Robert Couturier: Still imaginative at 92

“Young McDonald Will Have a Farm,” by Robert Couturier: “As more disparate objects appeared on my worktable they began to connect in my mind, and pretty soon the theme appeared evident. They found their niche as a predictor of a familiar song.”

Nonagenarian Robert Couturier isn’t through making art

More often than not, when we purchase an item or receive a gift on some special occasion, we unwrap it quickly and then discard the packing material. We don’t even give it a second thought. But Robert Couturier, who refers to himself as “retired half engineer, half artist, and half kidder,” started coming across packaging items that, in his opinion, didn’t merit trashing. Therein lies our tale.

“With no particular direction, nor philosophy, but definitely with tongue-in-cheek,” Couturier says, “I followed the inspiration instigated by the boxes themselves.”

So he began to reconfigure them in ways he found pleasing.

Robert Couturier. Photo

Couturier lives in Redondo Beach, a stone’s throw from Palos Verdes Estates and another stone’s throw from the beach. He’s a widower now, after having been married for 70 years. One can sink into inactivity at any age, particularly after losing a longtime spouse, but at 92 Couturier is still spry, riding his bicycle, and sharp as a tack. When he laughs, which is often, it’s closer to a snickering laugh reminiscent more of a schoolboy than a patriarchal grandfather.

“So, having nothing better to do than look at the ocean,” he says, a twinkle in his eye, he began making a variety of 3D collages or assemblages with the starting point being high-end packaging. The results occasionally provide social and political commentary, but in a humorous and satiric or or just plain whimsical manner.

“The thing grew by itself,” Couturier says. “After three weeks I said, ‘Look at that, I have seven pieces already. What did I do? How did that happen?’ I was not conscious that I was creating a flow of things.

“What stopped me for a week,” he continues, “ was that I ran out of boxes.” That’s when his children stepped in, and their children as well. “The supplies came from friends of my grandchildren: ‘Oh, I have a couple of boxes for your granddad.’

“I don’t claim to be an artist,” he’s quick to add. “If it turns out that others tell me that I am, well, so be it. I don’t care.” He laughs. “And I don’t intend to make a fortune out of it, either.”

Couturier wasn’t even thinking of showing, let alone trying to sell, the pieces he was creating. Then something came along that gave him a reason for putting his art on view and giving people an opportunity to buy it.

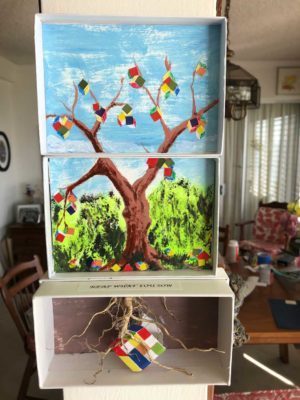

“You Reap What You Sow,” by Robert Couturier: “Forcefully driving the point home, the Rubik’s Cube generalizes the adage beyond the simple concept of seed and farming. The two-level framing structure exposes the directness of the connection between cause and effect.”

Two years ago, at the relatively youthful age of 90, Couturier reflected on life. “Here is the modus vivendi that I have used,” he wrote on his blog (papou90.blogspot.com), before listing the essentials: “Remain rational; avoid blind faith; follow your heart; remain open-minded; persevere in your goals, even to failure; search for the truth.” The last one had an asterisk beside it: “Tricky stuff here. Sometimes a lie may be an act of kindness.”

And the one point that Couturier emphasized: “If you want your life to have any meaning, it has to be a meaning for the living you leave behind.

“It does not have to be big. It has to be memorable: a work of art, an unusual act of kindness, a discovery in any field of research, an act of courage, a durable construction … anything permanent that your creativity will produce.”

As one might suspect, Couturier has lived quite a life. It began in France in the wake of the first World War. His father had served in the French army and after hostilities ceased he was sent to Poland “to re-educate the cadres for the Polish army. He had an interpreter, who turned out to be my mother. He brought my mother back to France.”

Couturier’s father was assigned to help in the reconstruction of areas in northern France devastated by the war. Eventually, when Couturier was seven, the family moved to Dijon, southeast of Paris and close to Switzerland, and to an extent that’s where the young man grew up and came of age.

He studied to become an engineer, but interrupted his schooling to help the family make ends meet. Later, because he knew some English, he was encouraged to begin a correspondence with a classmate’s female cousin who lived in New York and wanted to learn French. Letters were exchanged for two years before the correspondents at last met face to face.

