“The Unmaking of a College” – Revolution in action [MOVIE REVIEW]

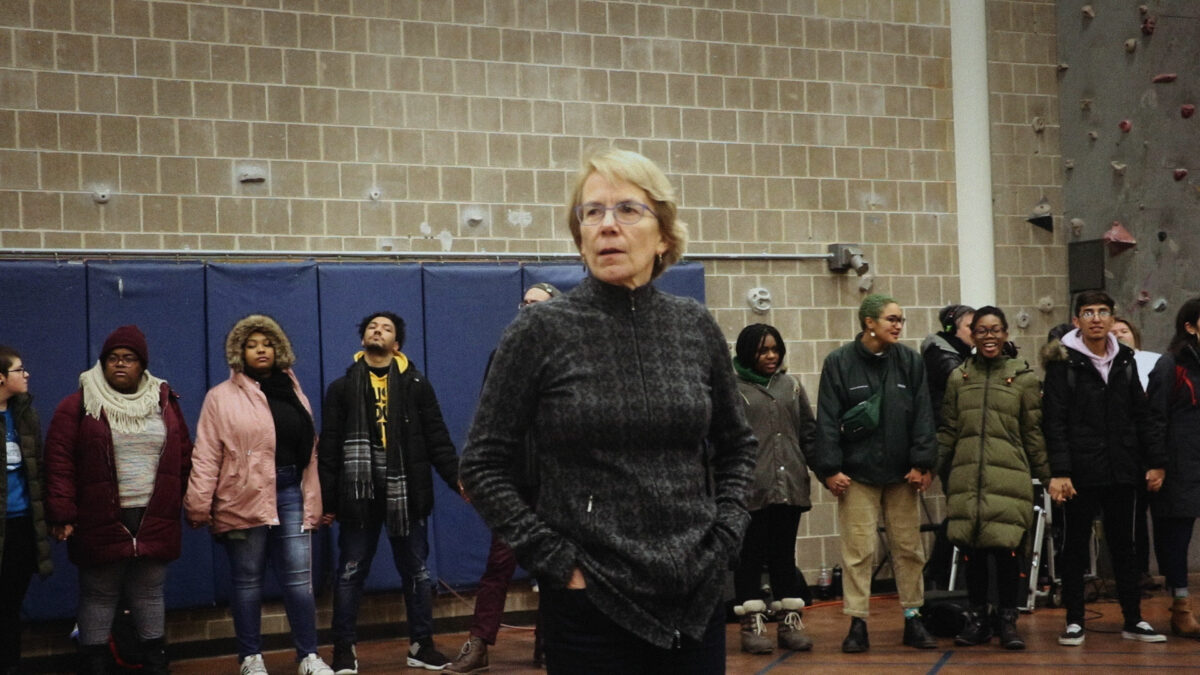

President Miriam “Mim” Nelson in “Unmaking of a College.” Photo courtesy of Span Productions.

In 1966 Franklin Patterson, a professor at Tufts, wrote The Making of a College: A New Departure in Higher Education, in what amounted to be a manifesto on liberal arts education. He saw what it was, but more importantly what it could do and proposed a redesign that was put into practice at a new college where, in 1970, he became its first president —Hampshire College.

In his own words, he proposed:

To reconstruct liberal education so that young men and women may find acceptable meaning in social order and acceptable order in the freedom of an increasingly subjective culture.

To put the private college in a strong cooperative relationship with other institutions.

To reorient the college as a corporate citizen, active in the civic problems and processes of its surrounding community.

His college would “seek to be an agent of change” as well as a laboratory for finding ways to make it “a more effective intellectual and moral force in a changing culture.”

The consortium of collaborative schools, all located in Amherst, MA, where admission to one gave access to the others were Amherst College, Smith College, Mt. Holyoke College, UMass Amherst, and Hampshire College.

Hampshire stressed independent study and educationally it has been a success where even so-called “weird kids” could find a community. Financially, not so much.

In 2018 the counter-revolution arrived with the seventh president, Miriam “Mim” Nelson, formerly a professor of nutritional science at Tufts University, an author of several popular books on women’s health, and, in a fitting bit of irony, the spitting image of Betsy Devos. Within four months of arrival she held a town hall, during winter break, to announce that Hampshire College was in danger of closing, that there would be no incoming freshman class for the next academic year, and that the only possible way out was a “strategic partnership” with another institution. No discussion, no input from faculty or students at this historically egalitarian school, no fundraising outreach, no transparency. Close or partner up. She had only recently come to the idea of a strategic partner and that their consortium colleague was the logical choice. The proposed partner? UMass Amherst, a big public institution with a recent history of swallowing a small college (Mount Ida College) for the value of its Boston real estate, closing the school and dismissing the student body and faculty after the scholastic year ended.

