Manhattan Beach Roundhouse restoration: The boy and the pier

Michael Greenberg speaks at the groundbreaking for the Roundhouse Beautification Project, which he has spearheaded in honor of his son, Harrison. Photo

(Second of two parts. see part one here)

Harrison Greenberg was still a toddler when his mother, Wendy, made an unusual discovery.

He was a hyperactive little boy, bouncy and playful, all go, go, go. He had boundless curiosity; everything he encountered was subject to inspection, but his mind was restless, always moving to the next thing. Early on, while taking her son on early morning strolls, Wendy Greenberg found a place where Harrison’s attention focused to an utter calm: the Roundhouse Aquarium at the end of the Manhattan Beach Pier.

As Harrison would demonstrate for the rest of his life, he was nothing if not hands-on. At the aquarium, he found a rare place in the adult world where his curiosity could run free. He especially loved the touch tanks, where he could put his hands on ocean wildlife, such as sea stars, urchins, snails, and even sharks.

“He was a very curious guy at an early age, so going to the Roundhouse was an opportunity to learn, an opportunity to engage,” Wendy recalled. “He was able to sit there and take in what was told to him. He could touch and learn, which inspired us to go more frequently, with different friends and on different outings.”

Such was Harrison’s enthusiasm for the Aquarium that for his second birthday Wendy brought some of his marine friends to him. She was in the late stages of pregnancy and confined to bed rest, so the family had staff from the Oceanographic Teaching Station — the non-profit which operates the Roundhouse Aquarium — come to their home in Manhattan Beach.

“What better thing could we do on his birthday?” she said. “He was jumping around and happy. It was definitely a birthday party for him. He was fascinated with the animals in the tanks.”

Even the field trips to the Roundhouse with his classmates from Robinson Elementary were special days for Harrison.

“He was one of the lucky few who was able to kiss the sea cucumber,” Wendy remembered. “He was fine with the idea. A lot of the kids would cringe; they thought it was too slimy. He was fine because he’d touched the animal so many times before.”

Harrison’s father, Michael Greenberg, is the co-founder and president of Skechers, the popular, global shoe company based in Manhattan Beach. Although Harrison grew up in affluence, his childhood had its difficulties. He was unruly, and often in trouble. And until he filled out in his teen years, he tended to be pudgy, for which he was mercilessly bullied, especially by one particular kid at Robinson.

Through all those years, the Roundhouse was his respite, the place where he would find the peace of wild things and the seemingly endless possibility of life upon this earth.

“I remember after having his little brother and sister, bringing the little ones along with him, and he would be fully engaged,” his mother said. “He was quite a handful. He would act out and get into trouble constantly. But in that environment he could be happy, and hang out for a long time. You had his full attention if it was something he was interested in.”

As he grew into a young man, that spirit of exploration Harrison found at the Roundhouse served as a runway, a launching pad for all points west. He first fell in love with Catalina Island, exploring its surrounding waters, fishing, often alone in the family’s powerboat. Then his attention turned to Asia, where he traveled more than a half dozen times, sometimes alone, a teenager with a cell phone translator and an unbridled sense of wonder.

It was in Thailand, on April 7, 2015, that Harrison lost his life, choking to death on a late night meal alone in his hotel room while in the midst of a four month internship in China and Southeast Asia. He was 19 years old.

His father rushed back from England, where he had been on business. His first impulse was to go to Thailand, but there was nothing to be done there; he returned instead to Manhattan Beach, to tend to Harrison’s mother and his little brother and sister, Chance and Mackenna. They gathered to try and absorb this unthinkable loss, together.

Even as Greenberg was on his flight across the Atlantic, his mind turned to the question, “What now?” His beloved first born son was gone. He was utterly powerless to do anything about this. His job, he realized, was to help his family learn to live with this new reality, to keep on loving life.

Never is the power of community more apparent than in times of tragedy. He’d barely arrived back in Manhattan Beach when donations started flowing in — a quarter of a million dollars, entirely unsolicited. The Harrison Greenberg Foundation was established immediately.

It often isn’t until the end of a life that we can see the full narrative arc of the loved one who has passed, as if it were a book that had been lived, not written. The story of Harrison was of this ebullient, ruddy-faced little boy leaping in the water, seemingly blossoming overnight into into a square-jawed, handsome and determined young man who’d left middle-aged businessmen at dinner parties slack-jawed with amazement at his quickness of mind, his capacity both for dreaming big and immersing himself in practical details of an idea. He was a third generation entrepreneur; he’d been named after his great grandfather, Harry, a green grocer who’d established a family business in Boston in the 1930s, Belle’s Market, named after his wife. His grandfather, Robert, inherited this entrepreneurial streak, and would start a half dozen businesses before moving to California and founding LA Gear, out of the ashes of which would emerge Skechers. Harrison was a link in the chain, the heir apparent to the family business, which had grown into a billion dollar global enterprise.

