After learning in Hermosa Beach, McGinnis-Drummy took on surfing world

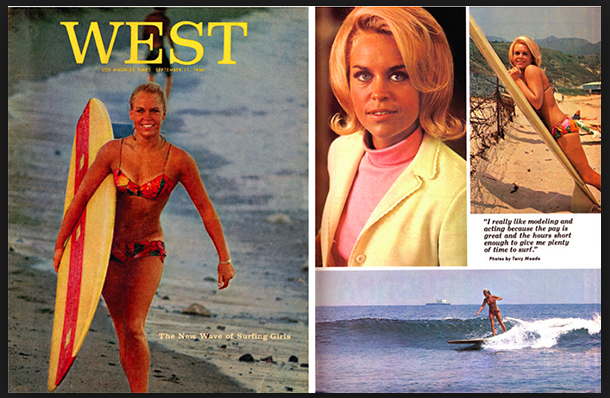

A 1966 photo spread of Mary Lou McGinnis-Drummy from West, the former Sunday magazine for the Los Angeles Times. Image courtesy Jani Lange

After reaching the heights of women’s competitive surfing in the 1960s, Mary Lou McGinnis-Drummy became the first woman to star in a feature surf film. But it would be wrong to think of her story as one of constant struggle against a male-dominated surf establishment. Learning to surf in Hermosa Beach in the 1950s, she found a supportive environment in which being a woman did not make much of a difference.

“Everybody was really cool, they were really friendly,” McGinnis-Drummy said in an interview. “It was a great opportunity learning at that beach.”

McGinnis-Drummy is one of three people who will be inducted to the Hermosa Beach Surfer’s Walk of Fame on April 29. Over her lengthy career, she won top contests, explored new waves, and became an important organizer of surfing competitions, serving as a founder of the Women’s International Surfing Association.

Donald Craig, a 2009 inductee to the Surfer’s Walk, said that McGinnis-Drummy would be an excellent addition to the Hermosa heritage site.

“Mary Lou has been involved with our sport since her early days of competition, and has not only mentored many great surfers throughout her 40-year career, but has added the credibility that our sport so much needed,” Craig wrote in recommending her for induction.

Now living in San Clemente, McGinnis-Drummy spent her childhood years in the Chatsworth neighborhood of Los Angeles, a deep suburb of the San Fernando Valley better known for horse property and high school baseball than for producing surfers. But her family spent summers, spring breaks and other scattered holidays at a beachside house in Hermosa, which marked her initiation into the waves.

She got her first board, a 9’6” Velzy-Jacobs made from balsa wood, as a Christmas present. She hauled it to and from the beach in front of her house, only later noticing a solution to the problem of carrying the notoriously heavy boards of the era.

“At that time when I got my first board, all the guys had wooden lockers down on the Pier that they kept their boards in,” McGinnis-Drummy said.

McGinnis-Drummy made 20th Street, just in front of her family’s beach house, her home break.

In a sign of the local loyalty that defined the surf-club mentality of the era, she said she never saw any other girls surfing there, but that there may well have been others further up or down The Strand.

McGinnis-Drummy’s halcyon reminiscences are a reflection of the period of surfing she grew up in. She came of age in the “Golden Era” between the end of World War II and the release of “Gidget” in 1959. Although “Gidget” is a movie about a girl surfer, it is widely credited with sparking the broader national fascination with surfing, and the movie launched thousands of people — far more of them men than women — from their inland homes to surf shops and beaches, packing lineups for a generation.

There was little reason to be aggressive, McGinnis-Drummy noted, when the surf was not crowded.

“It was the time that I was surfing: I had the whole coastline I got all the waves I wanted, every place I went,” she said.

That is not the case today, she noted. Some of the sport’s continued growth in popularity comes from more people living near the coast, or the proliferation of surf schools, she reasoned. But given the joy wave riding provides, its growth may have been inevitable.

“Every person that was surfing in the ‘50s, they all had kids. And their kids are surfing, and all their grandkids are learning how to surf,” she said.

McGinnis-Drummy ventured farther afield with rides from her mom, eventually settling on her three favorite waves: San Onofre, Rincon and Malibu. As she got better, she compiled an impressive record in contests like the Santa Monica Mid-winter Surfing Championships and the U.S.Championships at the Huntington Beach Pier.

She also launched a film career while competing. She appeared as an extra in the Frankie Avalon-Annette Funicello beach movies, and a surfing stunt double for Sharon Tate in 1967’s “Don’t Make Waves.” She also starred in “Follow Me,” a documentary in which a “Surf Corps” travelled around the world searching for waves, a la “The Endless Summer.” A trailer for the film promises a journey into the “bold, beautiful, stoked world of today,” and shows McGinnis-Drummy in India, riding an elephant that carries her board with its trunk.

She did all of this as a single mother, raising her son Erin. She got some help from her mother, and would look for work in the afternoons and nights, but her lifestyle often meant that Erin accompanied her to the beach.

“Mostly I just took him with me. He caught lizards and horny toads on the sand,” McGinnis-Drummy said.

As more women got interested in surfing, McGinnis-Drummy became more involved in creating opportunities for them to compete. She helped found the Women’s International Surfing Association in 1975. The association eventually merged with others and became the Western Surfing Association, which today holds 11 annual events for men and women along the West Coast. McGinnis-Drummy still organizes and runs the events, which can feature more than two dozen divisions, ranging in age from under 9 to over 60, and heats for adaptive surfers.

Looking back on her time in surfing, McGinnis-Drummy said she was especially pleased to receive the honor in the place where she first learned to ride waves.

“It’s absolutely fantastic, and one of the greatest honors of my life,” she said.