“The Central Park Five” – Spirited and gut-wrenching opera by Anthony Davis

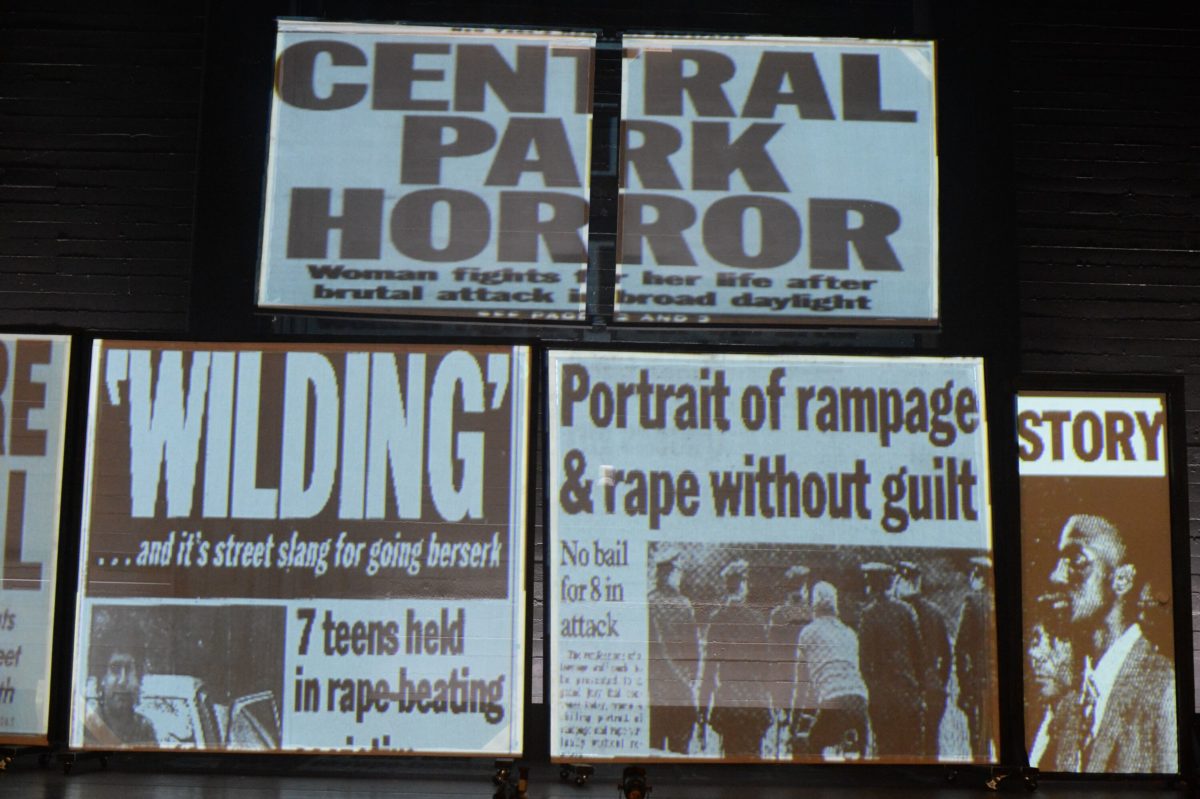

Newspaper headlines about the tragedy in New York City’s Central Park, 1989. Photo by Keith Ian Polakoff

a stunning opera by Anthony Davis premieres in Long Beach

Very few operas will get you fired up, but that’s what Anthony Davis set out to do with “The Central Park Five” and he’s succeeded. This riveting work, focused on the accusation, trial, and conviction of five African American and Latino teenagers, held in connection with the 1989 rape and brutal beating of a young female jogger in New York’s Central Park, had its world premiere on Saturday at the Warner Grand Theatre in San Pedro. Commissioned by Long Beach Opera, it’s being directed and produced by the company’s artistic director, Andreas Mitisek.

In Davis’s words, “I want the audience to have an emotional experience that involves identifying with the characters and putting yourself in their place.”

