Tripping over health: The Blue Zones Project’s plan to re-engineer communities, one city at a time

Ali Steward, Beach Cities Health District’s director of Youth Services, cleans up a school garden during BCHD’s Volunteer Day. BCHD’s health priorities have evolved over time, from Blue Zones programs to custom plans as community needs have shifted. Photo by David

A broad smile flashed across Dan Buettner’s face when he took the stage at Sherwood Hall in Salinas, California on June 26. His presentations, by this point, are well-oiled — he’s gotten good at rolling into a city and offering a plan for their residents to turn around their health.

“You’re the 50th community we’ve come into,” Buettner says. “That means we’ve made all of the mistakes in 49 other communities. This time, we’ll be perfect.”

Buettner’s a tall man with an athletic build, a bright smile and a gift for turning a phrase — think Harold Hill of “The Music Man,” with a bicycle instead of 76 trombones. But he’s done his damnedest to set himself apart from the usual cadre of talk-show, quick-fix health gurus.

Since the 2009 publication of “The Blue Zones: 9 Lessons for Living Longer From the People Who’ve Lived the Longest,” Buettner has devoted himself to the reengineering of communities so residents are tripping over health.

But unlike Hill, he plans to stick around the communities he blows into.

“People are stubborn. We forget stuff, we’re barraged with information and ideas, and…even the best diets only last for about seven months, because people lose focus,” Buettner said in an interview. “You’re never going to change America by trying to convince America to change its habits.”

What works, he’s found, isn’t changing the human — it’s changing everything around the human.

Take, for instance, Ventura Boulevard, the stretch of road outside of a Studio City cafe where Buettner sat last February. It’s a five-lane corridor for traffic between the 101 and 405 freeways. If Buettner had his way, he’d reduce the number of traffic lanes, establish four-foot buffered bike lanes, and slow traffic down from 45 miles per hour into the low 30s. The road would become one where humans could actually see the other humans around them, rather than their shiny metal shells.

“What are the chances that a car going by right now is going to see a store and say oh, that’s right — I need to pick up wine for tonight?” Buettner asked. “When you slow traffic down, business does better, it’s safer, the air is cleaner. When people become more locally-focused, they’re less likely to have this stranger anger…if you shape your environment, it’ll shape you.”

Communities where Buettner’s Blue Zones Project have taken root have benefited. He points to case studies in outposts like Albert Lea, Minn., to work combating food deserts in Texas, and to surveys showing that, while most regions of the United States have felt greater despair over the past three years, Blue Zones communities have largely held steady.

