Water man: A new biography of Duke Kahanamoku reveals the long shadow he casts on surfing and South Bay culture

Duke Kahanamoku on the beach at Waikiki. Duke shaped many of his own surfboards from trees he cut down. Photo from the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Duke Kahanamoku was not one to suffer from butterflies. Kahanamoku was a native Hawaiian whose ocean-bound childhood enabled him to dominate competitive swimming in the early 20th century. And at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, his first, he nearly missed the finals of the 100-meter freestyle. But Kahanamoku was not psyching himself out in the locker room or fleeing with cold feet; he was taking a nap underneath the bleachers. Rushed to the starting block by his teammates, he captured the gold anyway.

The story exemplifies a kind of stoicism that is now the ideal of surfing. Unwritten rules indicate that one shouldn’t “claim” a good ride, shouldn’t talk excessively in the lineup, and should never speak the name of secret spots. And while brevity may be the soul of wit, it is the bane of biographers. As memories fade and records disappear, how to capture the inner life of the surfing subject?

David Davis’ enjoyable new biography, Waterman: The Life and Times of Duke Kahanamoku, presents a man of many accomplishments and few boasts. The Duke that emerges is a reluctant royal, modestly excited by the extraordinary times through which he moves and presides.

Kahanamoku’s most vulnerable moment in the whole biography comes after he completes his “improbable ride,” a wave that he followed for more than a mile, linking several of the breaks on Oahu’s South Shore. Describing the scene, Davis writes, “Kahanamoku felt a tingle pass through his body, almost as if he was still riding on the board. His heartbeat galloped.”

But there was no exalted hooting, no did-you-see-that gesticulating. (One thinks of current professional surfer and fellow Hawaiian John John Florence, who is known to cap death-defying rides by nonchalantly pushing his hair out of his face.) The wave became the talk of Honolulu, but Duke was reluctant to do much talking himself; he sat silently on the shore, ignoring the gawking and pleading of spectators.

Davis can sympathize. Many of Kahanamoku’s surviving family members and friends spurned interview requests. Though this made his job harder, the author was sympathetic.

“Here’s this haole boy, coming from California, wanting to know all about Duke,” Davis said in an interview. “Maybe it’s natural that they’re not going to reveal state secrets.”

Davis, who will be appearing at pages: a bookstore in Manhattan Beach tonight at 7 p.m. to discuss his book, mined newspapers, letters and archives to find Kahanamoku’s voice and spirit. The result is an exploration of a man who felt most at home in the water, but was inevitably tangled in the terrestrial complications and limitations of his times.

Facing Racism

Kahanamoku’s restraint can be grating, as when Davis is forced to turn to a tame, sterile quotation in situations that ought to churn with emotion. “GIve me a chance and I’ll do my best to make good. I think I can do it,” Kahanamoku is reported to have said before setting out on for his first Olympic trials.

Where does this restraint come from? Some of the plainness of the reported speech in Davis’ book is rightly attributable to Kahanamoku’s reputation as an unshakeable good sport. One imagines that it is also comes from the missionary-driven schooling Kahanamoku received. Like his friend and contemporary Jim Thorpe, Kahanamoku was a pupil in an education system prohibited speaking native tongues, the better to purge the “savagery” from indigenous populations. (Though he never finished high school, Kahanamoku supposedly had excellent penmanship.)

And unfortunately, the careful way in which he revealed himself to the world is bound up in the racism that Kahanamoku, as a native Hawaiian, routinely faced. Davis portrays Kahanamoku as the anti-Jack Johnson, the black boxer who flouted Jim Crow and needled white audiences in the early 20th century. Unlike Johnson, who was perpetually one match away from being lynched, Kahanamoku absorbed the slings and slurs with a “regal acquiescence.” Like Jackie Robinson after him, Kahanamoku had to be not only better but kinder than his competitors.

The provocations he endured are far from trivial. Duke is refused service in a clubs and hotels. When he is not being misidentified as black or American Indian, he is called “Kanaka,” the islander equivalent of the N-word in its time. Davis unearths a cringe-inducing moment during Duke’s journey to the 1912 games in Stockholm. During the long barge ride from New York, Kahanamoku entertains fellow members of the U.S. Olympic team with a performance on the ukulele; they respond by applying blackface and putting on a minstrel show.

Davis finds no raging tantrums from Kahanamoku during any of these incidents, but it would be a mistake to think Kahanamoku was naive. When Kahanamoku sets out for Hollywood in the twenties, he got mostly bit parts, while his Olympic rival Johnny Weismuller stars as Tarzan in six films. Dejected, Duke returned home to Hawaii.

“It’s a crucial time in his life,” Davis said. “But beyond that, I think he also saw that there were limitations, specifically racism.”

