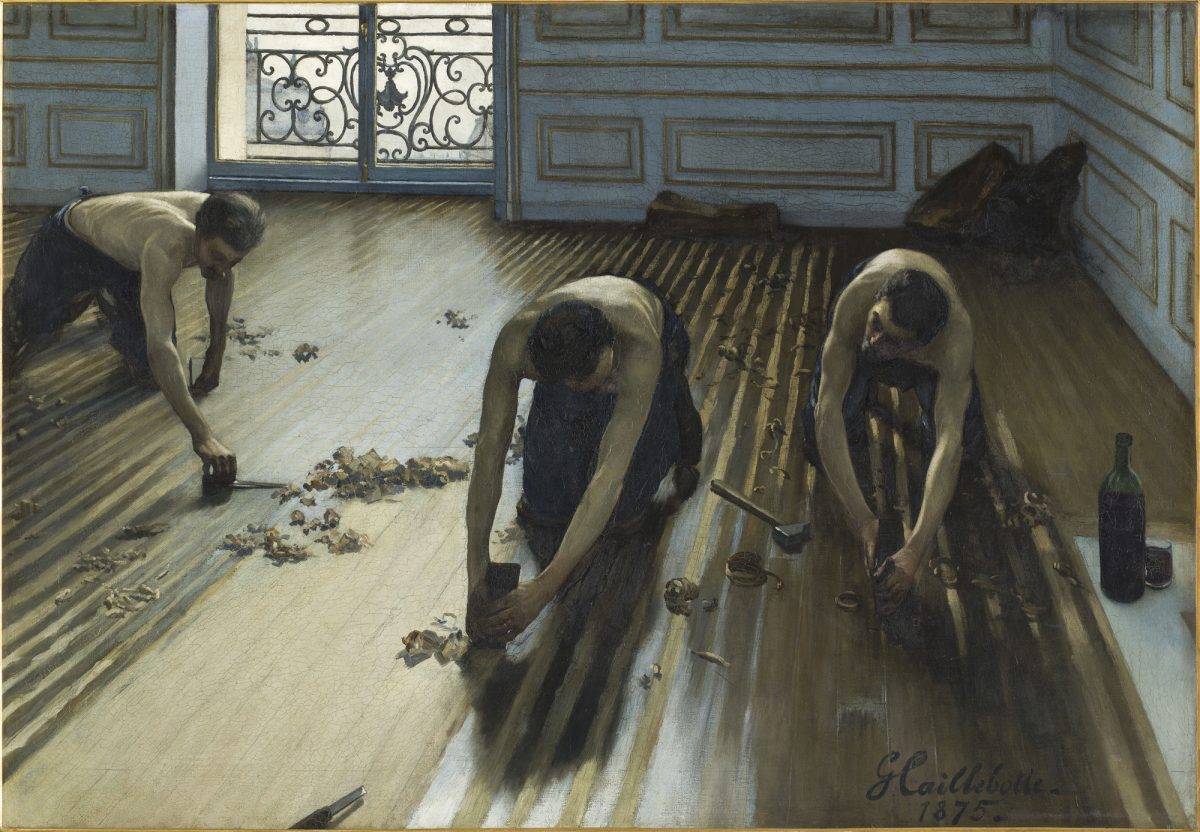

Floor Scrapers, 1875 Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848-1894) Oil on canvas 40 3/16 x 57 1/16 in (102 x 145 cm) Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Gift of the heirs of Caillebotte through his executor Auguste Renoir, 1894 Photo: Musée d’Orsay. dist Grand Palais RMN / Patrice Schmidt EX.2025.2.32