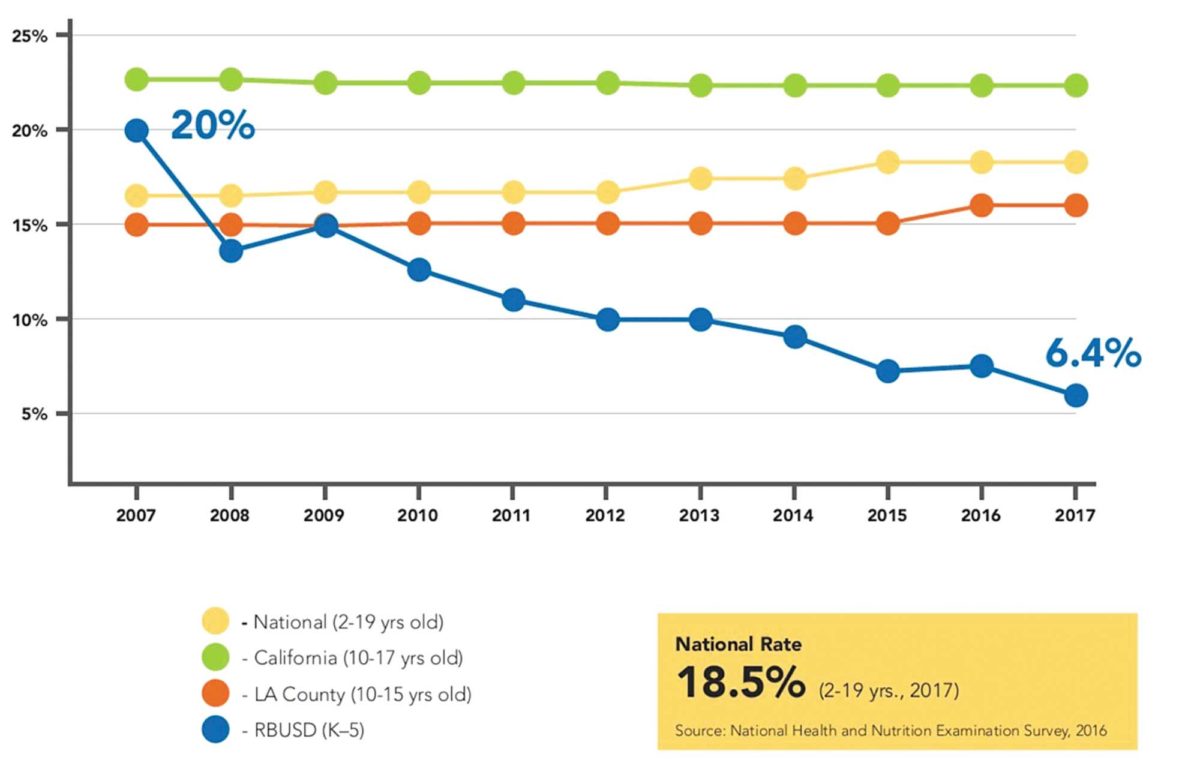

The Beach Cities Blue Zones Project touts one eye-popping stat: the childhood obesity rate in Redondo Beach’s elementary-aged students has plummeted over 10 years, from more than 20 percent down to 6.4 percent.

The key to Blue Zones success hasn’t come from any one thing; the strictures of the project are broad, covering “people, places and policy,” Buettner said.

But what seems most important is that Blue Zones communities have an infrastructure, a framework, and a sponsor in place to advance the cause before the Blue Zones Project launches.

“The challenge is finding communities that are ready for it,” Buettner said. “Communities that are willing to invest the political equity.”

Without that, there’s no point.

“We’ve had about 420 cities apply, and worked with about 45 cities,” an acceptance rate of about 10 percent, Buettner said. “Step one is readiness. Step two, there’s a funder. This work doesn’t happen by itself; it happens with trained people, working a plan for five to 10 years.”

The Blue Zones Project was born more than 15 years ago, when Buettner, a renowned adventurer and journalist, led a five-year study, built on the shoulders of existing demographer research, to five communities: Nicoya, Costa Rica; Ikaria, Greece; Loma Linda, Calif.; Okinawa, Japan; and Sardinia, Italy. His mission was to determine the commonalities causing those areas to have more centenarians, per capita, than anywhere else in the world.

His reporting eventually became a book that packaged those commonalities into a set of nine principles (the marketing-friendly “Power 9”) for people to live longer, better lives. The people in those often-rural communities make physical activity a part of their everyday activities, rather three hour-long sessions at the gym each week; their diets are plant-based, focused on fruits, vegetables and legumes, but generally include some meat; and they’re well-connected to the people in their communities.

The book was a hit, spawning four follow-ups to date. Buettner became a familiar face on daytime television — but he had a nagging feeling in the pit of his stomach.

“I’d sit in the green room after spending five years doing deep research, and I knew what I found — then I’d see one fad scientist, one fad diet-writer after another in the green room with me,” Buettner said. “I wanted to prove that this would work.”

In 2009, he got his chance. A $1 million grant from AARP gave him 10 months to prove his idea: Change the environment of a community (in this case, Albert Lea, Minn.) and you can dramatically change lives.

He proved his point.

Reports from 3,600 Albert Lea residents, participating in what was then known as “Vitality City,” showed they lost an average of 2.6 pounds and, and that health care claims for city employees dropped by 49 percent.

Buettner’s organization was courted by Healthways (later acquired by Sharecare), a private company specializing in establishing “well-being” plans for corporate personnel, and the pair forged a partnership. In 2010, they put out a call asking for communities to pitch them on why they should become their next Blue Zone outpost.

The Beach Cities Health District answered the call, and the Beach Cities was chosen from a group of 55 cities from across the country.

“From my perspective — focusing on health behavior — I saw it as a tremendous opportunity for a collective impact model, engaging sectors across the Beach Cities,” said Lisa Santora, then BCHD’s Chief Medical Officer.

The Beach Cities were an ideal pick for the first Blue Zones Project. The three cities provide a large, densely populated area, in the country’s second-largest media market. The community’s bid was further buoyed by having the Health District as the backbone organization.

