Yo ho ho (and a bottle of rum) Reflections on food, culture, the history of rum, and a meal of bananas and beef at 30,000 feet

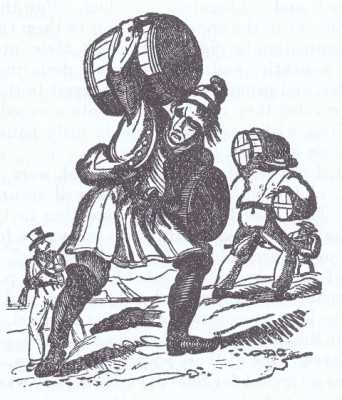

From “The Pirates Own Book: Authentic Narratives Of The Most Celebrated Sea Robbers”, published 1837. The book is full of lurid tales of drunken pirates doing cruel deeds and framed the way people viewed pirates until Stevenson’s Treasure Island came out in 1883.

Writing about restaurants in the South Bay for almost thirty years has given me a sense of food history at ground level, how changes in the local economy and society were mirrored in our dining options. We don’t see this on an everyday basis – nobody does, because only in hindsight can we point and say that here began a trend, there ended a fad, and over yonder was an oddity that was interesting but made no lasting impact. Occasionally something unequivocal would happen, like a famous restaurant burning down, but the most important changes were the hardest to recognize.

My columns for the Easy Reader and twenty or so other newspapers and magazines were surprisingly good training for writing books and articles examining culinary history. I had already been researching food traditions and the origins of arcane spices in order to understand how well local restaurants were executing their food and reflecting their culture. In the process I became aware of the worldwide community of culinary historians, people who study not just recipes and the worldwide movement of food, but the rituals associated with cooking and dining and the way that cultures are shaped by the things they eat.

The author in the midst of his rum investigations. More technically speaking, Mr. Foss is sticking a red-hot poker into a jug of mixed dark beer, rum, eggs, cream, and sugar to make a drink called Landlord May’s Flip that was popular in Colonial America. Photo courtesy Richard Foss

I joined that community and took a journalistic attitude when I wrote articles for the Encyclopedia of World Food Cultures, then a book on the history of rum, a beverage that once was a mainstay of the world economy. It was fascinating to track the social status of rum drinkers as expressed in Colonial American documents, Jane Austen’s books, and the tirades of Prohibitionists, and to make connections between rum and sea chanteys, pirates, and voodoo. Much of what I thought I knew was wrong, and it was delightful to tease out the intricate details of the rum trade. I wasn’t an enthusiastic rum drinker when before starting the book, but I am now – studying and tasting rum for two years changed my mind.

I spent time in libraries and museums, dealing with the unique problems of researching smuggling, tax evasion, and other illicit transactions that by nature are poorly documented. Rum was first made by illiterate people on the fringes of great empires, so nobody knows who had the idea or precisely when. The first conclusive evidence of its invention refers to a trade that was already in process, and the first English language description from Barbados in 1661 calls it “a hot, hellish, and terrible liquor.” Every known reference to it for another fifty years was negative and insulting, because the people in power regarded this beverage, mainly drunk by slaves, sailors, and soldiers, as a nuisance that happened to be lucrative. Rum didn’t move up socially for most of a century, when it became a popular punch ingredient in Colonial America, as well as a cure-all and a trade good with both fellow colonists and the natives. On the negative side, rum distilled in New England also became the foundation of the triangle trade – casks of molasses coming from the Caribbean to be traded for rum that went to Africa to be traded for slaves to the Caribbean to harvest more sugar and make molasses.

As I sought information and images from various sources, I came to appreciate the virtues and limitations of the Web. In some cases, what looked like a scholarly consensus turned out to be endless repetition of the same unsourced stories. Some rum distilleries have cultivated a mystique by using a historic name for a modern company, or claimed ancient distilling traditions in countries that had never had them, and these had to be debunked. There are multiple tales behind the invention of almost every popular cocktail, and sometimes there are bitter arguments – partisans of Don The Beachcomber and Trader Vic can come close to violence over which of those colorful California entrepreneurs invented certain tropical drinks. There was good information to be had on the net, most from online government archives around the world, and I became a fan of the Library of Congress, British Museum, and an Australian site that indexes newspaper articles going back to the 1820’s.

It was an exhausting project, and I anticipated easier going on my next book, a history of food in flight from the zeppelin era to the space station. Certainly records should be easy to find, since the inventors and innovators were all working within the last two centuries. In fact it hasn’t been that easy, since many aircraft manufacturers and airlines have gone bankrupt or merged and their records have been destroyed. The Soviet Union had an airship service rivaling the Zeppelin Company’s endeavors in the 1930’s, but even modern Russian researchers have been unable to pry open state archives. There must be interesting stories about how Aeroflot managed to keep serving food through Siberian winters even during World War Two, but nobody at the company seems inclined to share them.

Some airlines have been very helpful, others surprisingly reticent, and I have wondered if their reluctance to help document recent history might have something to do with the fact that any honest evaluation will be of a steep decline in quality and choice. Fifteen years ago, passengers had over twenty choices of meals, including Hindu, lacto-ovo, or fruitarian vegetarian, and you could almost tailor meals to individual diets. A prankster at a record company who didn’t like the boss ordered different special meals for every flight she booked for him, at one point claiming that the executive only ate raw beef and bananas. Given the level of service at that time, the boss may have actually gotten the most puzzling airline meal ever served. Now choices are fewer than at any time since the 1950’s and the meal costs and quality have been slashed even in first class.

American government agencies and the military have been more forthcoming than airlines; I found some surprisingly funny correspondence about the fact that bomber pilots of the 1940’s were given cans of food to open for inflight meals, but can openers that could not be operated with the gloves they had been ordered to wear. The Boeing company allowed me into their archives in Seattle, and I read the handwritten notes of company executives who flew commercial flights incognito in 1939 and documented every experience, good and bad. These were some of the most sophisticated flyers in the world, and they still broke off their musings about how the service galley might be redesigned to gawk at the Grand Canyon.

That book is about half-finished as I write this article, and in a filing cabinet by my desk are contracts for another book and several encyclopedia entries and scholarly articles. I‘m looking forward to writing those at the same time as I keep writing reviews about restaurants within miles of my home. I love keeping tabs on developments in my own community at the same time as I study food technologies and great global shifts in taste.

Culinary history is integral to culture – we are who we are because of what we eat and drink. It is a fascinating study that extends from our remotest past to speculation and experimentation about our future, as scientists study ancient sites for hints regarding edible plants that could be foods for the more crowded, hotter world that seems to be on the horizon. On a more everyday level, as our separate cultures meld into modern America, documenting the foodways of our ancestors is part of how we keep alive the memory of who they were and how they spent their days. Perhaps someday our contemporary musings, the articles in this newspaper and others, may be cited by scholars of our day. It gives me a warm feeling to think about it.

Richard Foss started writing for the Easy Reader in 1986, and is the author of Rum: A Global History (Reaktion Books). He is also on the Board of the Culinary Historians of Southern California, and teaches and lectures around the country. You can read some articles about rum at his website, rumhistory.com, or richardfoss.com.