Despite having taken place 30 years ago, the narrative remains socially relevant, and in its rawness and immediacy feels especially timely in a way that other operas dealing with recent sociological or political events do not. Of course, there aren’t many. “Nixon in China” and “The Death of Klinghoffer” are often cited (another is the little known “Fallujah,” presented by Long Beach Opera a few seasons past). However, the work to which I might compare “The Central Park Five,” by way of sheer intensity, is Bob Dylan’s “Hurricane,” about the unjustly imprisoned Ruben Carter, on his “Desire” album.

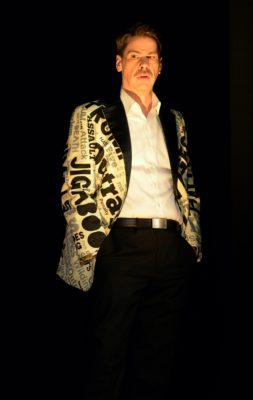

Zeffin Quinn Hollis as The Masque. Photo by Keith Ian Polakoff

A few in particular, who would come to be collectively known as the Central Park Five, included Antron McCray (portrayed here by Derrell Acon), Yusef Salaam (Cedric Berry), Raymond Santana (Orson Van Gay), Korey Wise (Nathan Granner), and Kevin Richardson (Bernard Holcomb). Despite an effort on the part of Davis and librettist Richard Wesley to individualize them, they are essentially one character, which we may call The Falsely Accused (although no one knew that for certain at the time, apart from the five themselves). When they were arrested, two of the boys were 14 years old, two were 15, and one was 16.

Despite being staged in a sumptuous, Art Deco theater from the golden age of cinema, “The Central Park Five” has an austere and minimalist set, movable panels and doors, enhanced only by video projection (also designed by Andreas Mitisek) and the rather noirish lighting of Dan Weingarten. After a scene with the five accused, post-exoneration, we’re back on the streets, presumably of Harlem, with a character identified in the program only as The Masque (Zeffin Quinn Hollis, the recent star of LBO’s “In the Penal Colony,” composed by Philip Glass and based on the Kafka story). The Masque slithers like a Raymond Chandler gumshoe but he literally wears his prejudices on his sleeve, not to mention the rest of his white jacket which is printed with what, taken together, constitute his belief that all African Americans are hoodlums from the moment they’re in diapers.

Hollis later assumes the role of other characters, all of them unsavory and looking for a conviction.

While the boys are being detained for questioning, the young jogger, 28-year-old Trisha Meili, has been discovered in the park and is near death. She’s in such serious condition that in the hospital she’s given her last rites.

Now everything takes a much darker turn.

Bernard Holcomb as Kevin Richardson,Nathan Granner as Korey Wise, Derrell Acon as Antron McCray, Cedric Berry as Yusef Salaam, and Orson Van Gay as Raymond Santana. Behind them, their parents, l-r: Joelle Lamarre, Ashley Faatoalia, Lindsay Patterson, and Babatunde Akinboboye. Photo by Keith Ian Polakoff

The heart of the opera has to do with the young men proclaiming their innocence while being interrogated for several hours. Or, it might be more accurate to say, psychologically assaulted. The pressure, coercion, and brow-beating includes such strong-arm tactics as telling each one that the others have implicated them, and, worse, they are led to believe that if they simply “confess” then they can go home. In such situations, as we know, people will say anything just to get the torture to stop. And that seems to have been what happened here.

But we have to remember that feature films and plays and operas aren’t necessarily objective documentaries. Wesley and Davis appeal to and manipulate our emotions, which is often what art does, but in this case we really don’t have time to reflect and so are pulled along in a storyline that ultimately is fairly black and white. Since we know the outcome of this tragic event, that the plaintiffs were sentenced to, and served many years in prison, we’re naturally going to sympathize with them. But what if we didn’t know the outcome? What if the story was reset in another time and place? Would our minds be made up so easily?