“We benefited from the fact that, as an organization, we had staff with a public health background who had the knowledge and know-how to work alongside Healthways,” Santora said.

Healthways got their model community — one both primed with a healthful culture, and hungry to continue improving. And BCHD was able to continue on its path toward improving community wellness through preventive health measures, which became its mission after it shut South Bay Hospital and steered away from acute care more than a decade earlier.

But the Beach Cities had another ace in their pocket, in the form of easy-going CEO Susan Burden.

Burden’s background is public health, but her roots are midwestern. She’s a Missouri farm girl, with a kind aspect and a relaxing smile. “But don’t mistake her for this sweet little thing. She’s pushy, she’s crafty, and I love it,” said Redondo Beach Unified School District Superintendent Steven Keller. She’s not a pitbull in negotiations, but a golden retriever, making her tugs of war so enjoyable that opponents didn’t realize she’d won until they saw her walking away with all the prizes.

BCHD received $3.8 million in cash and in-kind services from Blue Zones Project while only paying $1.5 million over three years — and in its first amendment to the deal, BCHD effectively won the right to license Blue Zones Project imagery, so long as they adhered to Blue Zones Project tenets.

The business arrangement has worked out for both the Health District, which has used the brand while putting its own spin on the Blue Zones Project playbook, and for Blue Zones, which has used BCHD as a test-lab and welcome wagon for newly-established Blue Zones Projects.

But what the Health District really sought was a way to determine the health needs of its residents through as much data as they could manage to dig up. That approach came from CEO Burden’s leadership — she sought to bring an evidence-based approach to public health. Blue Zones gave BCHD that path.

The Well Being Index was created as a collaboration between polling giant Gallup and Healthways (later Sharecare) to provide “an in-depth, nearly real-time view of Americans’ well-being,” in five areas, according to Gallup. A problem with most health metrics and data sets is that, often by the time they’re released, they’re out of date.

“The downside to the national data is that it generally lags two or three years behind,” said Erika Graves of Sharecare. “There’s a time-lag, where we’re collecting more real-time data and don’t have a national comparison for the same time-frame.” Similar problems linger for localized datasets — UCLA’s AskCHIS tool uses data from the California Health Interview Survey, but only on county-wide or region-wide bases. The newest neighborhood-level data from CHIS is, at this point, three years old, collected in 2016.

WBI, in partnership with Blue Zones, promises to bring near-immediate data to member communities through Gallup’s continuous polling with telephone and mail surveys to broad regions. Pollsters take a representative oversample of Blue Zones communities in particular — such as the Beach Cities — allowing locals to drill down into what their residents need and want.

What the WBI has found in the Beach Cities is that the community is largely thriving compared to the rest of the country: residents have increasingly reported good physical health, less smoking, and better healthy habits, like increased physical activity and more healthful eating.

They’ve also reported that they’re stressed, unclear about their life’s purpose, and often feel disconnected to people within their communities. In 2011, the WBI found that more Beach Cities residents, by percentage, were feeling stressed than residents of post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans. Reporting has improved since then, but not by much: 43.4 percent of residents say they deal with “significant” daily stress, higher than the national average.

In response, BCHD has shifted its community health priorities away from changing the built environment (as when it helped steer Redondo Beach to the construction of a protected bicycle path alongside the city’s waterfront, connecting Redondo to the rest of the Strand, and advocated for anti-smoking policies across the three cities) and toward re-enforcing social and emotional well-being.

“One interesting thing to me about this whole model…if you’re successful with Blue Zones Project, it becomes integrated into the culture of whatever community it’s in,” said Lauren Nakano, BCHD’s Blue Zones project director. “I think it’s a really interesting dilemma, because you have this product that you pay for, but the more it becomes part of a community, the less delineated it is as Blue Zones.”

Nakano points to the Walking School Bus program — a Blue Zones-prescribed plan — that transformed into BCHD’s family-focused Walking Wednesdays, which doesn’t require registration, volunteers, or a limited walking route. Blue Zones-prescribed “Wine @ 5” outings have become Social Hours, monthly get-togethers that steer away from the idea of a group-drinking outing (20.1 percent of Beach Cities adults report having seven or more drinks a week, nearly 8 percent greater than the national average) toward one focused on good food and good friends.

