Gritty, gritty, bang bang: early Moriyama

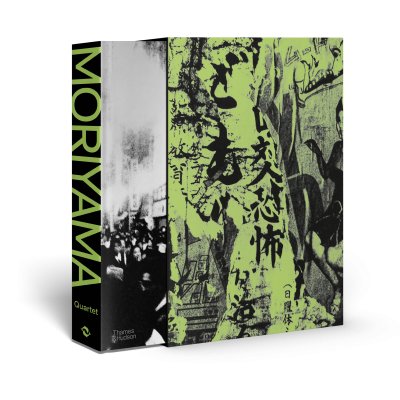

“Quartet: Daido Moriyama,” ed. By Mark Holborn (Getty Publications, hardcover with slipcase, 440 pp., $75)

by Bondo Wyszpolski

“Daido Moriyama: Quartet,” edited by Mark Holborn, is a striking and even lavish publication that reproduces the images from the photographer’s first four volumes: “Japan, A Photo Theater” (1968), “A Hunter” (1972), “Farewell Photography” (also 1972), and “Light and Shadow” (1982). They are all printed on slick, heavy, glossy paper.

A little bit about Moriyama himself, who was born in 1938. He was six years old when the war ended and Japan surrendered, and therefore grew up under the American occupation. As Holborn notes early on, “Moriyama is now an international figure whose visual language was born in the back streets of Osaka and Tokyo’s Shinjuku and Shibuya districts, yet he is understood in the cities of Europe and America.”

The last part of that sentence may be true, but nothing exists in this volume to support it. Could someone explain? At any rate, Eikoh Hosoe and Shomei Tomatsu were influential for Moriyama, but the only photographs reproduced in the book are those taken by Moriyama, so we have no points of reference.

Hosoe may be best known to Western audiences for his photographs of writer Yukio Mishima. When Moriyama moved to Tokyo in 1961 he found employment in Hosoe’s studio, where he remained for two years.

What Moriyama came away with after working closely with Hosoe will have to be sought elsewhere. However, as Holborn writes, “From the publication of his first book, Moriyama displayed the strokes of an audacious graphic sensibility with a fierceness evident only in the work of William Klein in Paris.”

