“Michelangelo: Mind of a Master”

Before I’d even set foot in the gallery, John Walsh, the Director Emeritus of the J. Paul Getty Museum, confided that he thought it one of the best (maybe the best) installations he’d ever seen at the Getty Center. I’d already read the catalog for the show and, frankly, expected something rather dry. What I quickly realized afterwards is that the book is better suited for those with a specialized interest in Michelangelo but that the exhibition, on the other hand, is for everybody. Paradoxically, the one note that I wrote while lost in the rooms with their subdued lighting, had to do with wondering if we (the common folk, so to speak) were even worthy of being allowed into this “shrine” devoted to an artistic genius.

A strange thing to write, but that’s how I felt.

These 28 works comprise the entire collection of the Teylers’ Michelangelos, and it is the first time that they have, as a group, come to the United States, first to the Cleveland Museum of Art, which organized the show with the Getty, and now to Los Angeles (both of these latter institutions also contributed their own Michelangelo sketches to the show).

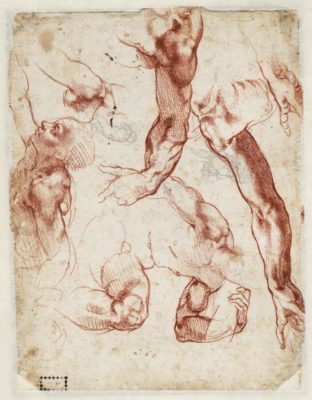

Most of us are familiar with Michelangelo’s marble statue of David, his Pietà, his Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel as well as its ceiling frescoes, but not with the contemplation that preceded them. In a nutshell, then, as Emily J. Peters writes, “Michelangelo’s drawings offer deep insight into his creative process, punctuating every phase of his career spanning the High Renaissance, from his youth in Florence to his later years in Rome … Drawing was the primary tool by which he planned for his many public and private commissions.” Peters, who co-edited the catalog with Julian Brooks, also adds that these sketches prove that “the act of creation was, for Michelangelo, wrought from his prolonged and sustained labor and the processes of repetition, translation, and variation.”

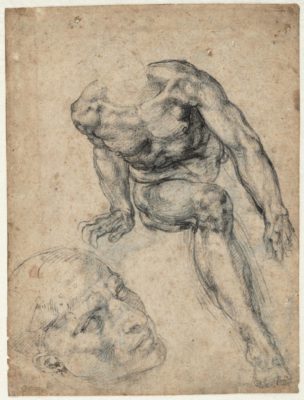

And what was it that preoccupied him most of all? I think it was the human body in motion and the musculature that animated it. As we see with Rubens, born a century after Michelangelo, that human dynamism, often heightened through struggle and pain, was a ceaseless, compelling interest, and it largely inhabits these drawings on view. Michelangelo isn’t sketching sunsets or horses in the meadow; he’s focused on parts of the body and how they appear turned this way and that and how they relate to other parts of the human figure. Not one-hundred percent exclusively, but pretty close.

In “The Last Judgment,” Julian Bell writes, “cloud-banks of pale, naked humanity rise, hover or fall around the damning gesture of a wrathful Christ. Michelangelo’s stock-in-trade, the muscular body, seems not so much an expression of the spirit as an agonizing trap for it, with remorse and disgust convulsing the massed figures.”

For all that, one of the most arresting images in the entire exhibition is not (shall I repeat this?), is not by Michelangelo, but instead by Daniele da Volterra. It is, however, an accomplished portrait of the master at about the age of 75 (Michelangelo, 1475-1564, would live for another decade). The work is displayed alone at the end of a corridor, symbolically eyeing us as we approach. Perhaps in the busiest hours at the museum there will be a line forming in front of it, as there is for Hollywood screen legends, for who wouldn’t want an “audience” with one of the most astonishing artists who ever graced this planet?

The exhibition is accompanied by related events, mostly informal but informative talks by the curators, for those who will understandably want to know more about Michelangelo and the Italian High Renaissance in which he lived, an era that also gave the world the Divine Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci. When we step into the galleries the intervening five centuries simply disappear, and believe me, for an hour or two you won’t miss them in the least.

Michelangelo: Mind of the Master is on view through June 7 at the Getty Center, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles. Hours, Tuesday through Friday and Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., and Saturday from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Closed Monday. Free admission; parking rates vary. (310) 440-7300 or visit getty.edu. ER