Social programs have evolved as well, as the district leads workshops seeking to reduce stress among children, teens and adults, all who admit to stress and worry in greater numbers than state and national averages.

“As an organization, we have been very responsive to how we continue to adapt to meet the needs of people in our community,” Nakano said. “I think with any agency, it’s our responsibility to listen, to understand, to assess what our constituents need and then respond to it.”

The changes to Beach Cities programming, Buettner said, are great — but not Blue Zones.

“It’s worthy, but if I had my druthers, it’d be on optimizing the environment, rather than behavioral changes,” Buettner said. “But on that side, we continue to point to the Beach Cites successes as a point of pride for us.”

Body Mass Index measurements indicate far lower rates of childhood obesity among Redondo Beach’s elementary-age youth than across the county, state and nation. Image courtesy BCHD.

Klamath Falls

Klamath Falls, Oregon hasn’t historically been known as a bastion of health. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s annual County Health Rankings examine and rank each county within each state by their health factors and health outcomes. Since 2010, Klamath County has been at or near the bottom of RWJF’s rankings for both morbidity (quality of life) and mortality (length of life).

In 2013, two women decided to change that. “No one wants to be last,” said Katherine Pope.

Pope and Stephanie Van Dyke met as classmates at Johns Hopkins University, as they pursued graduate degrees in public health. The two were both well-versed in traditional medicine — Pope is a registered nurse; Van Dyke was trained as a primary care physician. But both felt they weren’t doing enough.

“I was working in oncology and bone marrow transplants, working in a hospital in Phoenix. I loved my job, but you could spend upwards of a million dollars on a single patient…I felt like I could do more,” Pope said. She was helping five people per day, but she wanted to help more people in a lasting way — to effect deep change within a community, rather than fixing them temporarily.

When the two graduated, they cemented their medical partnership by moving to Klamath Falls and finding employment at Sky Lakes Medical Center, where Van Dyke undertook her medical internship. Together, they developed the Sky Lakes Wellness Center, with a mission statement to teach the community to live healthier lives by demonstrating disease prevention and reversal, establishing community policies and changes to the built-environment.

The Wellness Center began using data from Sky Lakes — the only hospital within 10,000 square miles — and examined health risk factors: smoking, type-2 diabetes, high blood pressure and obesity, among others. They also began looking into walkability and alternate, non-vehicular, modes of transportation, and began mapping out the unhealthiest, most at-risk neighborhoods, with the help of the nearby Oregon Institute of Technology.

As they worked, the Wellness Center sought out grant funding. But just as they missed out on one opportunity, they learned of another: the Blue Zones Project sought to establish itself within Oregon with a bang, at what was called the Oregon Healthiest State Kickoff, at an event in Portland, clear on the other side of the state.

Klamath would not be denied. About 30 members of the community drove about 278 miles, in a snowstorm, wearing matching T-shirts: blue, with gold letters naming the town of Klamath Falls in a baseball jersey-like cursive. An image of a pelican — the symbolic bird of Klamath — completed the design.

“We made a splash,” Pope said. “Everyone knew who Klamath was at the end of the Oregon Healthiest State conference.”

The coalition made a broad-ranging pitch: They peeled back the layers of their community health rankings, discussed what chronic diseases are doing to their community and discussed the economic costs Klamath was suffering, and then looked at the benefits that other communities (including the Beach Cities) were reaping. The pitch ultimately became one of community pride — to reiterate how much Klamath Falls could do to make itself better.

The pitch stuck, largely due to the passionate people of Klamath Falls, like Dr. Glenn Gailis.

For more than 40 years, Gailis tried to make the biggest difference he could in his community’s health. “But I think I failed miserably,” Gailis said, taking it personally that the community’s diabetes, obesity and heart disease risk factors rose during his active years practicing medicine.

For years, he’d watch as his patients would shrug off one treatment suggestion after another; watch as he’d send them to a specialist, hoping that would scare them straight, only to come back with a $300 medication. Drugs and medications could be valuable treatments, he acknowledged, but not necessarily solutions to issues of high blood pressure or cholesterol or even diabetes — that can be achieved through weight-loss caused by lifestyle change.

