The Huntington turns 100: She’s grand, she’s beautiful, she’s lively

“Nineteen Nineteen” installation view. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

“1919” – The Huntington kicks off its centennial celebration

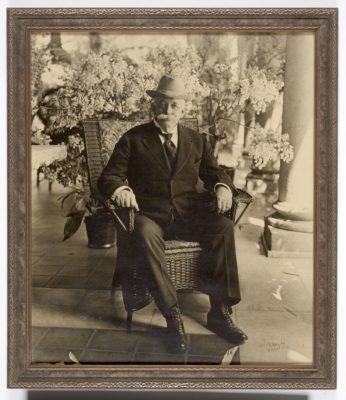

George R. Watson, Portrait of Henry E. Huntington on Loggia of San Marino Residence, April 1919; printed 1927. Gelatin silver print, 22 x 18 3/4 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Organized by James Glisson, the Interim Chief Curator of American Art, and Jennifer Watts, the longtime Curator of Photography and Visual Culture, “Nineteen Nineteen” highlights about 275 objects (and not just artworks) that “were made, published, edited, exhibited, or acquired in 1919,” all of them drawn from the immense holdings of the Huntington collection, of which there are some 11 million items.

In that sense, it’s a narrowly-focused and yet a wide-angled look back, and at the same time by implication an exhibition that’s casting a long shadow on the century ahead. On that note, there is a slight name change, from the formal Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens to the still-formal Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Of course, simply say “the Huntington” and everyone knows what you mean.

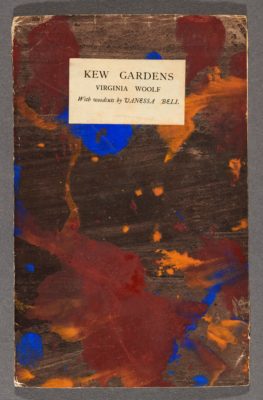

Virginia Woolf (1882–1941), Kew Gardens, 1919. Richmond, England: Hogarth Press. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Henry Huntington (1850-1927) was the nephew of Collis Huntington, one of four partners who created the Central Pacific Railroad. Henry went to work for his uncle at an early age and eventually owned the Electric Pacific Railway, which put streetcars (the fabled Red Cars) and streetcar lines throughout Los Angeles. Rather sadly, as we know, the automobile industry put an end to that and in the process deprived Los Angeles of its early public transportation system.

At any rate, Henry Huntington made a lot of money and seems to have been the J. Paul Getty or the Eli Broad of his day. With his art, his gardens, and his library we have a stellar example of what is best in Mankind. Whether or not Huntington had an unsavory side, I don’t know, although he was against unionization and his Mexican employees were paid less than their European American counterparts. Which, a century ago, may not have been so unusual.

What should be noted is that Huntington saw opportunity and he acted upon it. The catalogue for the exhibition makes this clear: “As the twentieth century began, Henry Huntington bought up great swaths of Southern California land and laid mile after mile of track in every direction… From 1900 to 1919 the population of Los Angeles County increased by an astounding 450 percent.”

Howard Chandler Christy (1873–1952),The Spirit of America—Join, 1919. Lithograph, Boston: Forbes for the American Red Cross, 40 x 25 3/4 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Today, do wealthy men still acquire, or aspire to acquire, large libraries? Furthermore, do any of them do so while at the same time building an impressive art collection and overseeing expansive, elaborate gardens?

For that matter, what would Huntington think of the estate’s Chinese Garden, which will open eight new acres next spring? Last summer’s site-specific theatrical presentation, “Nightwalk in the Chinese Garden,” surely enthralled everyone lucky enough to see it, and one hopes is a harbinger of more such events to come (to accompany the opening, an exhibition entitled “A Garden of Words: The Calligraphy of Liu Fang Yuan” will be on view in the new Studio for Lodging the Mind, currently under construction).

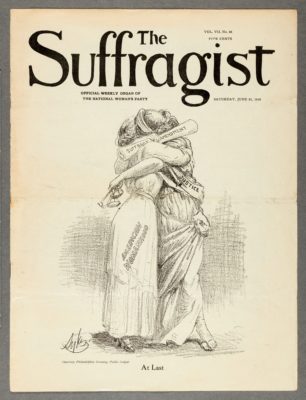

Charles H. Sykes (1882-1942), At Last, in The Suffragist, June 21, 1919. National Woman’s Party, Washington, D.C. 13 1/2 x 10 1/4 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

“Nineteen Nineteen” contains more information than thrills, if I can put it in such terms, and if one misses the show it’s all there, and then some, in the handsome catalogue, which sells for $40. It’s very much a little time capsule between hardcovers, which will also serve as an introduction to Henry and Arabella Huntington. What they left behind for us is a treasure, and it only seems to become more attractive as the years go by. Here’s to another 100!

The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens is located at 1151 Oxford Road, San Marino (take E. California Blvd. past Caltech to S. Allen Ave. and turn right). Hours, Wednesday through Monday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. “Nineteen Nineteen” is on view in the MaryLou and George Boone Gallery through Jan. 20. Call (626) 405-2100 or go to huntington.org. ER