyancic, a Manhattan Beach resident and a retired police officer who specialized in tactical training at multiple departments on the east coast, called an officer searching a house alone “insane.”

“The only cops who usually work alone, period, are state troopers, highway patrol, game wardens: people working in very rural areas. You should absolutely never clear a house by yourself. Even two officers is running thin. If you’re on a call where someone might be in the house, you should have someone in the back, and two or three clearing the house itself. For some of these larger houses, I would want three,” he said.

Domyancic heard about the officers’ labor dispute from Margo Hersey, a Hermosa resident with whom he attends American Martyrs Church. He began speaking with HBPD officers, and grew particularly concerned with staffing in Hermosa’s downtown. There are often three or four officers stationed around Pier Plaza on a Saturday night, but in a recent six-week stretch, there were none, Ramirez said. Eventually, Smyth began filling the shift by himself. Domanycic said the staffing level downtown is “a liability for these officers and the public.”

“Any time you’re dealing with someone intoxicated on drugs or alcohol, you want at least two officers, and that is if there is just one person: one officer engages the suspect, the other watches his back, makes sure no one else is coming up,” Domyancic said.

McCrary acknowledged that the city’s downtown presented staffing challenges. When he arrived, he discovered there were no minimum staffing standards for the downtown detail. He attributed Smyth’s working by himself to his failure to call in other officers, something he and other shift supervisors have the power to do. McCrary said he has since instituted a policy that no officer is to work a weekend night alone downtown.

Forcing officers to work overtime to staff downtown shifts creates its own issues. Officers concede that the detail is considered undesirable. Complaints of burnout are widespread, and it has become difficult to find a replacement for an officer who wants a shift off. Currently, the department has mandated overtime in order to meet minimum staffing on Tuesday nights. Ramirez said the department is getting close to needing multiple nights of mandated overtime.

“Guys who need a day off, their only alternative is going to be calling in sick. And [then] we’d need to order someone in,” he said.

“You want to talk about a morale killer … ” Smyth added.

Tommy Thompson, a former HBPD officer who retired in 2016 after 39 years with the city, said Hermosa’s small department size has long meant that the loss of even a few officers meant overtime obligations could quickly accumulate.

“It was just one of those things where, we knew the position the department was in, and you try to spread it around. Invariably, there’d be one or two people who were affected the most. Lots of departments face that when they’re down officers. You throw in people who are injured, and then the ones who are leaving: The clock is always ticking,” Thompson said.

Shortly after arriving, McCrary began examining logs to get a handle on how much overtime officers were working. For a 13-week period covering October, November and December, the highest total he found was an officer who was averaging 15.4 hours per week of overtime, a figure he called “not excessive for law enforcement.”

“They’re not working excessively in my opinion. But over a period it will have an impact, and I’ll be meeting with them and addressing that issue,” he said.

McCrary has at least one potential fix for concerns about burnout should staffing shortages remain. “I have four detectives I could move in to patrol tomorrow,” he said.

Ramirez said he and some detectives are already working patrol shifts. Increasing that, he said, would further curtail the department’s investigative abilities. He pointed to an incident last month, in which a Hermosa resident was followed home from an area casino, then allegedly held up at gunpoint in his driveway for his winnings.

“To further the investigation, I don’t have the manpower. We could do it, but everyone would have to drop what they’re doing for weeks. It’s surveillance, once you identify the individuals you need warrants: It’s a lot to do. Unfortunately, I had to farm it out to L.A. We’ve done a lot of our own cases in the past, but because of the situation we’re in now, we can’t,” Ramirez said.

Kathy Knoll, owner of Uncorked Wine Shop on Pier Avenue, recalled an incident several years ago when her store was the victim of massive fraud. HBPD officers, she recalled, spent extensive amounts of time poring over records as they built a case.

“If this had happened today, they would not have had the resources to do this. When crime happens, you’ve gotta be fast. And this almost put us out of business,” she said.

The bucket

Signs like this one began appearing throughout Hermosa last month. Photo

HBPD Sgt. Mick Gaglia, who is leading the department’s recruiting efforts along with his other duties, has been attempting to fill one of the department’s vacancies with a new hire. It has not gone well.