After his 2014 retirement, he happened to meet Van Dyke in a chance encounter, and had nothing but praise for the vision of community wellness she espoused. His research into the Blue Zones Project had him convinced that Blue Zones was a community effort that could actually make a difference, even in communities like Klamath that aren’t wealthy. He was among the group that went to Portland to pitch Klamath to Blue Zones, and has remained an ardent supporter, even coming out of retirement to work with the Wellness Center.

“I think our hospital CEO and our board is committed to saying that we can do a better job than this — that we can’t do crisis sick care all the time, that we have to do wellness efforts,” Gailis said.

The local Blue Zones Project is spearheaded by Healthy Klamath, a public-private collaborative effort that acts as a clearinghouse for data, repository for events and momentum-builder for policy change. (Surprisingly, according to Executive Director Merritt Driscoll, Healthy Klamath is an informal handshake deal between the Core Four organizations: Sky Lakes, Klamath County, Cascade Health Alliance and Klamath Open Door). The project, she said, had its bumps along the road, especially within the first year: Blue Zones restaurant partners that had embraced the project changed their menus, dropping their healthy options; grocery stores dropped their signage and stickers without replacing them. The community had the energy — they just needed to be continuously engaged.

It’s been the job of Jessie Hecocta, Healthy Klamath’s relationship manager, to keep engagement moving, not just among restaurants and businesses, but among schools. Klamath is working to get students into healthy eating habits young, in elementary and middle school, before they get to high school and travel off-campus for unhealthy lunches. As a member of the Klamath Native American tribes, Hecocta has also been involved with outreach among tribe-owned businesses — but they’ve had to fight skepticism. There have been small successes, she said, as Healthy Klamath has worked to get into convenience stores (a strategy for introducing healthful foods that’s a proven winner in food deserts in Texas) but breaking through into casinos and hotels has been a challenge in some cases. Not to mention, tribal lands are far-flung and spread away from Klamath Falls proper, where Healthy Klamath’s influence is strongest felt.

“I’m a tribal member myself, but it’s still difficult to be able to get your foot in the door with individual members and organizations,” Hecocta said.

According to Driscoll, the biggest areas of opportunity for Klamath include greater outreach to its lower-income populations, and its Hispanic community. “We’ve tried to put out materials in Spanish,” as well as other “culturally-appropriate materials,” she said, “but we could do a better job of that.”

One point of pride has been attempts to derail food insecurity through an online, year-round market, Klamath Farmers Online Marketplace, where residents can buy meat, honey and seasonal produce year-round. Klamath has also passed tobacco-free city parks and tobacco licensing ordinances, and has developed a protected bike lane.

“I think if we had more money going into our park system and our recreation district, then our community would be thriving more,” Driscoll said. “But we’re fortunate here…although we’re an economically disadvantaged community, we have supporters that are helping us thrive. Klamath Falls is making its name nationally.”

County Commissioner Kelly Minty Morris feels that, despite the challenges and opportunities Klamath is still facing, the community has been wildly successful.

“We went from an area that had some struggles on the health front, certainly…while it hasn’t been long enough yet for our project to make a dramatic swing, all of the momentum is pushing in the right direction.”

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation agreed, naming the community a 2018 Culture of Health Prize winner for the strides its made in the past years.

“The data will catch up, and it will reflect positive changes,” Morris said. “It may take longer than I’d like, but it’s undoubtedly been positive and successful.”

Stephanie Van Dyke died in 2017, killed in a sledding accident, and the community lost one of its truest champions. “She was a dynamo — when we lost her, talk about getting the rug pulled out,” Gailis said. “She was just a bundle of energy, and so is Katherine. They really were instrumental in pushing this through and saying ‘we want to do this, even if you don’t come here.’”

Early this summer, the $750,000 Klamath Commons park project opened, Van Dyke’s long-time dream. The ribbon cutting ceremony featured hundreds of attendees — including Pope, who earlier this year moved to her home state of Indiana with her husband — and according to the local Herald and News, there were few dry eyes at the event.

Van Dyke’s fingerprints can be found all over the park, especially at the gazebo in its heart, which displays a quote from the late doctor:

“Rather than assuming time will change the wrongs of the world, in reality, we have to change them ourselves.”

BCHD CEO Tom Bakaly shovels soil during BCHD’s Volunteer Day. As a former city manager, he said that “quality of life” used to mean road and traffic problems. Now, the shift is toward resident well-being. Photo

Salinas and beyond

The Central Valley community of Salinas, California’s salad bowl, is still within the first six months of its Blue Zones kickoff, and though leaders are excited by what’s coming and what’s been done, the groundwork had been laid many months before Buettner’s speech in June.

