Palos Verdes resident Marthe Cohn kept secret her work as a World War II spy behind German lines.

Marthe Cohn at age 19 in 1929. Her blond hair and blue eyes enable her to pass as German, behind German lines. Photos courtesy of Marthe Cohn

“I have always found the right words at the right time,” said 100-year-old World War II spy Marthe Cohn. Her perfect German helped Cohn infiltrate the Third Reich to gather intelligence that helped end the war in Europe. It saved her life in enemy territory and compelled captured soldiers to talk.

The 4-foot-11 Cohn told the POWs that Germany was losing the war, and they would receive better treatment and be able to return to their families sooner if they cooperated. She paced menacingly, pounded her first on a table and forced the prisoners to stand for hours.

“Interrogating them was not difficult. It was not courage,” the Rancho Palos Verdes resident said. “I was given the opportunity to interrogate them, and I was going to do it. I made them talk. That was all.”

Cohn said that she had strength to confront men because her father was a tyrant. “He was a dictator. Fighting with my father helped me enormously because I knew how to fight against a man.”

After the Paris liberation in 1944, she vowed to avenge the Nazi execution of her fiancé Jacque Delaunay, a leader of the French Resistance, and her sister Stephanie’s torture and internment. She joined the French army intending to serve as a nurse but was assigned to work as a social worker.

During a chance meeting with French Colonel Pierre Fabien, Cohn mentioned that she spoke German. He implored her to become a spy because France desperately needed German intelligence. In addition, women would arouse less suspicion than men.

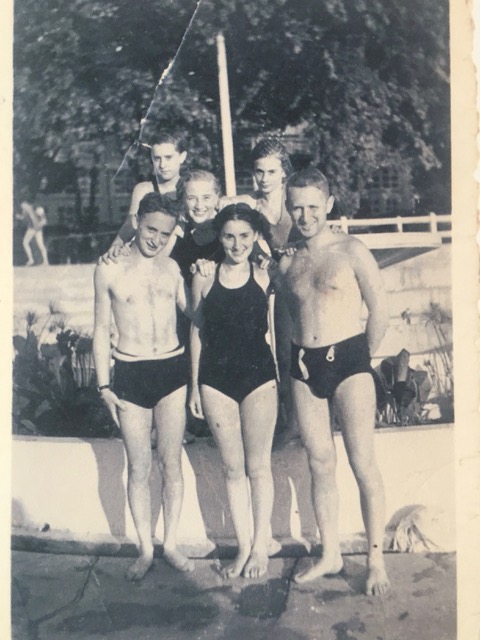

5) Marthe Cohn with five of her six siblings in their hometown of Metz in 1936. Marthe is third from the left.

Cohn’s Orthodox Jewish family, the Hoffnungs, lived in the French region of Alsace-Lorraine, which the Germans had annexed for nearly 50 years before the war. Blonde with blue-green eyes, Cohn easily passed as Aryan.

“Chichinette: The Accidental Spy,” a documentary about her spying, won the Audience Award last year at the Israeli Haifa Film Festival. Her 2002 book, “Behind Enemy Lines: The True Story of a French Jewish Spy in Nazi Germany,” co-written with Wendy Holden, recalls Cohn’s youth in a family of seven children, the Nazi occupation of France and her spy missions. On her 15th reconnaissance, Cohn crossed enemy lines into Germany using the alias Marthe Ulrich, a German nurse searching for her missing German fiancé. She was almost shot when French soldiers mistook her for a German spy.

Marthe Cohn with French soldiers after a Bastille Day/French National Day military review.

“There were times when I was afraid, but it never lasted too long because I had to answer to people. I was able to get out of trouble by talking,” Cohn said. “When your life is in danger, you find the right thing to do.”

By eavesdropping on soldier and civilian conversations, Cohn ascertained Hitler’s plan to abandon the Siegfried Line (fortifications along Germany’s western frontier) and to ambush the Allies in the Black Forest. Cohn walked, cycled and hitchhiked through enemy territory to relay this intelligence to Allied commanders.

Marthe Cohn receiving the Cross of the Order of the Merit in 2014 at the German Consulate General in Los Angeles for helping to “bring an end to WWII and defeat the Nazi regime.”

