Redondo demands nearly half a million dollars after Hermosa Beach backs out of water project

The south end of the Greenbelt in Hermosa Beach. The city rejected a previous proposal to build a subterranean project in the area to address stormwater, citing concerns from nearby residents, but is still searching for a way to address runoff. Photo (CivicCouch.com)

Hermosa Beach is facing demands from neighboring Redondo Beach to turn over more than $400,000 related to a multi-city ocean water quality project, potentially imperiling cooperation on a critical environmental issue.

In a letter sent last Wednesday to Hermosa Mayor Stacey Armato, Redondo Mayor Bill Brand demanded that Hermosa return $431,615.05 Redondo contributed to a beach cities effort to address water quality impacts associated with the flow of stormwater runoff into the Pacific Ocean in front of the Redondo Beach Chart House.

Hermosa had previously offered to return about three-fourths of the money, and to do so only after certain changes had been made in project administration; Redondo’s letter sternly rejects this possibility, and implies that it is considering litigation against Hermosa.

“We cannot imagine what justification Hermosa Beach could have for refusing to return those funds immediately,” Brand wrote.

Hermosa staff and elected officials declined interviews on Brand’s letter. In a statement, Armato said the city was evaluating Redondo’s letter internally.

“We continue to be optimistic about working collaboratively with our city partners to accomplish our stormwater goals,” she said.

The letter marks the latest setback for Hermosa in its attempt to address stormwater runoff from county and municipal drains into the ocean. The issue is vexing cities throughout Southern California. Los Angeles County officials estimate that cities in the region may be on the hook for as much as $20 billion to resolve stormwater issues over the next two decades, and in 2016 voters passed Measure W, a countywide parcel tax to fund stormwater projects. Redondo’s letter, however, suggests other kinds of financial consequences. Along with the demand for repayment, mounting delays in projects meant to improve water quality could expose Hermosa to millions of dollars in fines and legal settlements.

Under the federal Clean Water Act, cities are obligated to address “pollution” flowing to the ocean, including runoff passing through their storm drains. In 2013 Hermosa and Redondo, along with Manhattan Beach, Torrance, and the Los Angeles County Flood Control District, received approval to form the Beach Cities Enhanced Watershed Management Program (EWMP), a collaborative effort to construct local and regional projects to meet their environmental goals.