But as both Michael and Wendy began the process of remembering, somehow the Roundhouse at the end of the pier was always in the background. The red-tiled building at the end of the pier was more than an aquarium; it represented the gift Harrison had experienced growing up in Manhattan Beach, “this enchanted village,” as Michael thought of it.

Four days after his son’s death, Michael met with OTS officials. He wanted to give back to the community that had given his son such a beautiful life. He knew no better way than to go to the Roundhouse.

“It was just about Harrison, about what we could do,” Greenberg said. “We were laser focused on Harrison, what we could do on his behalf to memorialize him.”

A rendering of the renovated Roundhouse Aquarium, which will be open by this summer. Courtesy Cambridge Seven Associates

The pier

Few towns have as enduring or distinct a symbol as the Roundhouse at the end of the Manhattan Beach pier.

Legend has it a pier was built, before the city existed, by a mysterious figure named Colonel Blanton Duncan. According to lore mined by city historian Jan Dennis, Duncan arrived here from Kentucky during the Civil War. Some old tales indicate he arrived with both slaves and profits from the cotton plantation he’d operated down South; one of the town’s early histories claims he built a small pier in order to smuggle opium in from China.

What is factual, according to Dennis, is Duncan did indeed build the first house in what was to become Manhattan Beach. As nearby and Redondo Beach and Hermosa Beach formed in the late 1800s, the sandy area to the north, all dust and dunes, was considered undesirable — after all, who would want to live amidst all that sand? Duncan paid $1,000 in gold to the Redondo Land Company for 87 and one quarter acres and in 1895 built a mansion on the hill overlooking the scraggly settlement originally known as Potencia. The following year, for $680, he bought another 100 acres that stretched down to the water. It’s clear he built an oceanside structure of some sort, Dennis reports, though it’s unclear if he built a pier.

The city’s first known pier, built around the turn of the 20th century, was a somewhat ramshackle affair, in keeping with the fledgling town itself. It was dubbed “the Old Iron Pier” and fashioned out of railroad ties and timbers affixed with a 900 ft. wooden platform for fishermen.

“Back then Manhattan Beach was just sort of a little village,” Dennis said. “People couldn’t get here because of the dunes…Nobody came here. So they decided, well, we’ll build a fishing pier. That is what it was for — when the Red Car came down from LA, they’d come here to fish.”

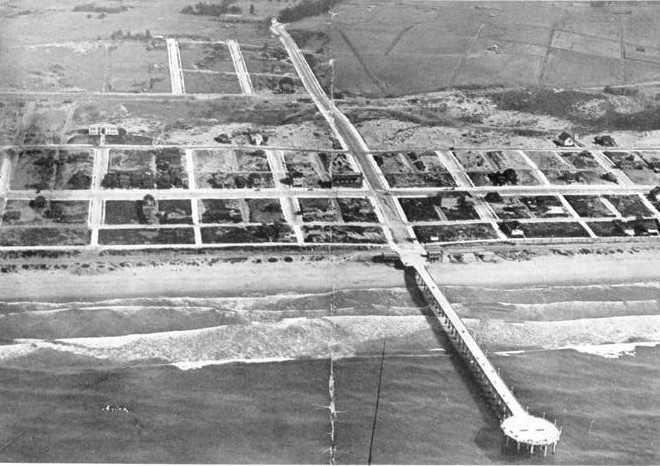

But as Dennis notes in her book, “A Walk Beside the Sea: A History of Manhattan Beach,” the odd little pier quickly became a focal point for many of the town’s activities. Then, in 1913, storms wiped the pier out, and city fathers decided to float a public bond to build a more permanent structure. A proposed $75,00 bond failed in 1914, 168 votes to 170, largely due to a contingent of “Northenders” who wanted it located at the end of Marine Street. In 1916, a compromise was passed overwhelmingly, one that included $70,000 for a pier at the foot of Manhattan Beach Boulevard (then Center Street) and $20,000 for a pavillion at Marine.

Engineer A.L. Harris had the idea for the Roundhouse. “Now in regard to a round end, it is a feature that hasn’t been, as yet, brought out on any other pier along the coast that I know of…another reason for having the circular end is that it is much stronger against the action of the waves,” Harris said at a meeting of the city’s board of trustees.

Material shortages due to WWI delayed its construction but finally the pier and a Roundhouse that looks almost identical to today’s facility were constructed in 1920.

The pier would remain largely unchanged until the 1980s, when Judge Richard L. Fruin established OTS, and the Roundhouse took on a new function as a marine science teaching station. But the pier itself was falling apart; there was a proposal to destroy the entire structure and rebuild. An activist group called Pier Pressure, led by Keith Robinson and Julia Tedesco, fought for its preservation. A 3-2 council vote in 1986 favored restoring the pier rather than replacing it, and in 1991 a $2.39 million project to rehabilitate the pier got underway.