“The first recruit quit the first day of the academy,” Smyth said. “So [Gaglia] hired a second. That recruit also quit the first day of academy. He went through the whole testing process, and hired a third. That recruit quit the second day of the academy. So now we’re gaining on it, we’re going to get there eventually,” Smyth said in a moment of gallows humor. “Then he hired a fourth one. That one got into the academy, but three months in, he got injured and had to have surgery. In two years, we’ve hired four people to fill a spot, and we haven’t filled that spot yet.”

The challenge of police recruiting is among the things that the city and the officers association have consistently agreed on. Experts describe recruiting police officers as a nationwide struggle.

A 2010 report from the Rand Corporation compared police officer recruitment challenges to filling a bucket with water, and identified obstacles. First, a “hole” in the bucket is growing from a mixture of looming retirements and a greater tendency among younger generations to try multiple professions instead of sticking with one. Two, the bucket itself is “growing” as communities add to the responsibilities of public safety officers, including tacking on homeland security duties and the expectations placed on officers responding to a growing homeless population.

And third, the flow of the “spigot” filling the bucket is slowing. The Rand report identified national trends among younger generations that will make it difficult to clear even the initial hurdles of police hiring, including increasing rates of drug use, indebtedness and obesity.

Published in 2010, the report came a few years too soon to fully capture the trend that is most frequently mentioned by Hermosa’s officers: shifting societal opinions about criminal justice and law enforcement.

“In my personal experience, changes in laws, [Proposition] 47, [Assembly Bill] 109, all of those have made it much more difficult for police to do their jobs to get the bad guys,” Ramirez said, referring, respectively, to a 2014 initiative approved by California voters and a 2011 state law written to comply with an order from the U.S. Supreme Court. Along with Proposition 57, which California voters passed in 2016, the laws shrunk state’s prison population, reduced the number of offenses that are considered felonies, and expanded parole opportunities for some felons and juveniles, changes law enforcement groups commonly link to increased lawlessness.

Around the same time that the state’s voters approved Prop. 47, a wave of high-profile killings of black men and children at the hands of on-duty officers led to increased scrutiny of police, from would-be muckrakers armed with iPhones, to state legislators wielding new laws. In California, two major bills that faced opposition from law enforcement groups have gone into effect in the last two years: Assembly Bill 392, which modified the circumstances under which police use of deadly force is deemed justified, and Senate Bill 1421, which made public some disciplinary records related to officer uses of force and misconduct.

There is ample evidence that police advocacy groups have distorted the impact of these changes. Studies from the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California and two UC Irvine criminologists have indicated AB 109 and Prop. 47 had no impact on violent crime, but may have led to an increase in vehicle burglaries. Stanford law professor Michael Romano, who co-wrote Prop. 47, has said recidivism rates for those released under the law are far lower than those of the general prison population. Even after the passage of SB 1421, officer discipline records in California remain more difficult for journalists and the public to access than in more conservative states like Texas. But regardless of whether officers are correct in their evaluation, cops clearly feel victimized, and potential cops have been turned off.

“With social media and the way officers are portrayed, people don’t want to enter a career that is full of negativity,” Smyth said.

Increased salary is the most obvious way to increase the incentive for people to become police officers. The Rand report identified compensation as the most widely cited factor for loss of officers. It also offered evidence that departments may have been overestimating its importance, saying that harder-to-measure factors, like a department’s culture, can also be just as important.

McCrary, who has spent decades leading mostly small departments, said pay is critical, and pointed to a new recruitment and retention bonus of up to $40,000 that Hermosa is offering. But he added that money is not the sole factor.

“We need to recruit and hire people who want to work in a small community. Policing is different in Hermosa Beach than in the City of Los Angeles. Officers in L.A., they respond, write a short report, and they’re on to the next call. They’re doing community issues, but that’s really what those patrol officers are doing. Our officers can go out on a call, they can spend time with people, they can follow up on investigations. Our service model is different than a large agency,” McCrary said.

Brian Marvel, an officer with the San Diego Police Department, is the president of the California Peace Officers Research Association, an advocacy group for California law enforcement. He agreed that recruitment posed a challenge, and said that, in the long run, departments could minimize staffing shortages by paying closer attention to demographics.