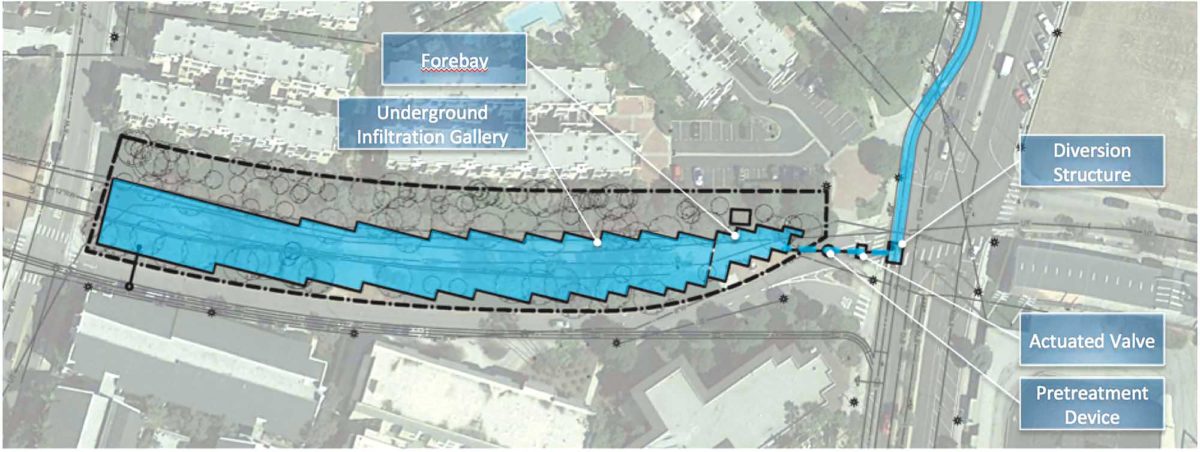

The money Redondo is seeking was intended to go toward an “infiltration project” underneath the Hermosa Beach Greenbelt between Second and Herondo Streets, which was to be one of the EWMP’s primary “regional” efforts, addressing pollution from each of the member cities. Under draft designs, it would have a capacity to divert as much as 319,000 cubic feet of stormwater from the Herondo storm drain through a series of tanks and filtration systems. Over a 72-hour period, that water would be steadily infiltrated back into the underground aquifers, instead of heading for the Pacific.

The Herondo storm drain is one of the largest in the region, and the stretch of ocean surrounding its outfall, on the border between Hermosa and Redondo, has historically had some of the worst post-rain water quality in the southern Santa Monica Bay. It received an “F” during year-round wet weather in Heal the Bay’s most recent Beach Report Card.

Poor water quality can gravely sicken swimmers and surfers, and stormwater flow is estimated to cost the region tens of millions of dollars every year in forfeited recreational opportunities and healthcare costs.

Previous Hermosa councils took various votes advancing the Greenbelt project into pre-design phases, but it attracted little notice until an on-site meeting in spring of 2018 and a subsequent Easy Reader story. Residents complained of being caught off guard by the project, and worried about quality-of-life impacts during and after construction. Over the ensuing year, city officials held multiple special meetings and offered a number of solutions to try to assuage their concerns. But they ultimately became convinced that the Greenbelt site, as well as an alternative location underneath South Park, were simply not suited to a project as big as the one called for by the EWMP.

