Real and replica at the Getty Villa

Digital reconstruction of the Villa dei Papiri: view of the terracing of the Villa from the south. Courtesy of Museo Archeologico Virtuale di Ercolano

Originals meet the replicas in the Getty Villa’s “Buried by Vesuvius”

Few of us will have the experience of digging a well in our backyard which leads to the unearthing of an entire seaside estate. But that’s sort of what happened in 1750 when well diggers were stopped by an exquisite marble floor. What if they’d been ten feet off? Would the Villa dei Papiri still be asleep deep underground?

Mosaic floor with complex meander in room o, Roman, first century BC, in situ. © Archivio dell’arte – Pedicini Photographers

We would have scant or certainly scantier knowledge about Herculaneum if J. Paul Getty hadn’t become intrigued with the accounts of its beachfront villa and then (based on Karl Weber’s plan; see below) decided to build a replica of it to house his growing collection of Greek and Roman antiquities.

If you could go back in time and mention “Villa dei Papiri” to the inhabitants of the site, they’d scratch their heads and look at you funny. For all we know, they might have called their residence “the Getty Villa,” if they’d called it anything at all. We call it what we call it today only because of the discovery of papyrus scrolls, found there in 1752. We’ll return to them in a moment.

The villa was built around 40 BC by Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, a Fox Searchlight Pictures studio executive, or at least the Roman aristocratic equivalent of one, presumably, but also the father-in-law of Julius Caesar. Money and prestige, in other words. His son, Piso Pontifex, seems to have been a power broker as well. You certainly don’t end up with 90 marble and bronze sculptures and a coastal retreat by working at the local Walmart. But their loss has been our gain.

Athena Promachos (First in Battle), Roman, first century BC-first century AD; marble. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples. Image: Giorgio Albano

It also served as something of a getaway from the pressing concerns of urban life, a sanctuary of sorts where one could indulge the senses as well as the mind. For example, as Hallett notes, the “sculptural furnishings gave the Villa the air of a blessed place, inhabited by gods. The luxurious materials, the running water, the trees and other plantings, all combined to produce a distinctive blend of sensory delights for the owner and his guests. But the presence of so many divinities and mythical beings elevated these pleasures into a lively celebration of the blessings of the natural world.”

It’s also the best preserved site of the late Roman republic.

This brings us to the library, which didn’t contain books (Gutenberg having yet to be born) but rather tightly wrapped scrolls. The estimate today is 1,100, but also categorized as 1,837 fragments. Fragments of books? Here’s why:

When found, they weren’t simply sitting on shelves, waiting to be taken down, the dust blown off and then read. Instead, they were carbonized to the point where initially they were thought to be charred logs, ancient bolts of cloth, or even fishing nets. Some were probably discarded or used as torches, until one was dropped, broke open, and letters could be seen. Early attempts to unravel them often ended in their utter destruction. Eventually there was some success with the creation of a papyrus unrolling machine devised by Father Antonio Piaggio around 1756. To say it was laboriously slow is an understatement. As noted by German antiquarian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, “In four or five hours of work, no more than a finger’s breadth at most can be lined and loosened, and it takes an entire month to complete a full palm’s width.” In short, grass grows faster.

Three carbonized scrolls, Greco-Roman, second century BC-first century AD; papyrus, wood, and volcanic material. Biblioteca Nazionale “Vittorio Emanuele III,” Naples. Image: Su concessione del Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali

Poet (“Pseudo Seneca”), Roman, first century BC-first century AD; bronze, bone, and stone. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples. Image: Luigi Spina

There are several bronze busts of Epicurus and his cohorts on display discovered in or near the library.

On the subject of libraries, Athena (or Minerva) was the goddess of Wisdom, and she was also the patroness of libraries. A marble sculpture of her was unearthed along with the others. And, as Hallett sees it, this full-scale Athena “is undoubtedly the most important work of sculpture at the Villa.”

I won’t argue with that assessment, but some may say she now has strong competition since the discovery and excavation in 1997of a slightly larger-than-life Peplophoros (a scholarly way of saying “a woman wearing a peplos,” which looks somewhat like a negligee). But she’s probably something more than a housekeeper or nanny, and likely to be a depiction of Hera or Demeter.

Woman Wearing a Peplos (“Demeter” or “Hera”), Roman, first century AD; marble with pigment. Found in the seaside pavilion, April 21, 1997. Parco Archeologico di Ercolano. Image: Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali – Parco di Ercolano

On the other side of the coin is “Pan and a She-Goat,” portrayed in flagrante delicto, so to speak, which is exquisitely carved but at the same time brings up the question (and not for the first time): How does subject matter influence our acceptance or rejection of art? Works like this often don’t survive the centuries, in particular the prudish ones.