By the time Michael Greenberg met with OTS staff immediately after his son’s passing in 2015, the pier was in most ways flourishing. More than 300,000 people visited it annually, including 15,000 kids who participate in programs at the Roundhouse Aquarium. But beneath the surface, the pier was in a state of deterioration, and the Aquarium’s facilities were being held together largely by the inventiveness of its co-directors, Eric Martin and Val Hill.

“It’s been over 15 years since our last renovation, and things have started to go downhill,” said John Roberts, the chair of the OTS board of directors. “In a marine environment, things don’t last too long.”

Greenberg’s initial notion was possibly to refurbish a tank or two at the Aquarium. But a Greenberg family trait appears to be a certain boundlessness, and as he considered the facility’s needs a bigger idea began to emerge.

“I’m thinking to myself, it’s so dilapidated, it’s so old,” he recalled. “And something triggered the thought, ‘Well, why don’t we put in an entirely new aquarium, and reimagine this aquarium?”

He pledged a million dollars on the spot, in addition to the quarter million already contributed to Harrison’s Foundation. The city, it turned out, already had plans to retrofit the pier itself, and thus a plan was born.

The project

Two remarkable things happened in the 34 months since the inception of the Harrison Greenberg Foundation Roundhouse Aquarium Beautification Project. First, it was fast tracked with almost unprecedented alacrity. Six different governmental bodies, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the California Coastal Commission, signed off on the project in short order; one coastal commissioner actually cried as he voted for the project.

The other unusual aspect is that Cambridge Seven Associates, one of the most prominent aquarium design firms in the world, signed on to do the 2,000 ft. project.

It was unlikely that such a firm would even be interested in so small a project, but after they responded to the Request for Proposals and were selected as finalists, Michael Greenberg had an uncanny feeling as lead architect Peter Sollogub presented Cambridge’s ideas for the Roundhouse Aquarium last January.

Sollogub is a lively, ebullient man, short in stature but large in wonder and imagination. He looks a bit like an American Pablo Picasso. But what struck Greenberg that day was both Sollogub’s passion for this project and his resemblance to someone else — his grandfather, Harry, for whom Harrison was named.

“The passion Peter showed, and knowing Cambridge Seven were the architects for the New England Aquarium and are one of the most world-renowned architects for aquariums around the globe…Yet he said this would the most important project he would work on because of the nature of how it came to be,” Greenberg recalled. “And you know, there was a connection, because I am from New England, and as he is presenting, he reminded me of my grandfather, Harry… I’m thinking, ‘My god, this is meant to be.’” t

Michael spent the early part of his childhood in Boston, and was pulled into the family business as a young boy. He has vivid memories of getting up at 4 a.m. to go to the produce markets with Harry, an indefatigable man who made these pre-dawn runs five days a week and operated his greengrocer’s market seven days a week.

“He was a big part of my growing up,” Greenberg said. “And I felt this deep connection with Peter. Sort of like being guided. It was an easy decision for me.”

Sollogub said it’s the smallest project he’s ever worked on, but also the one that means the most to him, personally.

“Some tanks on other projects are bigger than the entire aquarium in the Manhattan Beach project,” said Sollogub. “Some of our projects are a hundred times bigger, and almost all are many, many times bigger than this project. But this has every last speck of what they have in its little container.”

Cambridge’s other projects include the National Aquarium in Baltimore, Maryland, the Carolina SciQuarium, the Acquario di Genova in Italy and the Ring of Fire Aquarium in Osaka, Japan. But what the Roundhouse Aquarium has that few other facilities do is the immersive quality of being suspended over the Pacific Ocean. Cambridge Seven’s design plays off this quality. The experience of the new aquarium is intended to be akin to walking into the bright blue of the ocean.

A new east-facing entrance will allow visitors to enter an widening corridor that opens up gradually to the Pacific. A rocky reef tank, a sandy bottom tank and a larger version of the popular kids’ touch tank line the left side, and a large shark tank is on the right. The west-facing walls will retain the Roundhouse’s distinct arched windows, so the Pacific is always visible. Above, an updated and enlarged mezzanine will include a goldfish tank, an exhibit space, and a discovery “nook” for small children.