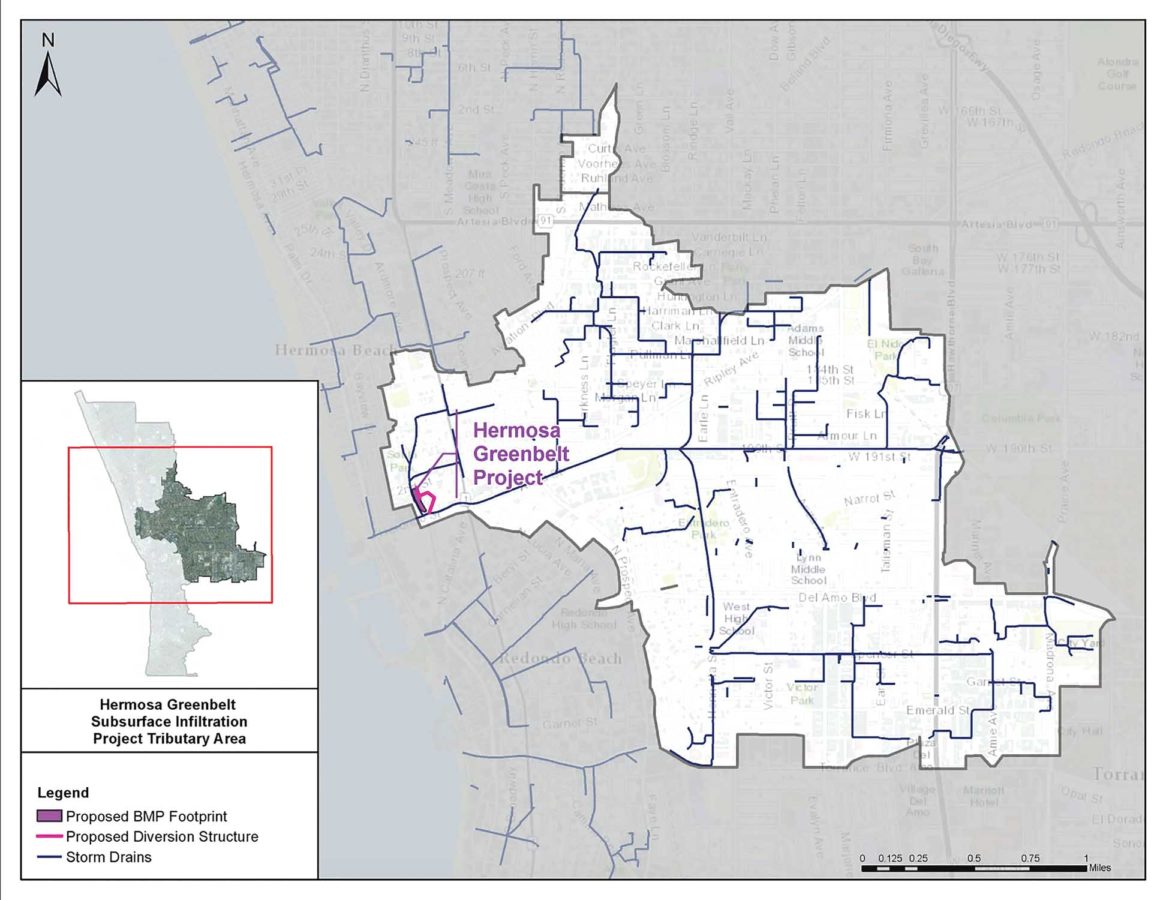

A map of the area feeding into the Herondo Street Stormdrain. Image courtesy City of Hermosa Beach

“The recommendation we made was based specifically on going out to properties, standing on the front doors of properties on the Greenbelt, and going to South Park, spending hours at South Park over the weekend,” said Hermosa Councilmember Hany Fangary at a March 26 council meeting. At that meeting, the council voted to abandon the Greenbelt project in favor of alternative ideas to address stormwater goals, focusing on locating a project over the border in Redondo.

Uncertainty over Redondo’s willingness to go along was apparent from the beginning. Hermosa Councilmember Justin Massey, who appeared divided on the dais over his vote, expressed concern about the plan, but said he was willing to give it a shot.

“I sure wish we had a binding commitment from Redondo Beach. I’m willing to trust your judgment that Option 3 is viable and support it,” Massey said, addressing Armato and Fangary and their proposal to shift the project out of Hermosa.

Moving the project out of Hermosa and designing a new one in Redondo would require amending the Memorandum of Understanding among the EWMP’s members that governed the implementation of regional projects. Each of the member cities would have to agree to the amendments.

Three weeks after the vote, Massey and Armato appeared before Manhattan’s City Council, asking them to agree to the modifications. Stephanie Katsouleas, Manhattan’s Public Works Director, urged the council to hold off, noting that there was “a little bit of a chicken and egg situation” between Hermosa and Redondo about financing necessary studies for alternative projects. And before the vote, then Mayor Steve Napolitano asked whether Redondo was on board.

“We don’t know yet,” Massey told the Manhattan council. “The mayor has been in contact with Mayor Brand, and staff has had extensive discussions, but it has not been brought to the Redondo Beach City Council.”

Manhattan’s council nonetheless voted unanimously to approve the modifications, but both Torrance and Redondo declined to do so. Several weeks later, the State Water Resources Control Board Announced that it was pulling more than $3 million in grant funding that had been awarded to the beach cities to deal with stormwater. Hermosa’s City Manager Suja Lowenthal said that the state board chose to pull the grant because changing the project’s location had added “a lot of uncertainty about the project scope, the project outcomes and project benefits.”

This prompted a new tactic from Hermosa: dissolve the MOU, and start anew. In a June 7 letter — the one to which Brand’s letter from last week was responding — Armato said that a new start could provide “an opportunity to reimagine our collective approach to capturing and cleaning the stormwater runoff in this watershed.”

This lofty goal, however, may remain hampered by the decision to abandon the Greenbelt project.