At home in the water

As with a good photograph, Duke’s inner life is more apparent in spontaneity than when posed. After surfing at Freshwater Beach near Sydney, Kahanamoku was mobbed by dazzled spectators. Surfing was quite new in Australia, and the scene was all the more incredible because Kahanamoku was surfing quite close to a school of sharks. “Didn’t they bother you?” a lifeguard asked of the experience. “No,” Kahanamoku deadpanned, “and I didn’t bother them.”

The pithy response suggests a man far more relaxed than the observers on the safety of the shore. Even as his celebrity forced him to interact with the world, the ocean was where he felt most at home.

Helicopter parents on South Bay beaches would be aghast at the freedom he had in the ocean as a child. “‘My boys and girls, go out as far as you want,’” was the advice dispensed by Kahanamoku’s mother. “‘Never be afraid in the water.’”

Kahanamoku’s ease saved lives and produced lasting memories. During a large storm near what is now known as the Wedge in Newport Beach, a fishing boat capsized while carrying sixteen passengers. Kahanamoku happened to be on the beach with his surfboard, and he paddled out and back three times to rescue the bulk of the passengers. He was his usual reticent self when reached by a newspaper after the rescue — ”It was done. That is the main thing,” he said — but years later, Kahanamoku was lured onto the set of the TV show This is Your Life, and was reunited with the people he saved. Davis’ recounting of the survivors gratefully describing how Duke saved their lives reads like the closing scene of It’s a Wonderful Life, as a man is finally confronted with how big a difference he has made in the world.

Kahanamoku had friends all over. He was well-travelled in a way that would be difficult in the today’s world. Transferring among slow trains and barges allowed him to stop, and surf, in between. His trip from Hawaii to the 1912 Olympics and back lasted eight meandering months. In between, he surfed in Manhattan Beach and Redondo Beach, and at a famous display in Atlantic City. Even if he was not the first in either location, his celebrity helped draw people to the water in a way that no one had done previously.

“Duke has to be considered a major force in drawing enthusiasm, showing people what can be done,” Davis said.

Arthur Verge, a professor at El Camino College who specializes in the history of surfing, said that while George Freeth may have surfed in the South Bay first, such disputes obscure a broader point.

“There is always a battle of the father of surfing,” Verge said. “I say that surfing doesn’t have a father; it has an ambassador. And that ambassador was Duke Kahanamoku.”