“You do want a nice flow of younger people coming into the department. Bell curves are what you want in law enforcement. You need those senior officers to be able to transfer experience and knowledge to the younger ones” he said.

But in immediate terms, he said, demographic balance has to give way to public and officer safety. California has some of the most exacting standards for police officer training in the country, which adds to the time and cost associated with taking a recruit from the academy to the driver’s seat of a cruiser. As Gaglia’s experience indicates, it is laden with uncertainty.

“If you get so far down behind the amount of officers that the city has budgeted there is no way you can make it up through new recruits. You need laterals,” Marvel said.

Hermosa’s department, Ramirez said, has not hired a lateral officer or sergeant in a decade. The reason may be pensions.

Tiers

Reading public employee contracts is like looking under the hood of a car: the workings of an older model may be apparent even to the novice, but the closer one gets to the present, the more it seems that the driving force requires special training to understand.

Twenty-five years ago, the section of the memorandum of understanding for Hermosa’s officers association covering retirement contained three sentences. In the most recent contract, it took up nearly three pages, each dense with references to legislation and formulas.

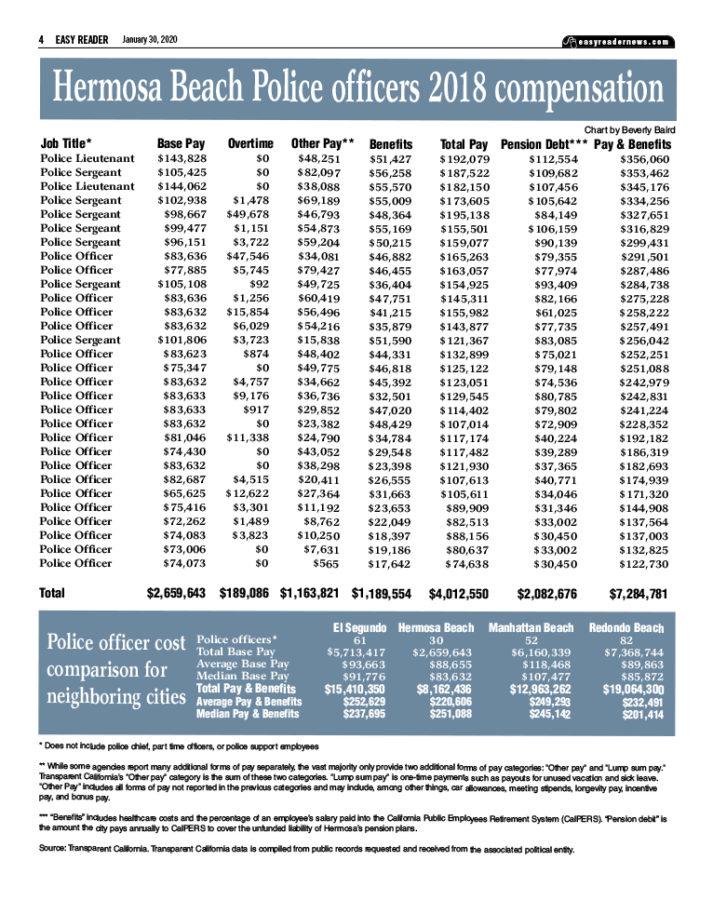

This is a reflection of a calibrated attempt on the city’s part to contain costs. The focus of the current negotiations has been on base pay, but for most Hermosa officers, salary is not the largest expense to the city. In 2018, it represented 36.5 percent of the total cost of sworn, full-time police department employees, apart from the chief. Pensions and benefits, by comparison, represented 45 percent.

Hermosa’s department is not unique in this regard. Cities throughout the state are similarly situated. And for officers joining the department under the new recruiting push, that share may be considerably lower. That is in part because the past 10 years have seen a surge in awareness of public employee compensation, including long-term threats posed by retiree benefit packages.

Some of that awareness is due to Transparent California, a website created in 2014 that displays the salaries of the state’s public employees. Robert Fellner, the organization’s executive director, said the organization was started out of a sense that the public did not understand the cost of public employees.