Along with its demand for repayment, Brand’s letter recent letter laments the “waste” of design expenses associated with the Greenbelt proposal. At the time of Hermosa’s vote, $123,190.74 of the $431,615.05 Redondo had contributed to the design of the Greenbelt project had been spent already; in a June 7 letter, Hermosa offered to return the unexpended portion, $308,424.31, after all of the cities in the watershed group had agreed to dissolve the agreement that governed the project. Redondo is demanding immediate repayment of all of its Greenbelt project money, in part because it was “unilaterally rejected by Hermosa Beach based on the public pressure rather than design or other substantive concerns.”

This accusation is likely to irk opponents of the Greenbelt project, who have gone out of their way to insist that they are not motivated by NIMBY-ism, and to express their support for the underlying environmental goals of the project. But the lingering effects of the localized opposition have altered Hermosa’s approach to stormwater in ways that may make it harder or more costly for the region to meet Clean Water Act Requirements.

For much of the year in between the on-site meeting that first drew attention to the Greenbelt project and Hermosa’s vote to pursue alternatives, Hermosa officials did not concede that there was anything wrong with the Greenbelt site. In a June 2018 study session on the project, the city arranged for several presentations that attempted to explain the highly technical process by which the EWMP arrived at the Greenbelt location. Kathleen McGowan, a consultant on the project, explained that scientists and engineers had examined sites throughout the watershed that feeds into the Herondo Drain, and determined that the Greenbelt site was best suited to handle the runoff. Its location near the end of the drain, the relative absorption rate of the soil underneath, and the fact that the land was publicly owned all contributed to the choice.

One thing that was not considered was proximity to residents.

“No, and that obviously was an oversight,” McGowan said. Groans rumbled through the packed council chambers. “You think?” one man shouted sarcastically.

According to Hermosa staff, more than 700 residential units are within 500 feet of the Greenbelt site. But for infiltration projects, not considering the number of people living nearby appears to be more a feature than a bug. Twelve plans covering watersheds throughout the southland, including that of the beach cities, have been submitted to the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board; none of them use proximity to residents in deciding where to site projects.

This is in part because infiltration projects are presumed to be relatively innocuous. Infiltration projects work by imitating what would otherwise occur were it not for Southern California’s abundance of impermeable pavement, in which water would steadily seep into the ground, instead of reaching the ocean as a deluge. Most of the infrastructure associated with them is buried under ground. State officials have said that it is “fairly rare for there to be significant public objection to buried infrastructure like the Hermosa Beach Greenbelt Infiltration Project.”

“Impacts to the community would likely be quite minimal after the temporary impacts from construction,” said George Kostyrko, director of the office communications for the state water board.

This idea was heavily disputed by residents of The Moorings, a collection of townhomes abutting the south end of the Greenbelt, and others living nearby. They pointed out that almost all other infiltration projects in the region — and all of the ones that were as large as the one proposed for the Greenbelt — were located in parks or other large open spaces, with more distance between the edge of the project and the nearest homes. And these residents also stressed what they said were long-term risks posed by an infiltration project, including subsidence and soil liquefaction.

“Frankly, every time it rained this winter, I kept thinking that if the infiltration project were in the ground at this time, literally millions of gallons of water would be continually flowing underground within feet of my neighbors’ homes,” Moorings resident Carla McCauley wrote in a March 25 letter to the council. (The Greenbelt project’s forecasted volume of 319,000 cubic feet is equivalent to almost 2.4 million gallons.)

A schematic of a proposal, since rejected, to build a stormwater infiltration project beneath the south end of the Hermosa Greenbelt. Image courtesy City of Hermosa Beach

Administrators of other watershed plans have said that specific site worries, such as the possibility of liquefaction, are typically addressed later, after designs have been finalized. While still considering the project, Hermosa’s council promised it would conduct a full Environmental Impact Report for the Greenbelt project, in addition to the one done for the watershed plan as a whole. And at one community meeting, Massey promised residents that, if an EIR were to reveal a risk of liquefaction or other damage to homes, then the council would never proceed with the Greenbelt project.