Hanging with the guys

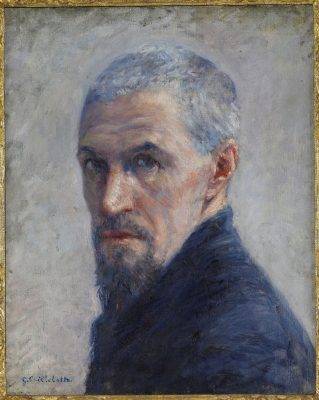

“Gustave Caillebotte: Painting Men” at the Getty Museum

by Bondo Wyszpolski

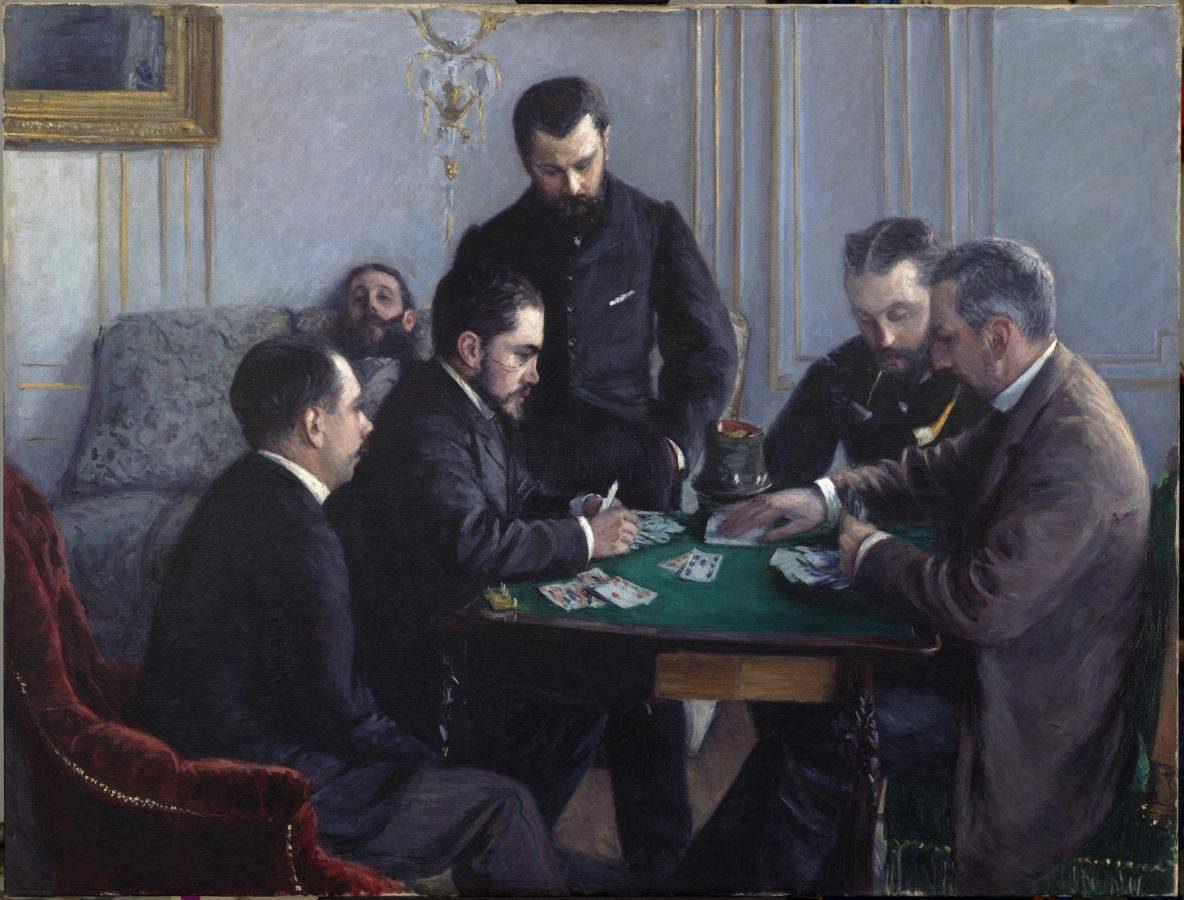

This is an inspired, and inspiring, exhibition, on view through May 25 at the Getty Center. It is also, as one can surmise from its title, a collection of paintings (and drawings) that is focused not so much on Caillebotte’s still lifes, garden scenes, or yachts — except where men are involved.

A specialized view can color the perspective or understanding of the viewer, and in this sense the question of Caillebotte’s sexuality lies on the surface like foam in a beer stein. Whether or not Caillebotte was gay comes up largely because, unlike Manet, Degas, Renoir, et. al., he painted a greater percentage of men and a lesser percentage of women. Many of Caillebotte’s male friends were bachelors, as was he. On the other hand, he lived with Charlotte Berthier for several years, and ensured that she was adequately provided for in his will.