“We did a big announcement in January, then went quiet purposefully,” said Blue Zones Project Monterey County Executive Director Tiffany DiTullio. The project was like a duck in a lake, peaceful above the water, but churning like mad under the surface.

“What we’ve found is, when you bring a new project like this to Salinas, there’s some resistance early on from groups that feely they’ve been doing that work,” DiTullio said.

Salinas has already been the center of numerous health- and community-improvement projects, including the California Endowment’s Building Healthy Communities effort and the Alisal Vibrancy Plan, which focuses on improving the quality of life in East Salinas as part of the city’s General Plan update.

An ongoing project has sought to increase connectivity among the community, not just in Alisal or Old Town Salinas.

But the biggest challenge is the community is diabetes — 57 percent of adults in Monterey County are diabetic or pre-diabetic.

“We’re making sure we’re aligning our work out there, working with schools, worksites and restaurants” as well as faith-based organizations, non-profits and schools, DiTullio said. The challenge, she said, is tying together the work of disparate organizations, all of which are fighting the same battle on different fronts.

They’ve found some victories with worksites, and challenges in others — policy and progress don’t always match, and some organizations with wellness initiatives have had fairly low compliance, finding fewer than one of five people participating.

“Policy takes a long time. You really have to make sure people understand the why, then it’s easier to accept and adopt it,” DiTullio said.

One thing stood out from that June kickoff weekend though: While Buettner’s English language talk packed Sherwood Hall’s auditorium, a second, Spanish-language presentation was sparsely attended.

DiTullio acknowledged that as a challenge and an area of opportunity. “In most cases, it’s much easier to go to them than for them to come to us,” she said. “But we’ve created relationships through the schools and family resource centers, and we’re utilizing those.”

The project has a total of four years and eight months to build those relationships as it self-evaluates — the length of the contract established between Blue Zones and its partners in the Monterey County venture: Salinas Valley Memorial Health System, Taylor Farms and Montage Health.

The organizations were reticent to discuss terms, but a representative for SVMHS — a public health district — stated that it was paying a total of $12.3 million over the length of the contract, or about $2.6 million annually. That figure, according to a SVMHS staffer, does not include costs fronted by its partners at Taylor or Montage.

That’s well above what both BCHD and Klamath Falls list as their current costs. Healthy Klamath’s website states that Sky Lakes Medical Center funds $200,000 annually, as part of a 2-to-1 funding match with Cambia Health Foundation. BCHD, in its licensing agreement, pays approximately $110,000 per year — but that’s with the freedom to use the Blue Zones brand without directly working with Blue Zones staff.

“The Beach Cities should consider itself lucky — it’s the only community we’ll ever license the brand to again when we’re not directly working there,” Buettner said.

As the founder of the project, Buettner acknowledges that, to a certain degree, he has to relinquish control to the communities — like the relationship between an architect and a contractor.

“Not every single aspect of it works, but we carefully design the program so there’s no downside. Putting in more sidewalks isn’t going to hurt anybody. Making more farmers markets isn’t going to hurt anybody,” Buettner said. “Does it always work? No. But I deploy 80 interventions in a city, 30 of them fail and 50 of them work? I’m going to hit the ball out of the park.”

His biggest concern, at every turn, is the project’s quality — which is why he let slip that he’s working on a “Blue Zones 2.0,” an ongoing evolution of the project with a “rockstar team…relentlessly driving for innovation and improvement,” he said.

(For their part, BCHD acknowledged that they’ve discussed ongoing Blue Zones projects with Buettner. But when asked directly about Blue Zones 2.0, officials declined to expound further.)

“The most important thing is shifting the focus away from the delusion that we’re going to change individual lives of a population one-by-one with behavior modifications, and shifting to architecting behaviors by shaping the environment,” Buettner said.

As he said that, Buettner was more than 1,000 miles away from the Beach Cities, at the site of a new Blue Zones project in Montana — and as he spoke, headed toward his next meeting, he rolled along on his bicycle, preparing to woo the next group of people with a plan to change their towns and their lives.

David Mendez’s reporting on the Blue Zones Project was undertaken as a USC Center for Health Journalism 2019 California Fellow.