But by the time Hermosa’s council chose to pursue a project in Redondo, a different narrative had come to hobble the Greenbelt project: that it was fundamentally unfair for Hermosa to host a regional stormwater project for a watershed to which it contributed a relatively small share of the runoff.

“Let Redondo deal with it. They cause a far larger percentage of the problem than Hermosa does,” wrote resident Kathleen Thomas ahead of a Hermosa council meeting.

Under a formula that accounted for several projects Torrance constructed before the formation of the Beach Cities EWMP, Hermosa was responsible for 13.6 percent of the runoff from the Herondo drain; Redondo is responsible for just over 50 percent.

While design and construction costs have been apportioned based on runoff contribution, the siting of projects has not. In the June letter to Brand, Armato suggested that a revised agreement would include new ways of determining where projects would be built. Some, such as building a greater number of small local projects, to limit the amount that a project located at the foot of the drain would have to handle, have widespread support, and Torrance has said it is looking at further efforts to reduce upstream flow to the Herondo drain.

But the June letter also said that Hermosa would urge “limiting the volume of stormwater any city must capture to 150 percent of its contribution” to the Herondo drain. Such a provision appears to be unique to the beach cities, and represents a notable departure from the regional cooperation that most experts say is important to addressing a problem like stormwater.

Watershed groups have tended to design programs prioritizing regional projects to maximize the ability to treat stormwater, rather than ensuring that each city contain projects representing its fair share. For example, the management plan for the Ballona Creek watershed calls for the largest regional projects to be in Inglewood, Beverly Hills and Culver City, even though the City of Los Angeles makes up the overwhelming majority — more than 80 percent — of the watershed area.

While there are several reasons for this, the main one is price. The Ballona plan, like others in Southern California, states that larger regional projects “located near the downstream ends of large drainage areas” and on public land are typically the most cost-effective way of treating large volumes of stormwater runoff.

If the beach cities are unable to come to an agreement moving forward, it’s possible that they would simply go their separate ways, and deal with the amount of runoff each is responsible for. It is unclear how much it would cost for Hermosa to design and build projects covering only its own contribution to the Herondo drain, but the city could end up spending far more than it would have on the Greenbelt proposal. With the state grant and cost sharing agreement, Hermosa’s total contribution for design and construction costs of the Greenbelt project would have been about $580,000. Costs for Hermosa’s Strand Infiltration Trench, a separate EWMP project with a volume 20 times smaller than the Greenbelt proposal, are estimated at around $500,000.

According to its recent letter, Redondo will decide whether to agree to dissolve the MOU by late August. This is the first step in what Hermosa is seeking, but it would hardly be the end of its troubles.

The EWMP is the reason that the beach cities are not currently facing fines under the Clean Water Act. Improvements in the Santa Monica Bay were technically due years ago, but with the formation of the EWMP, the L.A. regional board granted the cities a reprieve while they worked on a joint plan; if the cities were to choose to pursue goals individually, this immunity could be in jeopardy.

Even if it holds, under the EWMP, the beach cities now face a compliance deadline of July 2021 to plan, permit, design and construct projects needed to address stormwater pollution, a deadline they appear increasingly unlikely to meet. After that point, Clean Water Act penalties for exceeding the wet weather thresholds can reach $37,000 per day. If fees were to be imposed on each of the beach cities, City Attorney Michael Jenkins has also said that the other cities in the EWMP could conceivably sue Hermosa, arguing that its failure to move forward with the agreed-upon Greenbelt project caused their inability to meet pollution targets.

An extension of the July 2021 deadline would have to be granted by the L.A. regional board. In previous interviews, officials there have said that extensions may be granted for “good cause.” An official with the regional board said Tuesday that she had not seen the recent letters between Hermosa and Manhattan until an Easy Reader reporter provided them, and declined to comment on how a provision limiting the siting of projects to reflect a city’s contribution to a storm drain would affect the board’s likelihood to approve amendments or grant an extension.