For her valor, the French army awarded Cohn the Croix de Guerre. The citation praised her “rare courage well beyond the ordinary and astonishing physical resistance.” Later she earned an additional star. The accompanying citation praised her as a “young French woman of exceptional courage. . .who provided military information of the greatest importance, which facilitated to an extraordinary extent the success of the last operations of the French Army.”

After the war ended in Europe, Cohn stayed in the army — over her mother’s protests. She went to French Indochina for the South-East Asian theater of World War II “because there was still so much to do.” Cohn set up field hospitals and learned to administer anesthesia by reading a manual.

Cohn returned to civilian life in France in 1948. While continuing her nursing studies in Geneva, she met an American medical student, Major Cohn. Five years later, they married in the United States. After living in five different states they settled in Rancho Palos Verdes in 1979. Major earned a Ph.D. in biochemistry and became a director of research in anesthesia and neuroscience. Marthe became a nurse anesthetist and worked as her husband’s research assistant.

Decades passed and Marthe’s exploits as a spy remained a secret — even to her family. Without documents, she thought no one would believe her.

Marthe Cohn’s book has been translated into French and German,

In 1998, Marthe traveled to the military bureau in France to obtain army papers because she wanted to apply for dual citizenship. Archive officials were shocked to learn this diminutive woman played such an important role in WWII. They urged her to apply for the Médaille Militaire in 1999, the country’s highest military honor. A year later at the Beverly Hills Sofitel Hotel, surrounded by family and French dignitaries, Cohn shed tears when awarded the Médaille Militaire, the same medal awarded to Winston Churchill.

Over the following days, international news crews in satellite trucks camped on Marthe’s street to interview the accidental spy, recalled Michael Potter, a former Cohn neighbor and an executive producer of the documentary on Marthe. “She was a media sensation,” Potter said.

Reflecting on Cohn’s book, which has been translated into French and German, Potter said, “Marthe is very meticulous, and she wanted everything to be exactly right. She didn’t want any parts to be romanticized.”

“Marthe is a very driven, determined person. But that explains why she took these amazing risks. She’s fearless,” Potter said.

Marthe has received dozens of awards and medals from international organizations and countries including Israel, Vietnam and France. In 2014, Germany awarded Cohn its highest award, the Cross of the Order of the Merit. The German Consulate General Los Angeles issued a statement that Cohn was “honored for her courageous missions as a French spy who risked her life behind German enemy lines to bring an end to WW II and defeat the Nazi regime.”

“I was amazed that they gave an award to someone who was a combatant from a country that was against them,” said Cohn, who has twice met the president of Germany, Frank-Walter Steinmeier. For her 100th birthday on April 13, 2000. Marthe received a congratulatory phone call and a letter from him thanking her for her “tireless work and efforts to keep the memory of the Shoah (Holocaust) alive.”

Cohn, the mother of adult children Stephan and Remi, does not think that serving in the French secret intelligence was her biggest challenge. “Raising children is the hardest thing I know in life because you never know if you are right or wrong. As a spy, I knew it was the right thing to do,” Cohn said.

Since the unveiling of her secret life, Cohn has delivered over 1000 talks around the world. She likes to speak to young people because “they have such short memories.” Major carries a bag of her medals to these presentations.

“He’s now her wingman,” Potter said.

During her talks in Germany and in interviews with German media, audience members and even broadcasters have apologized to Marthe. She reassures them that they are “not responsible for what their grandparents did.”

On forgiving the Nazis who killed her fiancé and 30 of her relatives in the Holocaust, Cohn said, “I can forgive them for what they did to me, but I absolutely cannot forgive them for what they did to other people. I have no right to do that.”

“Marthe has a great message of hope to people. She basically says that you have to stand up for what you believe is right, and I think she’s done that all her life,” Potter said.

“I think about the war when I’m alone and I daydream. I think constantly of it. It comes completely alive in my brain,” said Cohn, who never took notes or kept a journal.

“You have to know the past, so you know how to prepare for the future. I feel it is my mission to remind people that one person can change things — if they want to do it.” PEN