Shocking the students and faculty alike, Nelson further announced that the Board would be taking a vote on her proposal within the next few weeks. Why a public institution whose curriculum was the antithesis of what Hampshire represented? Pleading with the President and the Board members present, the students asked merely that the vote on Nelson’s proposal be put off until the Hampshire College community was given time to address the issue and possible alternatives. No. Not possible.

Students strategizing in “The Unmaking of a College.” Photo courtesy of Span Productions.

Reeling from the revelation and wounded by Nelson’s approach and the impact that closing the school would have, the students rallied. They would stage a “sit-in” unless the Board and Nelson agreed to put off the vote until all options were discussed. Hampshire has a long history of peaceful protest and the students thought this would be the way to go. What, at the beginning, was a hodgepodge gathering of undergrads became a highly organized, skilled group of committed students determined to be heard. When the Board and the President continued to stonewall the protesters and held a vote confirming the Nelson’s proposal, the students went into high gear, refusing to leave the President’s office and the administration where, in organized groups, they set up schedules, bedding, food runs, and a system of volunteers so that the students could continue to attend classes while others “manned the fort,” preventing the administration from conducting business as usual.

Soon the major media outlets picked up on the story and the student revolt. Discoveries, in the form of secret emails revealing a timeline that ran counter to Nelson’s statements, were made that embarrassed the administration, Nelson in particular. Her statement that she had recently decided upon UMass as a strategic partner was a lie. Almost from the moment she arrived, she had been in negotiations with them, making major concessions on how the merger should look and how UMass, having suffered major public relations blowback on their purchase of Mount Ida College, should be portrayed as a white knight in this takeover, while at the same time pulling all the strings about how it would occur. They were, effectively, backing Nelson into a corner from which she was finding it hard to maneuver.

As new revelations emerged, the students, backed up by local Hampshire alums, held their ground. Hampshire has undergone financial problems in the past, as have many small private colleges, but fundraising efforts have always pulled them away from the brink. Their endowment is miniscule compared to powerhouses like Yale and Harvard, but Hampshire was only 49 at the time, unlike the more established colleges and universities who have been in existence more than a hundred and sometimes 200 years. It takes time to build up a deep-pocketed alumni base. Dismissing the fundraising and development departments at the school, as Nelson did as a counterintuitive measure, eliminated an important avenue of possible rescue.

Cheyenne Palacio-McCarthy in “The Unmaking of a College.” Photo courtesy of Span Productions.

Other alumni weigh in on the crisis. Ken Burns, class of 1975, talks extensively about the value of his Hampshire education and what made it unique. He emphasized that the school’s motto, “To know is not enough,” shaped him in everything he did from the moment he started there.

Director Amy Goldstein, Hampshire class of 1980, has produced an extraordinarily watchable, thriller of a documentary. She not only puts a laser beam on the actions of President Nelson but also focusses on many of the student leaders who articulate their belief in the college and what it meant to them, especially those viewed as outside the mainstream either because of gender or sexual orientation or their need to study differently because of learning disabilities. What they all shared was an appreciation for the unique individual approaches that were embraced at the school. Goldstein makes you understand what was at stake for these students and the faculty interviewed on screen. As the crisis unspools on film, you have a front row seat and should be cheering at the end. I wish I had had that level of commitment when I was in college. With her own team of cinematographers she gets up close and personal. Aided by student Marlon Becerra as a story consultant, historical background augments the incisive interviews of most of the key players. Certainly this is a type of guerrilla filmmaking with a stated point of view, but the criticisms are in the realm of what isn’t said as opposed to what is. We never learn why Nelson, with scant administrative experience, was chosen and by whom. Was she aware of the financial crisis she would be facing? Who was her inner circle? And who approved her scorched earth policies before she presented them because even college presidents don’t act in isolation especially when it comes to what amounts to the academic equivalent of Chapter 11 or worse, Chapter 7 in bankruptcy. To paraphrase the famous Hamilton lyric, we want to know who was in the room where it happened.

Opening Friday February 18 at the Laemmle Monica Film Center and the Laemmle Pasadena Playhouse 7.