Ron and Joan: A love story

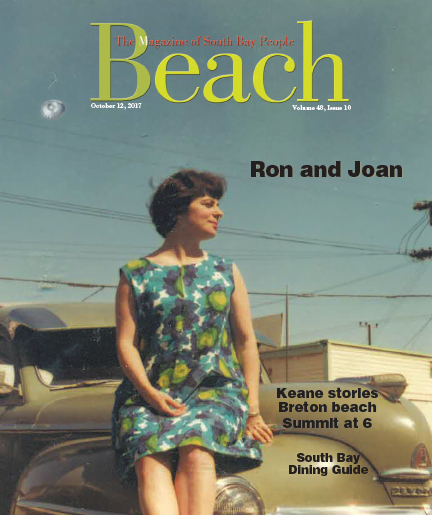

Joan Arias sits atop her and her new husband’s first car, a 1948 Plymouth, a few months after their wedding in 1966. Photo courtesy the Arias family

Early in 1966, at the graduate library in the English Department at UCLA, Ron Arias found himself being dismantled, with playful ease, by a woman he’d just met.

Arias was only 25 but already worldly and a little bit brash. He’d grown up in a military family and attended part of high school in Germany. He hitchhiked around Europe as a 17-year-old, an adventure during which he shared a glass of wine and a conversation with Ernest Hemingway in Pamplona, Spain after the running of the bulls. He’d dropped out of UC Berkeley his junior year to work as a reporter in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and subsequently spent two years in Peru serving in the Peace Corps.

Nothing in all his travels had prepared him for the adventure he was about to embark upon when he first met the gaze of this brown-eyed, fierce young woman who argued circles around him on that day in 1966. The argument was about an obscure poem titled “Fábula de Píramo y Tisbe” by 16th century poet and satirist Luis de Góngora. They argued in Spanish. All the while Ron was trying to place her accent. He thought maybe she was Cuban, or some other Caribbean nationality, both for her quickness of speech and of mind.

“Joan had no problem plucking out the meaning, and I think I was just faking, pretending I knew what I was talking about, when in reality I was being turned on by this very lively, so smart, cute young woman who had a passion for getting at truth,” Ron recalled. “She was fast becoming a spark that was igniting the thinking part of my brain, but in a benevolent way.”

“The women in my family, they all caved in to men. This one did not; she spoke her mind, she was fierce, and yet there was a twinkle in her eye. It was just an argument.”

Her name was Joan Zonderman and she was from Hillside, New Jersey. She’d also just returned to the States; she’d spent a year in Venezuela studying theater as a Fulbright scholar. After their argument in the library, Joan unexpectedly turned up the next day to audit an undergraduate Spanish literature class Ron was taking.

“What are you doing here?” Ron asked her. “You could teach this class.”

Joan smiled. She wasn’t there for the class. They kept looking at each other throughout the lecture. Afterwards, they went on a date. Within days, he moved in with her.

He remembers himself as a partly formed man. He had an unruly imagination and a gift with words but no clear idea of how to proceed in the world. He’d been living off spaghetti-os. The first meal Joan made for him, in her tiny apartment, was an authentic lasagne that an Italian friend had taught her how to make. She didn’t have a kitchen, just a few bricks, a board, and an electric burner. They washed the dishes in her bathtub.

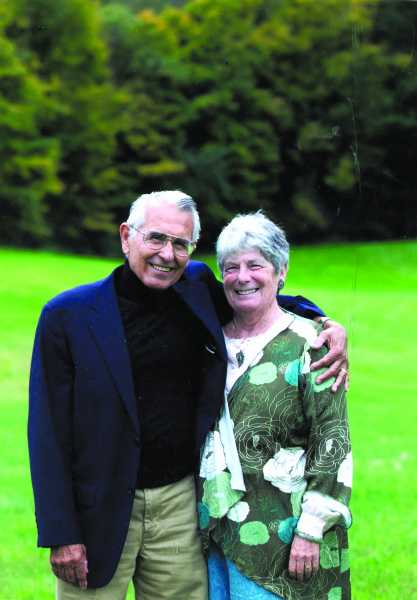

Two months later they married. They would spend the next 51 years together. Their life was a highly moveable feast. They traveled the globe, wrote books, taught at universities, lived a New York literary life and later a breezy California idyll, built a far-flung community of fellow writers and readers, had two sons, lost one tragically, and throughout five decades found an ever-deepening love that continued to bloom right up until Joan’s dying day, which was on August 18, with Ron at her side in their Hermosa Beach home.