“What’s been gratifying to see is an explosion in public understanding, especially in the pension stuff. When we started out, it was standard practice just to report salary. A new fire chief would be hired, and the news media would report that ‘His salary will be $177,000.’ And I’d call up and say, ‘Hey Larry,’ or whatever the reporter’s name was, ‘just so you know, that fire chief made $400,000 when you actually include pension and benefits,’” he said.

Transparent California is the work of the Nevada Policy Research Institute, a “free-market think tank” whose funders have included the Charles Koch Institute, the namesake foundation of Charles Koch, late younger half of the Koch Brothers. But while concern with public employee pensions may have conservative roots, it has spread to more liberal circles. Former Democratic San Jose mayor Chuck Reed pushed through pension reform for that city’s employees. And in 2012, California legislators approved the Public Employees Pension Reform Act, which is frequently referred to in the Hermosa officers’ contact, and legislatively limited certain benefits that were once matters of negotiation.

But before Sacramento was curtailing pensions, it was expanding them. At the turn of the millennium, Senate Bill 400 gave California’s public safety officers the option to participate in a far more lucrative retirement package. Instead of a “2 percent at 50,” in which an officer’s pension was calculated by multiplying the number of years served by two percent of final salary, state highway patrol officers and local police would be eligible for “3 percent at 50.” (The “50” is the age at which officers would be eligible to retire and begin collecting a pension.) Starting in 2001, Hermosa officers association contracts included a clause that the city would amend the agreement with the California Public Employees Retirement System, known as CalPERS, to provide 3 percent at 50.

And although Hermosa is now accused of miserliness toward its police officers, it was not so long ago that it was chastised for something closer to profligacy. In 2011, Hermosa was one of five government entities singled out in a Los Angeles County Civil Grand Jury report on pension costs. The report focused on Hermosa’s police benefits plan, which it identified as having the single highest employer contribution rate of any pension plan in Los Angeles County. At the time of the report, Hermosa, along with paying police officer salaries, was committing an additional 62.2 percent of each officer’s salary toward funding pension and benefit costs for department retirees. This was more than twice the average rate at which other Southern California cities were contributing.

The council, stung by being singled out in the grand jury report, commissioned an outside analysis of its pension plans. John Bartel, an actuary whom the city still periodically consults, told the council in February 2012 that its high contribution rate came from two sources. One was payments toward a “side fund,” large unfunded liability attached to the police plan before it joined a CalPERS “pooled risk” plan for smaller cities in 2003, which he attributed to Hermosa’s unusually high level of “industrial disability retirements,” in the years before 2003. (Hermosa did not finish paying off the side fund until last year.) The other was Hermosa’s participation in the 3 percent at 50 plan.

The grand jury report indicated city staff had received “strong policy direction” from the council to modify that plan. As the city and the officers association returned to negotiations, the city managed to extract a pledge to return new hires to the 2 percent at 50 plan.

Ramirez recalled the vote among the members as close and tense. He pointed out that departments that maintained a 3 percent at 50 arrangement would have a distinct advantage in luring experienced officers, who would lose out on such a plan were they to leave.

“I, we, pleaded with them,” he said, meaning himself and Smyth. “We said, Are you stupid? Look at your future. You have to think of the department’s future. But one member said, ‘We’re not here to negotiate for guys who aren’t here yet,’ and he kind of convinced a majority.”

Today, Hermosa has three different tiers of pension packages for its police officers. According to data from CalPERS, the city contributes roughly 10 percent more of an officer’s salary each year for senior cops than for the newest hires. Officers say that this has not contributed to division among the ranks. Unlike the vote on the pension package, discussions among officers have been characterized by unanimity, they say, including the aggressive push for higher salary.

Before the announcement of the 19 percent agreement, Smyth said he was uncertain whether the members of the officers association themselves would vote to approve even the higher, three years at seven percent. But, in describing his vision of what will happen when a contract is finally signed, he seemed optimistic that the disputes of recent months would give way to the enjoyment officers have in being where they are.

“There will be a little downtime, but ultimately everything will pick back up. Everybody who works here likes working here, we just wanted to get this place back on track. If we get a good strong chief in here and we start rebuilding our staffing, with that we’ll rebuild morale,” he said.