Gustave Caillebotte, born in 1848, died young, at age 45, in 1894. If you studied or even perused Impressionist art during the 1960s and ‘70s, you probably didn’t encounter his name or his work as often as the artists I’ve already mentioned, and perhaps even less than Monet, Cézanne, Seurat, van Gogh, Pissarro, Gauguin, Cassatt and Morisot. At some point, though, especially with retrospectives in the ‘80s and ‘90s, his star began to ascend once more.

I should think that our appreciation of art centers around sensibility free of gender restraints rather than on what is a masculine or feminine work per se. The catalog for the 1995 exhibition, “Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist,” didn’t give that issue much thought. But I did notice, in going through the bibliography (“References Cited”) for the current show, how much has been written in the last 20 or 30 years about Caillebotte’s character and masculinity, most of it speculative, I would add, because Caillebotte didn’t seem to spill the beans about his private life, and to my knowledge neither has anyone else come forward with “revealing” information.

Was Caillebotte resented for his financial independence? I would think very little, because he not only worked assiduously as a painter, he also organized several of the early Impressionist exhibitions, often massaging the heated tempers of his creative friends.

To supplement this, let me quote a few lines by Galina Olmstead in the current catalog: “In the decades following his death, the scope of Caillebotte’s leadership was forgotten and the early histories of Impressionism cast him as a secondary figure. It is only when we recover the significance of his role in the organization of the exhibitions and the corresponding influence they had on his own art that we can begin to see Caillebotte for who he truly was: the quintessential Impressionist, shaped by the group he helped make and that made him.”

But when we enter the gallery, and proceed from one room to another, the works on display simply speak for themselves.

The other main exception is “Man at His Bath,” which shows a man from behind (in both senses) who has stepped out of a bathtub and is now toweling himself dry. It’s a large work and “unsettling” in the present context as it was also disconcerting when first exhibited. It’s not obscene or pornographic, not by a long shot, but it may take us aback, and one can ponder why that is while also viewing “Nude on a Couch,” placed beside it, which depicts an unclothed woman stretched out on a huge sofa. The latter portrait is actually far more revealing, but generally speaking we are more accustomed to seeing nude women on the walls of art museums. I suppose this has a lot to do with “the male gaze,” which has been a hot topic of discussion in recent years.