She succumbed after a short battle with cancer. Ron would find out only after Joan had passed that he’d fulfilled her last wish. A day after her death, he received a note from an old friend and fellow journalist, Marjorie Rosen.

“I have been thinking about a moment that occurred a few years ago,” she wrote. “Around 10 of us were at a restaurant next-door to the Joyce [Theater], prior to a dance concert we were attending. We went around the room, each offering up a very private wish of ours. When it was Joan’s turn, she said that she prayed and hoped that when she took her last breath, she would be looking up to see your face, your presence, guiding her into eternity. I am so happy that she achieved that wish.”

Joan completed Ron, and he completed her. “It’s interesting because their name runs together,” said Caroline McAllister, another of the couple’s oldest friends. “It’s Ron and Joan. You don’t think of them separately. You think of them together.”

They shared more than 18,000 days of life together.

“This is uncharted territory,” he said, days after her death. “You love someone so long, and then she’s gone.”

He thought about that day in the library back in 1966.

“That was one of the things I liked the most in our 51 years of marriage — the stuff we would argue about was on the level of that poem,” he said. “It wasn’t the poem that mattered. It was her passion, correctness, getting it right, and straightening me out. I see the decency and thoroughness of that. By contrast, I would have been sort of a vagrant. A beach bum, really. She was such a good student, and I always ran from the classroom. She organized me.”

“Our immediate attraction to each other was mutual, and it had nothing to do with the meaning of a poem,” Ron said. “That was just a pretext, the spark that started our bonfire. And I don’t think that as long as I’m alive, it’ll ever go out.”

The adventure beginsJoan was born in Newark, New Jersey, on March 29, 1941. Her parents were Harold and Sylvia Zonderman; he was an accountant and she worked as a secretary at a newspaper. Joan was the oldest of three siblings, two girls and a boy.

The Zondermans were an orthodox Jewish family. Harold had arrived in the United States at the age of 8 from an area in Imperial Russia that is now Belarus but at that time was called the “Pale of Settlement,” a 500 mile stretch of land between the Black Sea and Lithuania where the czars historically had directed Jews to live.

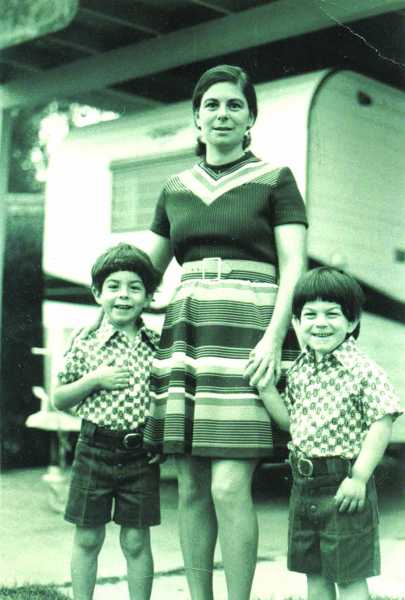

Childhood friend Sarah Otey recalled the Zonderman household as the kind of traditional home where Harold would arrive home at 5 p.m. with dinner on the table waiting for him.

“Joan was rebellious from a very, very young age,” Otey said. “Her parents were more conservative and straightlaced than mine, however they did allow her to have parties in the basement of their home. They were really lively; our family didn’t have a television, so I went to Joan’s house to watch Elvis on the Ed Sullivan show.”

Joan’s brother, Dave Zonderman, said their father ran a strict household and was particularly protective of his oldest girl.

“My father was very typical for a father of that era, very dogmatic, very disciplinarian,” Zonderman said. “He liked things the way he liked them, and he got angry when things weren’t done the way he liked them.”

Joan had an early gift for languages. Her brother recalled that her high school French teacher was so attached to his prized student that he grew upset, later, when she went to college and majored in Spanish (because she thought the teachers in that department were better). She attended Douglass College, a women-only liberal arts school affiliated with Rutgers University. At that time and place, women could aspire mainly to go into teaching, nursing, or secretarial work. At her father’s urging, she obtained a certificate to teach high school, though she had no desire to teach high school.

“We were raised to be nice to people, to study and get a career,” said her brother, who became a doctor but recalled their father suggesting that if school didn’t work out he could help arrange for him to become a sheetrock worker. “Father liked for us to learn a profession.”