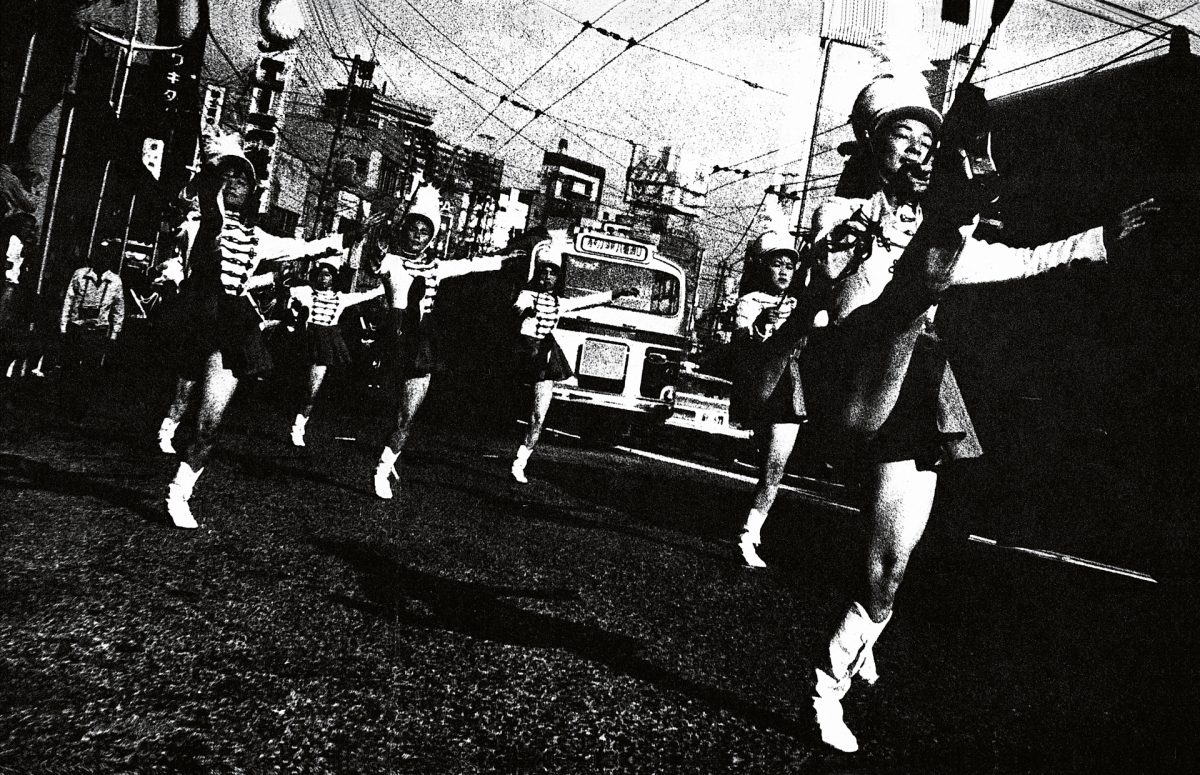

A Photo Theater

Regarding “Japan, A Photo Theater,” Moriyama writes that “It was meant as an experiment. I wondered if I were to remove certain recent photographs from their original context, treating them as fragments, then recomposed these fragments in a completely new context, making each image equally flat, then I might be able to reconstruct a reflection of the confusing views that exist in daily life.”

As he also says, “By taking photo after photo, I come closer to truth and reality at the very intersection of the fragmentary nature of the world and my personal sense of time.”

Holborn further clarifies this: “Performance, the act of making the image, of ‘seizing’ time, was Moriyama’s priority. The fragmentary nature to which he refers created the premise for his first book.”

Now, what can we say about this early collection?

