Turning darkness to light: Blind entertainer, author, athlete, altruist Tom Sullivan conquers a sighted world

by Robb Fulcher

Tom Sullivan has lived a limitless and star-studded life in his 76 years and counting.

As an entertainer, he’s appeared on Johnny Carson’s iconic late-night TV show dozens of times, acted his way to two Emmy nominations on prime time shows, cut records for major labels, and

sung the National Anthem at a Super Bowl.

As a writer, he’s produced successful TV scripts and 15 books, including one that was made into a major motion picture.

As an athlete, he became an excellent golfer, a snow skier, a triathlete and a Hall of Fame AAU wrestler.

On the altruistic front, he and his wife Patty have raised more than $10 million on behalf of blind children, as he uses his good name to promote their cause and to deflate societal stereotypes.

He is so sought after as a corporate speaker that he’s done more than 3,000 such gigs.

Almost as a side note, he has been blind from birth. Yes, a side note. Sullivan has lived such an unconfined life, “turning darkness to light” at every turn, that the fact of his blindness in a sighted world seems an afterthought.

“I’ve had the most eclectic life,” he understated in an interview. “My life has come in chapters, and it’s been all about finding purpose. How can I be valuable enough to be significant in the lives of others.

“Every one of us has a disability. Some disabilities are subtle. The question is, what do we do with them? How can you turn a disadvantage into an advantage?”

Tom Sullivan with Betty White, who introduced Sullivan to his future wife Patti.

Climbing fences

Sullivan was born three months premature, and lost his sight when his incubator was over-oxygenated, destroying his retinas.

It was 1947. A doctor advised his parents to place Tom in an institution, where he would be safe. They tried so hard to keep Tom safe that he had to reach beyond their protection from an early age.

“My parents sent me to the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston, and I hated it. Early on I wanted to be in the world outside the gates of that school.

“I learned a lot, and I’m grateful for that, but that school was a prison,” he said.

On weekends home from the boarding school, young Tom found himself in a well-intended prison of sorts, in a home with a backyard surrounded by an eight-foot high chain link fence.

“My parents were trying to protect me, but they were keeping me inside and the world outside.”

By age 8, he would spend time listening to other children’s games that were carried to his ears from the outside world.

“There was a Little League baseball field down the street, and I would hear the sound of the bat hitting a ball, the ball hitting a glove. I wanted to be in the game, but I couldn’t.

“I had a portable radio, and a Louisville Slugger my dad had given me. l would listen to the Red Sox, throw rocks up into the air, and hit them with that bat.

“That was my baseball game. I spent much of my life, at that point, in fantasy. When I threw those rocks into the air, I was Ted Williams.”

Then the Hannon family, with sons Billy and Mike, moved into a newly built house next door.

“I knew that somehow I had to get to them,” Sullivan said. “I remember it as if it was, well, now. It was May 15, 1957. I grabbed that chain link fence in my hands, and I pulled myself up hand over hand, hand over hand, and when I got to the top I just leaped into space – I didn’t know how far it really was – and I crashed to the ground.

“Billy – who has been my best friend for almost 70 years now – said ‘Wow, that was a gnarly fall,’ in this Boston accent. He said ‘My name’s Billy.’ I said ‘My name’s Tom, and I’m blind.’ He said ‘Wow.’

“Then he said three of the most impactful words I’ve ever heard: ‘Want to play?’

“That boy changed my life. He taught me to throw a baseball, wrestle, throw a football. I went to all his games. And I started to feel like I could compete in the world.

“I said wait a minute, being blind isn’t that bad. I can play the game of life.”

The game kept expanding. Sullivan went on to attend Providence College and Harvard University, living in the dorms. On the athletic front, he became a triathlete, a golfer, a snow skier, an AAU wrestler and inductee into the Wrestling Hall of Fame in Stillwater, Oklahoma.

In later years, Sullivan would tell a corporate audience about a turning point in wrestling that provided an enduring life lesson.

“Wrestling is a contact sport. You grab the other person, you throw them on the ground, and you try to kill him,” he said with a smile.

“I lost the first 16 matches in 2 minutes and 43 seconds all together. It was an ugly thing. The referee would blow the whistle, and it would be ‘now let’s beat up the blind person.’

“Before my 17th match the coach, a sarcastic guy, said ‘Do the best job you can, and try not to be dead.’ I lost, but I learned that all I have to do is the best job possible, and if you do that, wonderful things start to happen.

“I won my next 187 matches in a row, went to the US Nationals and the World Championships.”