Davis originally wanted two sets of performers for the accused boys, teenagers and adults, but the budget only allowed for the latter. And so, another question: How does seeing the 14, 15, and 16 year-olds portrayed by mature men affect our reactions to the drama?

When the news gets out about the horrendous assault, the media dives in headfirst. The term “wilding” comes to mean marauding gangs of lawless youths, flash mobs that run in “wolf packs” and commit unspeakable crimes.

The common citizen is outraged, none more so, it seems, than real estate mogul Donald Trump, who takes out full-page ads in New York’s four main newspapers. He’s sure the kids are guilty and wants the death penalty reinstated so that they’ll hang.

All along, there’s been no incriminating evidence to prove that the five detainees were responsible for the assault on Trisha Meili. Specifically, no DNA evidence.

Zeffin Quinn Hollis as The Masque, Thomas Segen as Donald Trump, and Jessica Mamey as the District Attorney. Photo by Keith Ian Polakoff

That would be fine, of course, except that Davis overplays it. Trump is a buffoon and a blowhard in real life, but he becomes more of a caricature here, and a scene where he’s sitting on his golden toilet, ranting with his pants down to his ankles, needs to be scaled back simply because it jeopardizes the integrity of the overall work. A little goes a long way and a lot goes too far.

The cast also features Babatunde Akinboboye as Raymond’s father, Ashley Faatoalia as Antron’s father, Joelle Lamarre as Antron (and Kevin’s) mother, and Lindsay Patterson as Yusef’s mother. When Lamarre, in the courtroom, sings out of pain and desperation for her son, how can we not sympathize with a mother’s plight? It’s a heartbreaking moment, and so is the scene when the young men think they’ll be exonerated after Meili comes out of her coma. Surely she’ll tell everyone that it wasn’t them who committed the crime. It seems to be their one hope, but the young woman can’t remember a thing about the attack.

The boys are sentenced and locked up. The four youngest would each spend over six years in jail, and Korey Wise, the eldest, nearly 13.

And then, in 2001, a serial rapist, Matias Reyes (Akinboboye), confessed to the crime, and furthermore his DNA matched the DNA found on and near the victim. Case closed? Not everyone, including Trump, accepted that. In the end, civil lawsuits were filed against the City of New York, as well as those (police officers and prosecutors) who had pressed for a conviction no matter what. After all, people had demanded justice, and, barring that, a scapegoat. It wasn’t until 2014 that a monetary settlement ($41 million) was reached.

The opera ends on a “jubilant” note: The cast at the front of the stage with the words “And we’ve finally come home.” In other words, at long last justice has emerged. It’s a bit of a pat ending, but one that suffices. And yet imagine if Matias Reyes had never confessed.

Nathan Granner as Korey Wise, Cedric Berry as Yusef Salaam, Derrell Acon as Antron McCray, Orson Van Gay as Raymond Santana, and Bernard Holcomb as Kevin Richardson. Photo by Keith Ian Polakoff

Opera music is rarely edgy, rarely used to underline tension and turmoil, but the score here, conducted by Leslie Dunner and performed by the LBO Orchestra, shows what the genre is capable of. Some of us might never have guessed. From the opening moments to the closing scene, my eyes and ears never left the stage.

Although the opera lacks subtlety in its overall effort to nail down its message about social prejudice and injustice, and despite manipulating our responses to the characters and their situation, “The Central Park Five” is a stunning achievement, fully alive and vibrant. I hope it travels far and is seen by many people in many cities throughout the country.

The Central Park Five, composed by Anthony Davis with a libretto by Richard Wesley, is being performed on Saturday, June 22, at 7:30 p.m., and on Sunday, June 23, at 2:30 p.m., in the Warner Grand Theatre, 478 West 6th St., San Pedro. 130 minutes, with one intermission; sung in English with English supertitles. Pre-opera talk, one hour before curtain. Tickets, $150 to $49. Call (562) 470-7464 or go to LongBeachOpera.org. ER