Easier on the eyes is a small sculpture of a prancing piglet, which has more significance when mulled over than it does at first glance. Think back to your high school years, during that first week or two of summer vacation when you didn’t have a care in the world. The moral is this: We are piglets today, pork tomorrow. Carpe diem, etc., etc. The work is placed near a portable sundial in the shape of a ham or prosciutto. Sort of like an early Roman version of a wristwatch.

Pan and a She-Goat, Roman, first century AD; marble (from Carrara) and pigment. Found in the southeastern part of the rectangular peristyle, March 1, 1752. Photo by Jon Wyszpolski

For a further elaboration in that vein one should study the garden statuary, including such works as the “Drunken Satyr.” This piece is one of the many that stands (or reclines) replicated in the Getty Villa’s Outer Peristyle Garden. These many works, artfully placed, encourage the visitor, now as it did then, to stroll about leisurely, to relax and to unwind or to ponder and philosophize. And the cool thing is, if I haven’t alluded to it already, is that this is the only exhibit of this kind where the visitor can see the ancient originals on display and then step outdoors to experience a life-like recreation of their original setting. Here, in “Buried by Vesuvius,” we not only can relish specific, detailed information about a unique private residence destroyed/preserved nearly two centuries ago, we can also imbibe a sense of place to go along with it. Allowing for various liberties and inexact details, of course.

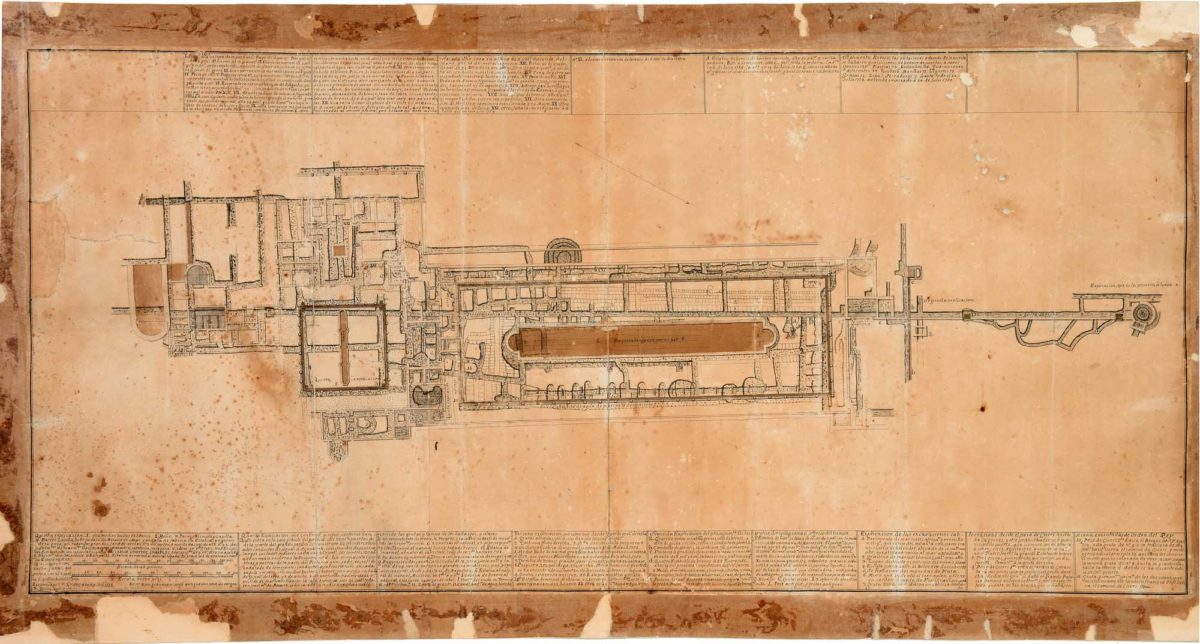

Excavation plan of the Villa dei Papiri, 1754-58, by Karl Weber; vellum, ink, gouache, and pencil. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples. Image: Giorgio Albano

Tripod components, Roman, first century BC-first century AD; ash wood and ivory. Found in the seaside pavilion, 2007. Parco Archeologico di Ercolano. Image: Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali – Parco Archeologico di Ercolano. © Archivio dell’arte – Pedicini Photographers

Before we go, mention should be made of Kenneth Lapatin, curator of antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum, for shepherding this exhibition through all the mazes and around all the hurdles that major shows inevitably encounter. If you were able to catch “Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection” (2012) or “Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World” (2015), then you know that his contributions have been invaluable on so many different levels.

So try not to miss this one. Chances are you’ll never see anything quite like it again.

Buried by Vesuvius: The Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum is on view through Oct. 28 at the Getty Villa, 17985 Pacific Coast Hwy, Pacific Palisades. Hours, Wednesday through Monday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Closed Tuesdays. Free, but reservations required. Parking, $15. The exhibition catalogue, although not an easy one to breeze through, contains numerous essays by scholars and specialists in their field. Like the show itself, it’ll take you back to a remarkable moment in history. (310) 440-7300 or visit getty.edu. ER