Joan also had an early bent for public service and a natural inclination to side with the underdog. She worked one summer during college at a women’s prison and later, when she studied abroad as a graduate student, was right in the midst of a revolutionary hotbed at the Central University of Venezuela in which two of her friends, Peace Corps volunteers, were slain. Though she didn’t practice Judaism in her adult life, she’d grown up ingrained with “Tikkun Olam,” a Jewish concept encouraging acts of kindness performed to perfect or repair the world.

“It just means to help people,” Dave Zonderman said.

She obtained her master’s degree in language and linguistics from the University of Illinois and then, after Venezuela, arrived at UCLA to pursue her doctorate in Hispanic languages and literature. And then she met Ron.

“I’m an undergraduate. Basically, I was just trying to stay out of the Vietnam War,” he recalled. “And she probably thought that was pretty good. She didn’t know it, but I came from a military family and I was ready to go to Vietnam as another adventure. I was that stupid. I wasn’t politically aware. And she, as I discovered, was what I called a raving pacifist.”

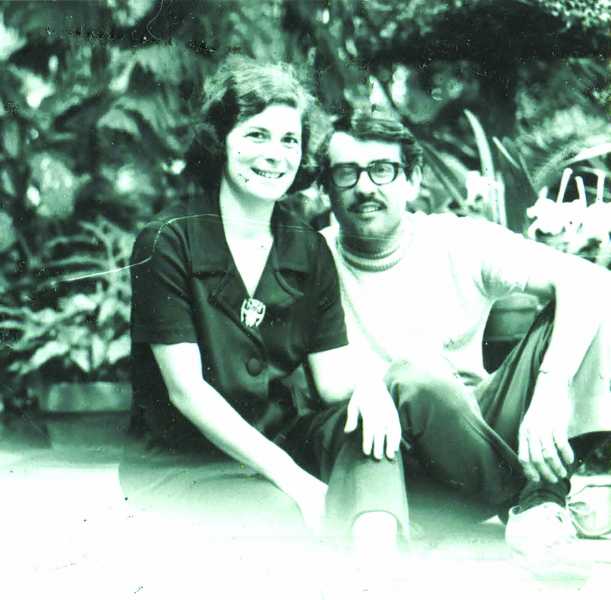

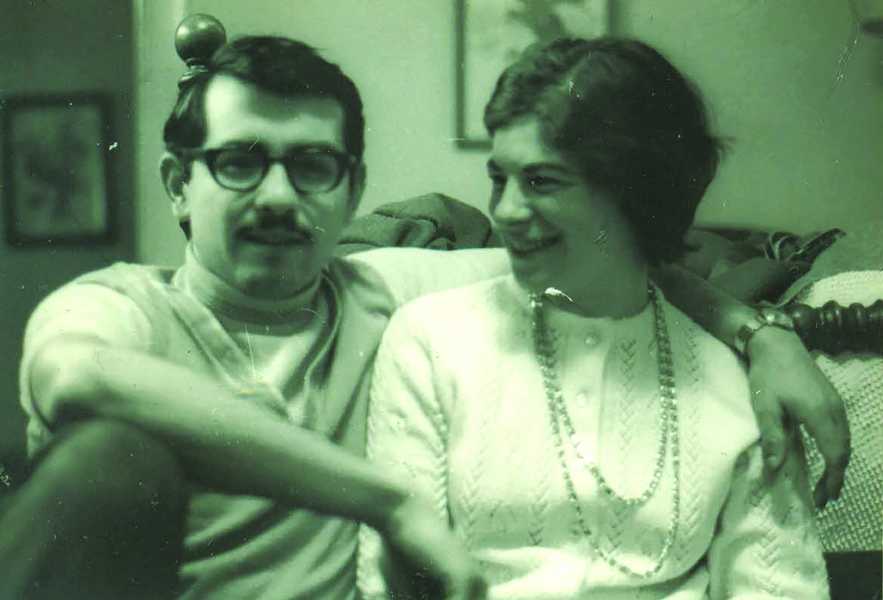

They were a beautiful couple. Ron was a lithe and graceful young man, soft-spoken with an alert, roving intelligence. Joan was petite, dark-haired and intense. They married on April 1st, 1966, before a Justice of the Peace near the UCLA campus.

“We just clicked,” he said. “The thing we clicked about most, besides the physical part, was our sense of humor. I loved her wit and her quickness. And I loved her generosity. She was so open-hearted and spontaneous. We really did things with our gut feelings, as in marrying, or having a kid.”