Piano bars and Betty White

“College life was great for me,” Sullivan said in the interview. “By then I had come to terms with being Tom. I could sing and play piano at parties, and I had no shortage of feminine company.”

Then, when he was 21, Tom met Patty. That is, he was pushed into a chair next to Patty by a matchmaking Betty White. Yes, that Betty White, the beloved actress and animal lover.

“I was singing and playing piano in a bar on Cape Cod, making money to go back to Harvard, and Patty was working in a restaurant across the street.

“Betty White and her husband Allen Ludden [of ‘Password’ fame] were in a summer-stock production, and they would come in every night after the play. Sometimes they would sing, and I would accompany them.

“At that time I was chasing every girl in the joint. And the wonderful Betty White said ‘Tom, you’re an idiot. There’s a girl who comes in every night, alone, and if you could see the look in her eyes when she looks at you, you would never date anyone else.

“Then she brought me over and just pushed me into a chair next to Patty. And that’s why we’ve been married the last 54 years, because of Betty White.”

Tom Sullivan with Betty White, who introduced Sullivan to his future wife Patti. Photos courtesy of Bellows photography

On to stardom

“Betty and Allen were a big part of my entering show business. They brought us out to California, and wound up introducing us to Johnny Carson, Mike Douglas, Dinah Shore, lots of others. That led to me doing a lot of shows, and getting record contracts.”

Sullivan’s showbiz resume is as voluminous as it is impressive. He sang and chatted on The Tonight Show With Johnny Carson, wrote scripts, acted and wrote songs for TV shows including Mork & Mindy, Little House on the Prairie, Highway to Heaven, WKRP in Cincinnati, Touched by an Angel, M*A*S*H and Designing Women.

Along the way, he was nominated for two Emmy Awards.

“The way that all happened, I wanted to work as an actor, but nobody wanted to hire a blind guy. So I wrote scripts and storylines, and I wrote myself into them. If you want the script, you have to hire me.”

On M*A*S*H, Alan Alda’s doctor character is temporarily blinded, and Sullivan’s character helps him expand his consciousness by exposing him more deeply to his other senses.

On Mork & Mindy, Robin Williams’ space alien character learns about blindness.

“Robin had the biggest heart in the world,” Sullivan said of the late comedian. Sullivan told of a time he was shooting a scene with character actor Tom Poston while a pestering director unhelpfully tried to rush the duo. Williams intervened, pulling rank, and saved the situation.

Another time, Mork and Sullivan’s character, exploring the world of their senses, were supposed to ride a tandem bicycle, with Sullivan in the front seat.

“They took us to Griffith Park, and we’re going down a grass hill, and Robin was supposed to tell me which way to go. It turns out he had a bike crash when he was young, and it had traumatized him.”

A rattled Williams was saying “left, left. No, a little more left. Oh God I meant right!”

The laws of physics had their say, the actors and bike landed in a heap, and a director ran up to find everyone on the ground.

“He said ‘Oh [bleep], they broke the bike!’ That’s show business.”

‘Don’t screw it up’

On the musical front, Sullivan sang the National Anthem at Super Bowl X in 1976, using the four and-a-half octaves of his strong, clear, emotive voice to stirring effect.

But just before he went on, while the public address announcer boomed his introduction throughout Miami’s Orange Bowl, Sullivan was subjected to a discordant note. NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle, standing at his side, chose that time to call attention to the size of the TV audience.

“Pete Rozelle turned to me, placed a heavy hand on my shoulder, and said, ‘Boy, there are ninety million people out there, so don’t screw it up,’” Sullivan said.

Despite the commissioner’s artless sendoff, Sullivan stood on the field, in a light suit and wide lapels, and delivered a soaring rendition of the anthem, backed by choir-like vocals from the group Up with People.

Years later, a newspaper survey piece placed Sullivan’s rendition as a favorite, rivalled only by Whitney Houston’s turn in 1991.

A new tune

Sullivan played Vegas for years, and recorded for the Arista and Capitol record labels.

His recording career faded in time, as the pull of family erased any real lure of the road. This occurred in sync with changes in the business.

“What happened is the music changed from the wonderful music of the ‘70s and early ‘80s. Then came disco and heavy metal, and I didn’t fit into either one of those.

“I was still performing in Vegas and Lake Tahoe. I just looked up one day and realized I was out of the formal music business.”

Through TV appearances, including his weekly inspiring segments on Good Morning America, Sullivan was swamped with offers to appear as a corporate speaker.

He said he prepares by connecting with a president or sales executive or the like, to find out who he’s speaking to.