Farewell Photography

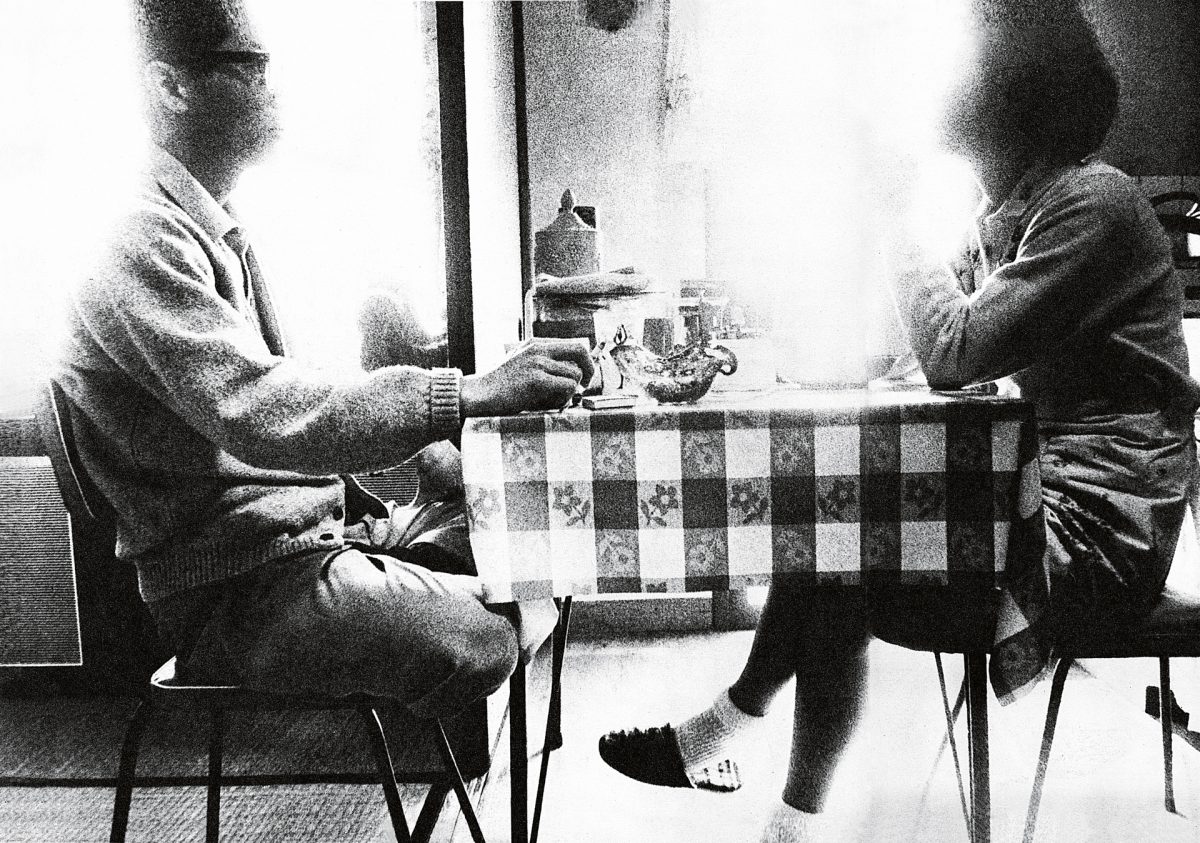

One thing, however, that we can say for sure is that these images do not seem contrived, posed, or stagey. Which is to suggest that this is like driving through a town at night without headlights.

This is true of the second portfolio, “A Hunter,” which was framed as a sort of reply or challenge to Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road.”

The introduction to this section, by Tadanori Yokoo, a noted graphics designer, comments on Moriyama’s body of work: “Some may call them filthy, but that would be a gross mistake. They are not filthy at all. They are frighteningly beautiful.”

Furthermore, “He takes pictures from the point of view of a Peeping Tom or a rapist. For me they are sex fantasies that arouse dormant tendencies in myself. The eyes peering from the windows of a moving car or from the shadows are those of criminals. His pictures are like someone who talks without looking people in the eye.”

Farewell Photography

Good point. Not just what the images depict, I would add, but in how they’re framed and printed. The graininess, the harsh contrast, what seems like grit sprinkled on puddles of oil — that also comprises Moriyama’s self portrait.

The third portfolio pushes the envelope of genteel picture-taking, and “Farewell Photography” is a work that’s raw and stripped down to its essentials. Moriyama says that once he settled on the title he “began to collect the negatives. My attention was caught by those disregarded shots at the end of rolls of film. I instinctively picked out those I found weird or odd in some way. I separated out anything with a clearly discernable image. The book was to be a collection of curiosities for which I even gathered scrapped and trampled negatives from the darkroom floor… When I had enough of those loose images, I began to print in a mechanical, almost indifferent manner. Printing quickly was never an issue from the outset and there was no retouching whatsoever.”

Shomei Tomatsu once said to Moriyama that “Photography is haiku,” but with this volume it’s like punk rock at its extreme. Again, stripped down and raw, and visually irreverent. Just compare this to the carefully composed and lit fashion shots of Herb Ritts.

There’s a 10-year gap between “Farewell Photography” and “Light and Shadow”; a better title for the latter might be “Bright Light and Darkness.” As Holborn notes, “This was Moriyama with the blackest blacks and not white borders.”

This last portfolio, with its images still grainy, has a sharper focus that often makes them crisp, allowing details to emerge that were not evident in the earlier books. While still unmistakably Moriyama, I think these pictures are easier to approach.

A Hunter

Moriyama is often labeled as a street photographer, and as if embracing that designation he has compared himself to a stray dog when he’s out prowling with his camera. He wanders as if aimlessly, not even stopping when something catches his eye but simply pointing his camera in that direction and, without looking into the viewfinder, clicking the shutter without pausing or breaking his stride. Seemingly, it comes down to chance and circumstance.

“Quartet” may not be the best introduction to Moriyama’s work — unless, metaphorically, you’re fine with being tossed into a swimming pool while fully dressed — but it does pack a big wallop, like it or not, and whether you swim with it or climb out of the pool as soon as possible.

But remember, this is just the start. Moriyama’s early years. There’s another body of work, from the early ‘80s to the present, waiting to be delved into. ER

One Response

Maybe punk rock is a form of haiku. … Haiku doesn’t have to be always about the delicate in life. Anyway, bravo on your dissection of his early work.