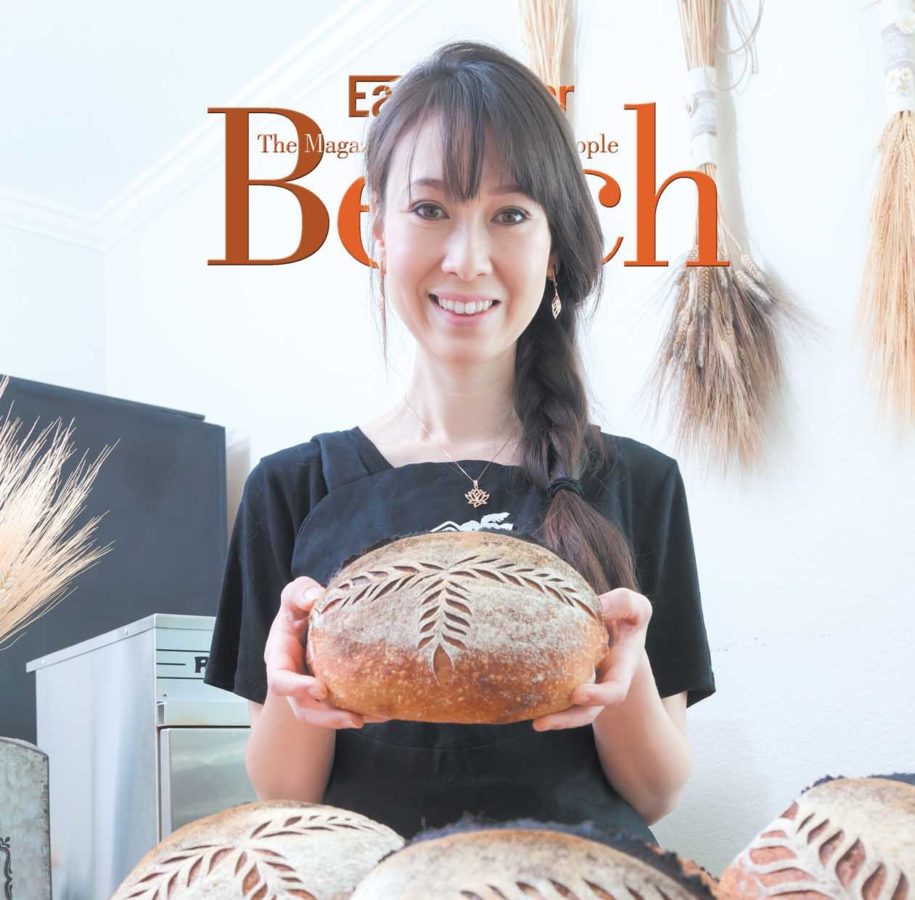

Beach people – Time to rise with Lisa Clayton

Lisa Clayton had accepted that she would need to rise at 4 a.m. to turn on her oven. The oven, imported from Belgium, contains bricks laid on top of heating elements. Food is cooked through heat stored in the stones. This allows the interior to retain a constant temperature despite openings and closings of the oven door. The oven mimics the ancestral hearth style of cooking, but requires a long preheating period, about two hours.

Lately, Clayton has been able to get up closer to 6 a.m., thanks to a timer she can program to preheat the oven. This sleep-saving stratagem, though, should not be mistaken for dread of entering the kitchen.

“I think I’ve always been drawn to procedures in cooking more than to the actual output. Obviously it’s got to taste good and that’s why you cook. But I’ve always been attracted to the more involved recipes,” she said. She mentioned the experience of flipping through a cookbook, and zeroing in on the oft-skipped recipes that spill over onto multiple pages. “People think, ‘Ah, you cook for two hours and then it’s gone in 10 minutes.’ Although I understand that, for me, those two hours are enjoyable.”

The Redondo Beach resident is the founder of the Beach Cottage Bakery, an artisanal sourdough operation she runs out of her home. What began as a hobby has become a small business and a pulpit from which to preach the virtues of an older and slower way of getting our daily bread.

I had presumed “sourdough” was more marketing gimmick than baker jargon, an imprecise word meant to evoke cable cars and fog-shrouded views of the Golden Gate Bridge. But as Clayton is eager to explain, “sourdough” is a term of art, or perhaps more properly of science. It is bread made through fermenting bacteria — the “sour” in sourdough is a reference to the acid that is a byproduct of fermentation — and until the rise of industrial food production, almost all bread people ate was sourdough. The aphorism “Civilization began with fermentation” is often attributed to Faulkner with a wink at the novelist’s love of booze. But sourdough is also as old as agriculture, one of the earliest examples of humans using their ingenuity to make the world more nutritionally useful.