“It’s one thing to tell your story, but it’s another thing to connect your story to their story,” he said. “You have to love your audience.”

Tom Sullivan in a 1987 Episode of “Highway to Heaven,” with Michael Landon, who plays an angel sent to Earth to help people in need. Photo courtesy of Tom Sullivan

On to authorship

In 1975, Sullivan wrote his autobiography, ‘If You Could See What I Hear,’ with co-author Derek Gill, launching Sullivan on yet another leg of his journey.

“That led to me believing I could be a writer, not just of scripts but of books.”

And so he set about writing 15 books at a rate of about one every year and-a-half.

“Some have been best sellers, and some have been real stiffs,” he said.

His literary output includes biographical books, life-lesson books, four novels and three children’s books. In 1982 ‘If You Could See What I Hear’ became a major motion picture.

Sullivan had met Gill when Gill came along to write an article about a near disaster in the Sullivan household that was averted by a “miracle.”

The Sullivans’ daughter Blythe had just turned 4 years old when she nearly drowned in the family swimming pool.

“It never should have happened. Patty went shopping and I was supposed to be looking after the kids,” Sullivan said.

“The phone rang, and it was the first time I was asked to do The Tonight Show. I never even heard Blythe open the sliding glass door. I didn’t hear her footsteps cross to the pool. I heard a splash.”

Sullivan dashed to the pool, dove in and made two laps under the water, groping around in vain for his daughter.

“I didn’t find her. I came up to the surface after the second time, standing in shoulder-high water. I looked up and said ‘God, what kind of joke is this? You’ve given me everything. The girl of my dreams, two beautiful children, now my daughter is dying, and it’s because I’m blind. If you give me this miracle, I promise I will live an exemplary life.’

“Then I heard bubbles coming up to the surface. I found her, brought her up and respirated her.”

The state of the art was chest compressions and blowing into the mouth.

“When I heard her breathe, that was the sweetest moment of my life,” Sullivan said.

Not for profit

Tom and Patty have used celebrity golf tournaments and a legacy foundation to raise millions to aid blind children.

During a segment about the Blind Children’s Center of Los Angeles on Good Morning America, he held a blind baby in his arms.

“I thought back to my own childhood, and how my parents must have felt when they found out they had a blind child. And frankly, from that time on I was hooked, as a fundraiser, as a board member, as an advocate.

“How can I complain when I’m able to use my celebrity for that kind of work,” he said.

Asked how Sullivan’s blindness is beheld by the sighted world, he said, “You learn to assess where people are coming from. If they are patronizing, but mean well, as an adult I learned to accept it.”

He described an irksome type of person who will quiz him, by approaching him and saying “Do you know who I am?” Then they insist that Sullivan guess, if he doesn’t recognize the voice.

“I’m a low 90s golfer, and I’ve had people who can’t break 150 still trying to give me lessons. I have that happen all the time.”

Sullivan made the low 90s with the assistance of a golf coach who helps line up each shot.

“He holds the club in the air like a rifle, in the direction he wants me to hit the ball. I grab the club with both hands, and I position myself. Then he squares up the head, and tells me how far he wants me to hit it.”

Sighted people sometimes underestimate Sullivan, or overestimate him, both of which he can turn in his favor.

“Let’s say I’m negotiating a major contract with a record company or a book publisher. In the first 10 minutes I own it. Whether they underestimate me, or think I leap tall buildings with a single bound, they’re off balance.”

Tom Sullivan with Robin Williams on the set of Mork & Mindy in 1978.

Beyond independence

The sometimes-unenlightened attitudes of sighted people have not dimmed Sullivan’s innate warmth, or turned him jaded.

“I see beauty from the inside out. I’ve never met an ugly person, unless they wanted to be. Unless they saw life ugly,” he said.

While he learned to be fiercely independent, he arrived at a place in life, and his outlook, that is profoundly beyond independence.

“Through my incredible 54-year marriage with Patty, and my incredible relationship with guide dogs, I learned that we are all interdependent,” he said.

Turning to the circumstances of his birth within the medical technology of the 1940s, he said, “If I was born five years later, I probably would be able to see. But as an adult I came to understand that God placed me exactly where I was supposed to be. I turned being blind from a disadvantage to an advantage.”

The Sullivans have lived on the hill since 1973, except for a five-year period when he was hard on the speaking circuit and they moved to Denver, aiming for the middle of the country. Tom Jr. lives on the hill as well, and Blythe in Pebble Beach.

Sullivan loves it here, experiencing the location’s delights with heightened senses.