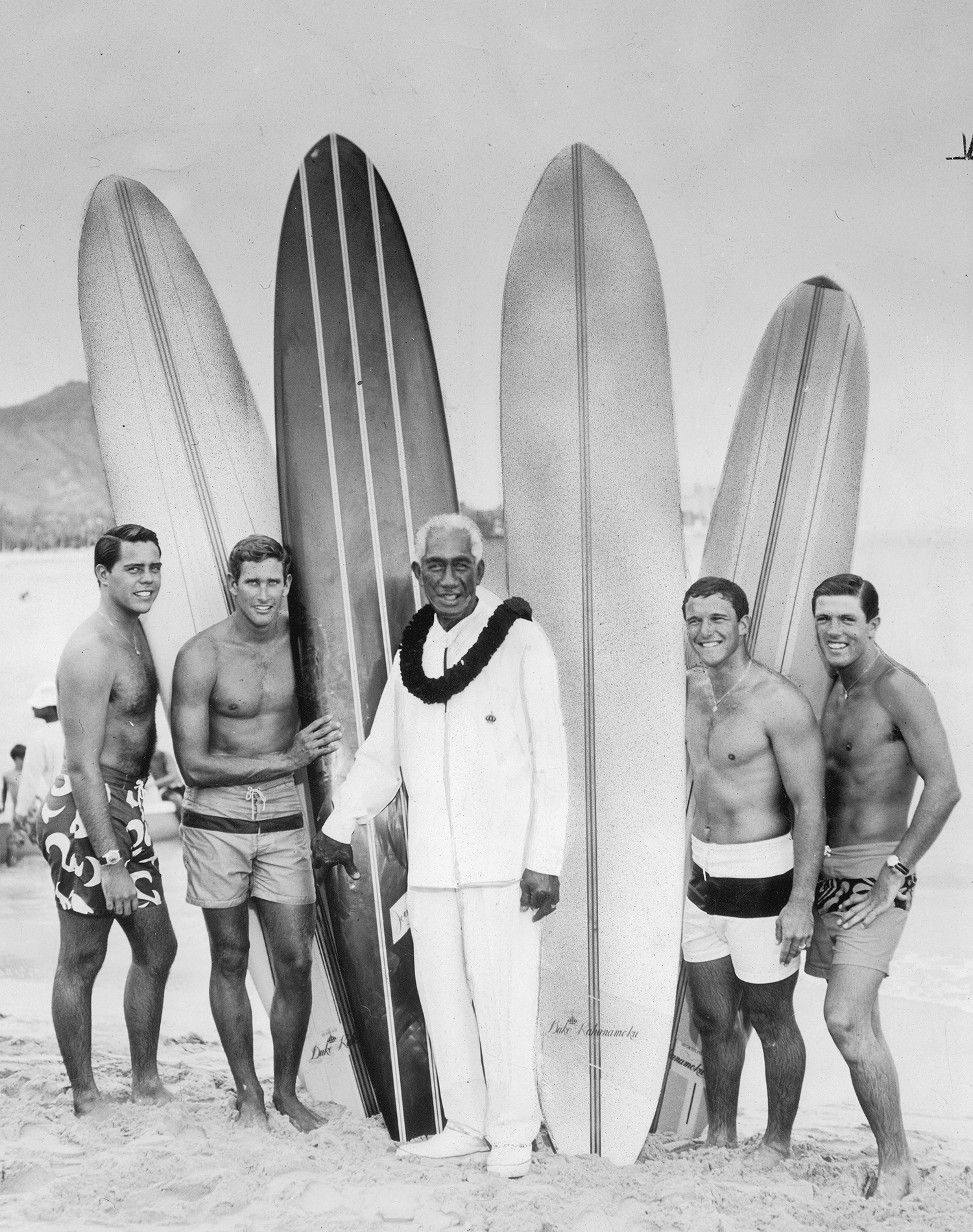

Kahanamoku, center, stands with his all-star surfing team. From left to right: Paul Strauch Jr., inventor of the “cheater five”; Joey Cabell, founder of the Chart House restaurant chain; Fred Hemmings, 1968 world champion; and Butch Van Artsdalen, pioneer of Banzai Pipeline. Photo by Bob Johnson, Los Angeles Herald-Examiner.

The Tao of Duke

Rarest of all were the moments when Duke took time to reflect. “Out of the water, I am nothing,” Kahanamoku would occasionally mutter to himself on returning from the 1920 Olympics, a gold medalist once more. It’s a harsh judgment that becomes more fathomable if one understands that it was not made out of false humility: Despite his accomplishments, Kahanamoku was nearly broke for much of his life. This is true even though, early and throughout his life, powerful interests in Hawaii backed Kahanamoku as a means to promote the islands.

Davis assigns much of the blame to antiquated notions of professionalism in the Olympics. The idea of an all-amateur competition was to keep sports pure, but the distinction is essentially that of allowing hunting for trophies but not for food. People born into poverty, like Kahanamoku and Thorpe, were at a distinct disadvantage. To maintain eligibility for the Olympics, Duke could not earn money from anything related to swimming. Arcanely, this eliminated lifeguarding and coaching.

Kahanamoku took odd jobs for much of his life. Long after winning gold medals, he worked as a janitor and gas station attendant. His celebrity propelled him to multiple terms as Honolulu Sheriff, and he was on the job during the attack at Pearl Harbor.

Even in surfing, the changes earned Duke few rewards in proportion to the changes he wrought, Kahanamoku was born at a time when surfing was not very popular. It had a rich past, but was frowned on by missionaries, who found it that encouraged nudity and distracted from toil. Furthermore, disease had ravaged the native Hawaiian population that held most of the surfing knowledge; at the time Kahanamoku was born, only one-fourth of the islands’ population was Hawaiian or part-Hawaiian. (The numbers are lower still today.) Yet by the time of his death, surfing was a global phenomenon being used to sell everything from beer to time-shares.

As with just about everything else, Davis presents Kahanamoku as a man slow to pass judgment, and temperate when he finally does. Those looking for a bitter condemnation of surfing as a pure thing corrupted by the modern world will be disappointed. About the closest Duke comes is an evaluation of the increasingly packed sand-scape at Waikiki: “It’s good economically, but it sure makes it crowded here.”

Of course, the “crowd” that Duke found at Waikiki is now packing lineups everywhere from Bali to Burnouts. Davis argues that Kahanamoku was the essential link between surfing’s origins in finless redwood and its future in hot-dogging foam. But in doing so, Duke not only turned surfing into a sport — he pushed small coastal towns into the mainstream of American culture. Without Kahanamoku, names like Dale Velzy, Hap Jacops and Dewey Weber would probably never have echoed beyond the confines of the South Bay.

And even as the area changes, attracting residents less interested in surfing or the beach, the legacy remains.

“The genesis is that he brought out the Aloha spirit that people in the South Bay were open to,” Verge said. “Surfing came first.”

Kahanamoku’s athleticism brought him fame, but it was ultimately his attitude that helped the world enjoy the things he loved. As Duke is credited with saying, “The best surfer is the one having the most fun.” ER