Kids enjoy the touch tank at the Roundhouse Aquarium. Photo courtesy the Roundhouse Aquarium

“The impact of this is really in the heart,” Sollogub said. “When we came down for our interview and went to the aquarium, it really spoke to us. We felt more excitement than many, many projects I’ve had the pleasure of working on over 40 years. There’s something about it. You are out there in this tiny little place, the ocean is coming in from the windows, and the sand, and the tanks all over the place, and the life support systems are in dire need — they are put together, but they need a little help. And the tanks themselves, the animals are being taken care of but could also use a little refreshing…It’s all grown in a little bit of a haphazard way, yet it all works. It’s somehow all cobbled together and you somehow feel, when you are in this special place, this personal touch. And then you remember why this project is happening, and what it is going to be.”

Hill, the aquarium’s co-director, estimated that the facility at some points had been home to as many as 100 species of marine wildlife and, if you count the smaller life forms, as many as a million actual animals. “I’m a plankton person,” she said. “[Co-director] Eric is a whale person. We respect each other’s choices. You can’t have one without the other.”

This interconnection is the overarching lesson of the entire aquarium.

“One of the highlights is the touch tanks,” Hill said. “Kids get to interact with the animals, and with the ocean, really. It gives them a real connection with the animals, and that helps carry on when we bring a message about ocean pollution and pollution prevention and how we all have this connection with something that lives in the ocean.”

“It fosters awareness and love for the ocean, and from that awareness and love people take measures to consider things and not pollute,” John Roberts said. “We’ve done some surveys — some kids who visit live 10 or 15 miles away and have never before seen the ocean. It’s startling but it’s true. How can you protect what you don’t know?”

The rebuilt upstairs of the aquarium will feature an education center as well as photos and videos by Martin, who is a marine photographer, so visitors can experience nearby wildlife too large for the little facility — such as orcas and fin whales and Great White sharks. The project is expected to be completed by Memorial Day weekend.

Everyone involved in the project has been struck by Greenberg’s unrelenting positivity.

“His heart? As big as the aquarium he is leading the way to renovate into a free world class oceanographic teaching center,” said Councilperson Richard Montgomery. “Michael, even through his personal tragedy, has led the way to show us all how to help others less fortunate.”

Dennis, the city historian, expressed gratitude for the Greenberg family’s contribution. But she was also emphatic that people understand that the pier belongs to no single family, but rather is a symbol for the entire city. In a video promoting the Roundhouse beautification project, Dennis tears up as she describes what the Roundhouse means to her when she has been away from Manhattan Beach and returns. “When I see that pier, I am home,” Dennis said. “And I’ve been here 56 years — not as long as some of our natives, but it’s home to me, and the pier is a symbol of it.”

At a groundbreaking ceremony in November, Mayor Amy Howorth said the Roundhouse renovation is also symbolic of the city’s sense of community.

“It really struck me that this speaks to who we are here in Manhattan Beach,” said Howarth. “This is what community does. We come and gather to celebrate the good, and we also stand by each other through the dark times.”

Sollogub said that though the impetus for the project was born from unspeakable loss, the feeling that has presided throughout is one of boundless possibility.

“It’s never been a feeling of tragedy in the room, but really about the joy and wonder of growing up, being young, being wide-eyed looking for new adventure — and at the same time being able to share that experience by taking care of this place, and extending that care and exposure to wonder to the to that experience of underwater life….You leave with more open eyes, and joy. I think that is what this project is about. Wide-eyed wonder.”

Wendy Greenberg knows a little bit about wide-eyed wonder, from the boy she misses so much. The Roundhouse at the end of the pier never fails to remind her of Harrison.

“As much as I try to get away from the problem of losing our son, it’s where I look when I take a dog on a walk — the Roundhouse at the end of the pier,” she said. “When I’m flying on a airplane leaving, I see it. Where I do yoga, there’s a picture of the Roundhouse….It’s the heart of this town.”

The Roundhouse Aquarium remains open in a temporary location in the south pier parking lot. See RoundhouseAquarium.org for more information. For more information on the pier’s history or to order “Manhattan Beach Pier History” or “A Walk by the Sea,” Jan Dennis can be reached at 310-372-8520.

Roundhouse Beautification Project: How to help

The Roundhouse Beautification Project is projected to cost approximately $4 million. The Harrison Greenberg Foundation has donated $1.25 million, the city has allocated $250,000 towards the pier renovation, and another quarter million has been fundraised thus far.

Michael Greenberg said that beyond the $4 million cost of the project itself, the hope is to start an endowment, so that the facility never falls into disrepair again.

“Aquariums require maintenance,” Greenberg said. “The Roundhouse especially so, because it sits on top of the Pacific Ocean, a corrosive environment. What we hope is to keep it looking beautiful. Sustainability is the key word.”

“This is a gift we are bringing to the people of the South Bay,” Greenberg said. “But for people to enjoy it, it should continue to shine, and not become dilapidated. It needs constant love. I am asking for help as much as I can. I am grateful for the gifts from a lot of very generous people we’ve received so far.”

To learn more about the project and how to contribute, see RoundhouseBeautification.com.