Clayton feels oddly comforted by the fact that she is a mere blip in sourdough’s lengthy history. Though she has only been baking sourdough for about three years, and has thought of it as a commercial enterprise for just under a year, her loaves’ striking appearance and beguiling flavors have already won her devoted fans.

Hermosa resident Erin Getty heard of Clayton through a post on NextDoor about delicious sourdough bread. Her interest was heightened by her first glimpses of Clayton’s handiwork, which she described as “so visually edible. You want to eat it with your eyes.” When Getty tried it for the first time, the effect was profound. She felt as if she had been transported to a different time and place, one with different pacing and priorities than those of 21st-century Southern California.

“It really is ‘a country loaf,’” Getty said, referring to the name that Clayton gives to her sourdough standby, made from a mix of rye, spelt and wheat flours. “It’s something you would get in the countryside in England or Ireland. Something that the local pub would serve,” she said.

It is no accident that Getty discovered Clayton through social media. Before launching the Beach Cottage Bakery, Clayton documented her journey through sourdough on an Instagram account, Sourdough Nouveau. The account featured shots of painstakingly decorated loaves: lattices, fleurs-de-lis, and even etchings of animals like cats and deer on her crusts, popping out at the viewer through intricate acts of shaping and flour dusting. One, a loaf darkened with activated charcoal, featured tiny white markings along one side that, upon closer examination, revealed themselves to be stars; it was baked as a “tribute loaf” to honor the passing of astrophysicist Stephen Hawking. The account racked up mentions in food media, and Clayton eventually amassed 50,000 followers.

Seth Davidson met Clayton during this period of rising social media fervor. Davidson, an attorney who runs a Torrance-based bicycle injury firm, came to know Clayton through her husband Alex, with whom he rides. At the time, Clayton was selling her hand-made jewelry, and thought of baking as more of a side project than a vocation. He said the attention Clayton was getting for her bread surprised her, and that she was uncertain what to do about it.

“She was not a full-time baker. That was an evolution that I think came hard, though perhaps inevitably, on the heels of her Instagram account,” Davidson said. “But the photos she posted were so extraordinary. It didn’t make any sense to only leave it on Instagram.”

Clayton launched the Beach Cottage Bakery late last year as an online subscription service. She offered her country loaf every week, along with a rotating array of new experiments. Last month, after Beach Cottage began attracting devoted local adherents, she began selling her bread at the Hermosa Beach Friday Farmers Market.

The Farmers Market enables Clayton to tap into the creative spirit that drives her. Relying exclusively on preorders, she said, sometimes made her feel constrained in the kinds of bread she could devise.

“The farmers market allows me to just go, you know what, I’m going to try this crazy bread and see how it goes,” Clayton said.

Although she still accepts specialty orders, Clayton has mostly set aside the baroque ornamentation that launched her to social media stardom; there simply are not enough hours. Baking days, Clayton said, are “ruled by timers going off every 10 minutes or so.”

But her work retains elements of unmistakable beauty. Her oval-shaped loaves and spear-like baguettes bear ridges that grow and recede along the surface of their crusts with the practical elegance of a scrivener’s calligraphy. Like canyons etched by eons of flowing water, they are the product of something best understood by thinking about time in a very different way.

“Because sourdough is a lengthy process, one of the biggest things you need is patience. Last week when I was waiting for the dough to rise, I thought, I totally get why they invented fast-acting yeast: I need to be at the farmer’s market at 12, and this guy’s not rising. There are so many variables to control. But at the same time, letting go of control is one of the most important things.”

Clayton began selling her bread as an online subscription service. Last month, she began appearing in a booth at the Hermosa Beach Friday Farmer’s Market. Photo

Transformation

In her mid-20s, Lisa Clayton was living in London, working in public relations for a pharmaceutical company, and returning home crying.

“I remember saying to my husband, I just feel like I’m trying to squeeze myself into this mold, and I don’t fit, and it’s really uncomfortable, and I have no self-esteem or confidence because I feel like I’m terrible at it, and all my colleagues hate me,” Clayton recalled.