“I love the game of golf, and walking the golf course. There are so many sensual joys there.

“We used to live on Via Rosa where St. Francis [Episcopal] Church is. My guide dog and I would go down to Redondo Beach to run, in the dark. The dark didn’t bother me. The dog would just take me around the potholes.”

He described 15 distinct ocean wave sounds, from the roar of water over sandbars at low tide, to the rumble of two heavyweight fighters exchanging body blows at high tide.

“There are 11 different textures of sand, if you’re running barefoot. There are over 50 kinds of birds that you hear.”

He described early morning restaurant smells of bacon, eggs and coffee blending with eucalyptus and kelp in a “potpourri of sensual awareness.”

He described sea lions barking from the rocks at Rat Beach, where he would swim in the morning with his beloved guide dog, a golden retriever named Dinah, after longtime friend Dinah Shore.

“She loved the water. We would swim out about 50 yards, and I would float on my back while she swam around me in circles, with the sun coming up.

“Sighted people live in one sense. I have four senses turned way up, so how can I feel cheated? You can’t feel cheated, you can only feel lucky.”

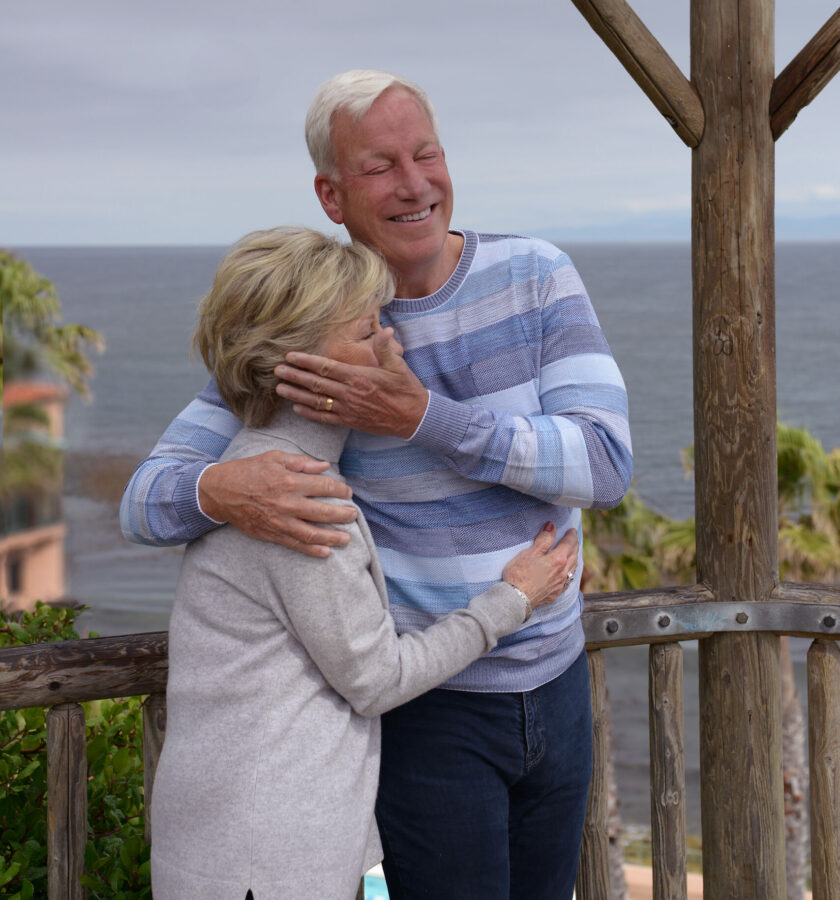

Tom and Patti Sullivan are 50-year residents of the Peninsula. Photo by David Fairchild

Into the future

These days Sullivan is talking up the family’s latest author, Patty, whose book “Betty White’s Pearls of Wisdom” is taking off.

“It looks like it’s going to be a bestseller,” Tom said.

He is still at it as well, working on a historical fiction novel “The Southies,” which should be published next spring.

The story follows three Irish-American friends from South Boston through several decades, as their lives take the disparate shapes of a cardinal in the Catholic Church, a decorated Korean War veteran, and a Whitey Bulger-like crime figure. The friends come back together against the backdrop of the civil rights struggles of the 1970s.

“I’m really having a lot of fun with it,” Sullivan said. “And I think it’s important to really keep my mind active.”

The more one surveys Sullivan’s life, the more his blindness seems like a side note.

“I would love my tombstone to say Tom Sullivan was an entertainer, an author, an activist, a husband and father. And by the way, he was blind,” he said. PEN