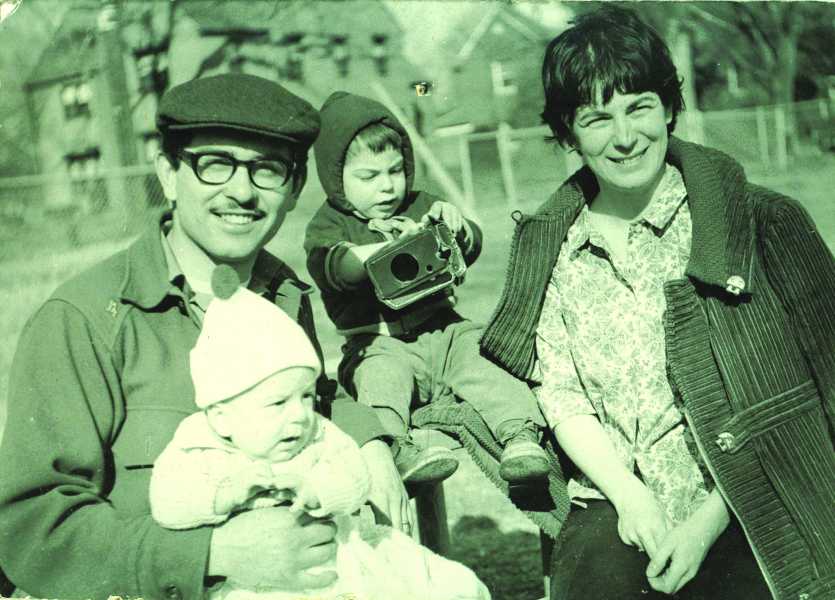

They were still at UCLA two years later when they had their first son, Michael. Ron had obtained his undergraduate degree in Spanish and then his master’s in journalism and embarked on his writing career working for the small Copley family newspapers in Burbank, Monrovia, and Glendale. Joan worked on a dissertation about a novel of the time, “Guzmán de Alfarache” by Mateo Alemán; her work was eventually published by a distinguished academic publisher, Tamesis Books, and was titled, “The Unrepentant Narrator.” It was an appropriate phrase for the life the couple were embarking upon — a shared life of story and unapologetic adventure.

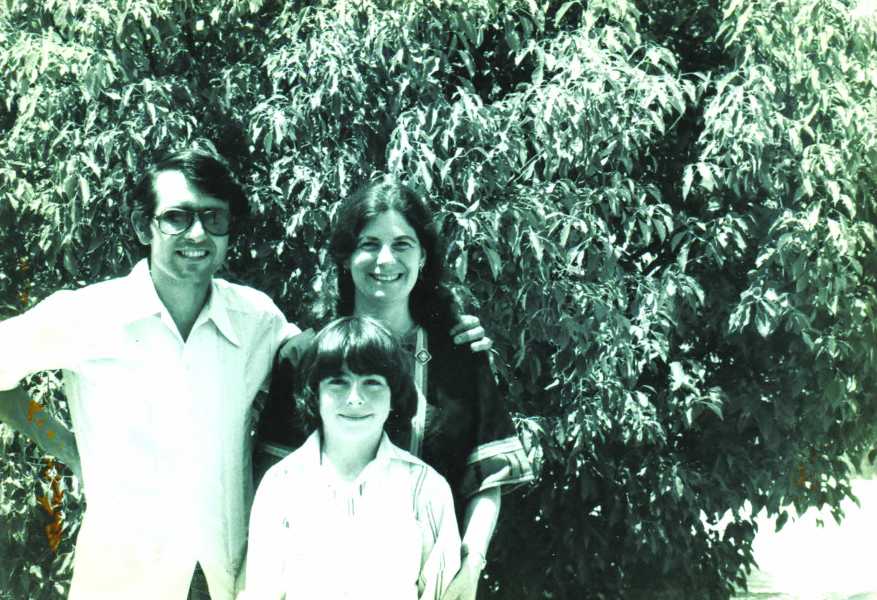

Little newspapers didn’t satisfy Ron’s broad sense of curiosity for the world. He took a job with the Caracas Daily Journal. And so with a four month old child in tow, Ron and Joan packed up and moved to Venezuela.

“Practically,” Ron said, “on a whim.”

Part II: Travels, tragedy, and a life Hermosa.