Clayton had graduated with a degree in biology from Oxford University. The PR position was her third since graduating. She had taken up jewelry-making in between jobs, and began selling what she made at London markets. The craft brought her some joy, but it also reminded her of how unhappy she was in her working life. Clayton felt adrift in ways that a sociologist or demographer of Millennials would recognize. Over the course of our interview, she laid out the mix of emotions she felt in this period, seemingly unaware that it would like take super powers to reconcile them all: impatience to enter the “real world;” desperation to “justify” her degree; the “need to be engaged in something more creative”; and, perhaps most challenging of all, the urge to “do something that I felt had meaning.”

She left England with her husband, who works for a company that writes financial software, when he was offered a temporary posting in a suburb of Detroit. One year grew into two, and then he took another job in Los Angeles, and they moved to the South Bay. They rented a small home in Redondo that became the inspiration for the “Beach Cottage” name.

Their landlord, Vinka Lucio, first noticed Clayton through the vegetables she had planted in the garden that the home shared with other units. Later, a fellow tenant told her about Clayton’s baking. Lucio began following Clayton on Instagram. When they began talking, Lucio encountered someone whose passion was evident, but was not quite confident enough to fully devote herself to it.

“I think her standards are very high, and it’s clear how deeply knowledgeable she is. She thinks, ‘Well this wouldn’t go well, but do you want to try it? And my husband and I would think, Are you kidding me?’” Lucio said, her voice rising and then receding in remembered awe.

Clayton admits that some of the uncertainty and self-doubt during her years in London held her back from embracing baking as a career.

“I was worried that baking was a manual thing, maybe not something as intellectually demanding. But I’ve been finding that it is stretching my multitasking abilities to the absolute. And is it actually very challenging: my mind is as active as my body is,” she said.

Unsurprisingly, given her tendency to intellectualize, Clayton was nudged into baking in part through a book. She came across “Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation,” in which food journalist Michael Pollan examines the science, history and technique behind various kinds of food preparation. Pollan explained that, when it comes to sourdough, “control” is “far too strong a word” for what the bread baker does.

“It’s a little like the difference between gardening and building. As with the plants or the soil in a garden, the gardener is working with living creatures that have their own interests and agency. He succeeds not by dictating to them, as a carpenter might to lumber, but by aligning his interests with theirs,” Pollan wrote.

Here at last was something that appeared to resolve the conflicting impulses Clayton felt. When I mentioned the old saying that “Cooking is an art, baking is a science,” she pounced.

“Before I started making bread, I would have agreed. I mean, you don’t want to just eyeball, this much baking soda,” she said, holding up her hand with her thumb and forefinger separated by perhaps half an inch. “Because it is a chemical reaction. But with bread making, and sourdough making in particular, because you’re working with a living culture, everything that’s going on is more of a biochemical process than just a chemical leavening agent. So it can be approached more like an art.”

Like other fans of Clayton’s bread, Davidson, himself an amateur sourdough baker, sees this blending of characteristics as an essential aspect of her loaves.

Along with her standby country loaf, Clayton experiments with an assortment of breads made from rarely seen grains. Photo from Instagram

“She’s a very unusual person. She’s a scientist: that explains part of her approach to baking, but she’s also an artist. I’d say the first 50 percent of her is scientist. The second 50 percent is artist. And the third 50 percent is, she has a profound appreciation for real food. I think that adds up,” Davidson joked.

Diving into the history of breadmaking has also helped give Clayton a deeper sense of purpose. She mentions that the marks on top of her loaves are not just eye-catching but functional: they allow her to determine where the bread’s moisture-driven pressure is released. This process, known as “scoring,” dates back centuries, to a time when most people did not have ovens in their homes. Instead, each town would have a communal grain mill and hearth oven. People would assemble their dough at home, then bring it into town to be baked; scoring began as a kind of signature, “so people knew which one was theirs, and didn’t end up with the crummy one their neighbor made,” Clayton joked. The scientist in Clayton may thrill at digital scales and the gradients of oven dials, but she can also come across as wistful about what has been lost in a world of fast-acting yeasts.

“Now we go to supermarkets. And as friendly as cashiers might be, you just can’t form a connection,” like the one created by sharing an oven, she said.

Clayton’s belief in bread’s communal power signals the next chapter of her baking business: workshops teaching people how to bake their own sourdough. Like everything she does, she is nervous about getting it off the ground. But along with helping her learn to surrender control occasionally, her experience in sourdough has provided what long eluded her: the ability to see the value in doing what makes her happiest.

“I guess I started seeing that food can be a lot more than food; it can bring people together. People have always gathered around food; it’s a big way we can show our love and caring for each other. And it definitely has been that for me,” Clayton said.