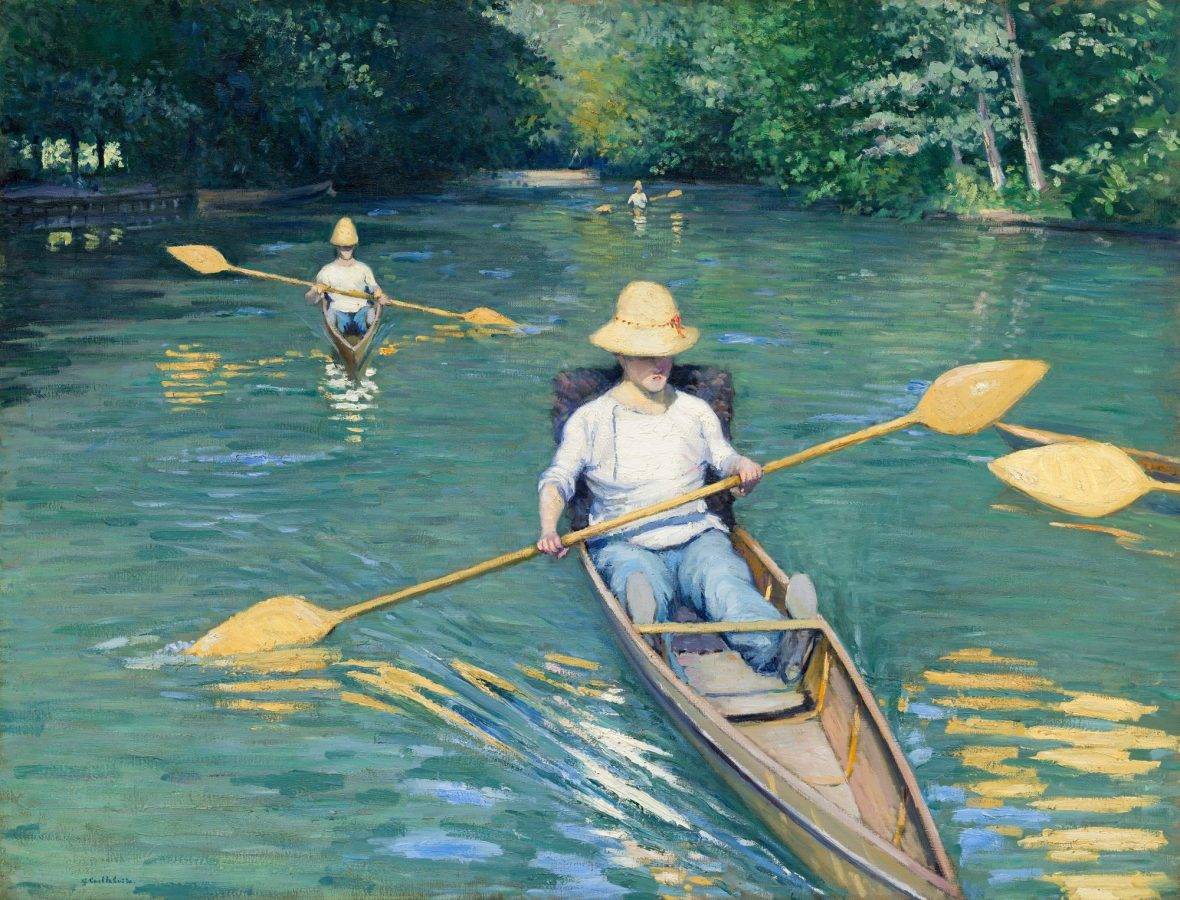

The predominance of boating pictures, men in skiffs or canoes, was due in part to where Caillebotte once lived, near the bank of the Seine in Petit Gennevilliers, and later his interest in yacht racing: He owned and/or built several boats and competed in regattas. His watery scenes, however, are enticing and tranquil. A warm spring day on a lazy river? What could be more seductive?

As one leaves the exhibition there’s a vitrine with a few vintage caps and hats that appear to match those in a few of the portraits. The exhibition in Paris, however, will also include frock coats, a cane, and a work smock, which leads me to think that a decked-out mannequin in period clothing could have enhanced the visual experience. Years ago I set out for Namur to visit the former home, now museum, of the risqué (or blasphemous) Félicien Rops, and apart from the erotic works which could only be examined by first parting and then closing the little red curtains that concealed them, a pair of long gowns were displayed as might have been worn by elegant ladies during the fin de siècle. I was stunned by how evocative they were, imparting a fuller sense of what could only be imagined, framed, in a painter’s portrait.

(If I’d curated this exhibition I’d have hired and attired two or three people in clothes approximating those worn by the man and woman in “Paris Street, Rainy Day” to promenade about the galleries during operating hours… docents in disguise!)

Lastly, two things set the catalog apart from other books about Caillebotte. There is a map of Paris that pinpoints the residences and studios not only of Callebotte and his family, but also those of his friends and fellow artists. And secondly there are short but substantial biographies of these many male friends. They may not be of much interest to the general reader, but it’s all impressively presented and the result of investigative inquiries by Scott Allan and Megan True. And while there are numerous contributors to the catalog, the book itself is edited by Scott Allan in addition to Gloria Groom and Paul Perrin.

In short, it’s all quite breathtaking and of a caliber that brings to mind the Getty’s exhibitions devoted to Édouard Manet and Hans Holbein the Younger, among others. And if you admired those shows, well, what more can I say; you’ll admire this one.

Gustave Caillebotte: Painting Men is on view through May 25 at the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles. Hours, Tuesday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.; Saturday from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m.; and Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Close Monday. Free; but your vehicle will have to cough up the dough. (310) 440-7300 or visit getty.edu. ER

I can’t seem to login –