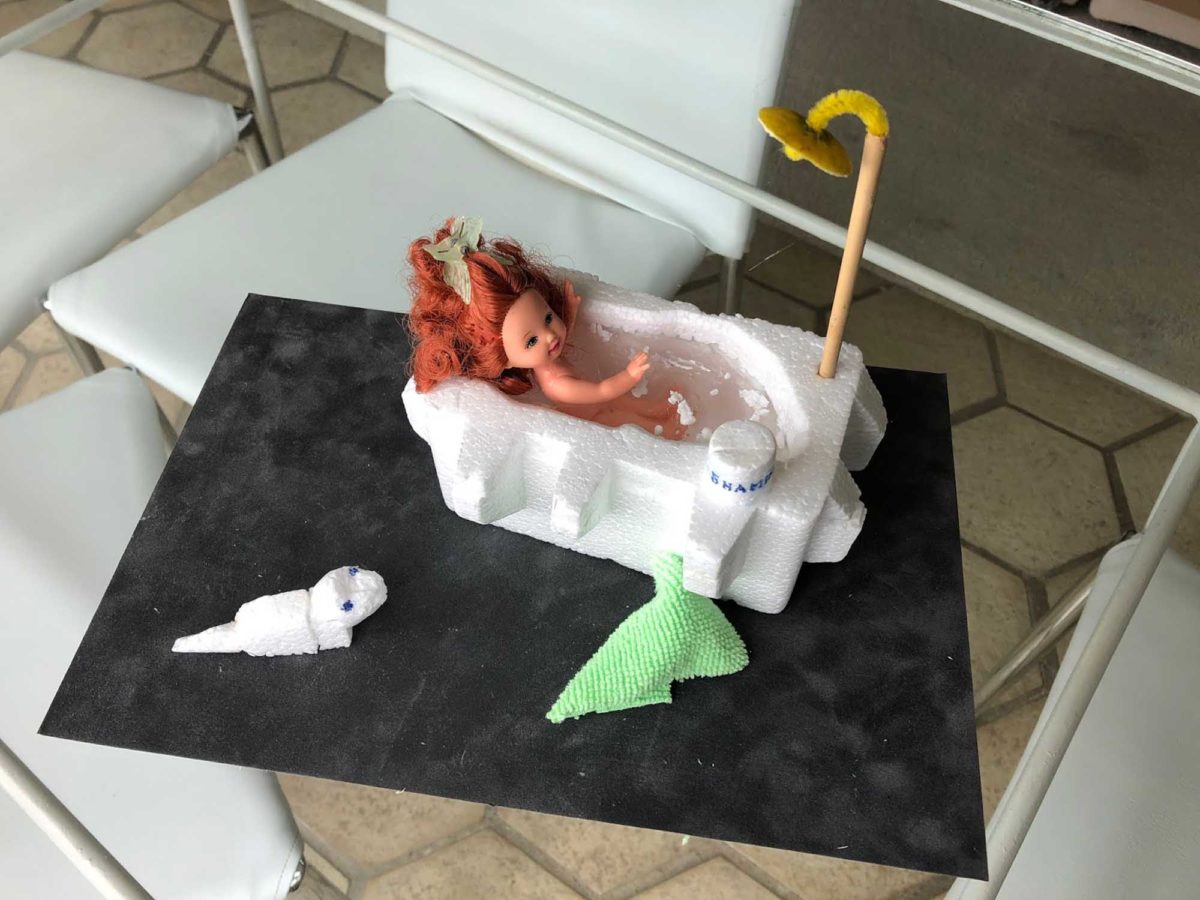

“The Bath,” by Robert Couturier: “There was no resisting the appeal of the chunk of packing polyurethane. The added human element produced the homey atmosphere of a bathroom. Worth mentioning also is the use of bamboo, lemon peel, pipe cleaner and cloth.”

Within two days they knew they were destined for one another, but in three days Marion was back to Lausanne and Robert was back to the French army where he was putting in his mandatory military service.

Reconnecting had its obstacles, of course, but true love conquers all and then some, and in June, 1949, Couturier and his bride arrived in the United States on the Queen Mary. By then, they had a six-month-old son with another following one year later. In time the family would be complete with the addition of a daughter.

“We stayed in New York for 12 years,” Couturier says. “We first lived with my mother-in-law, because I started with nothing.”

It only went up from there. Two years later they got their own apartment and by 1952 Couturier was again taking engineering courses. “Wherever I went I was studying my books: In the subways, going to work, on the beach on weekends. I graduated in ‘56, in four years.”

Robert Couturier. Photo

Couturier would work for other companies and often there was extensive traveling involved, which he seems to have enjoyed (much of this is recounted on his blog). He was in on the ground floor of General Datacom as their chief engineer. “We made all sorts of communication equipment for private networks because the internet didn’t yet exist.”

“We lived in Stamford, Connecticut, on the East Coast for 57 years,” he says. “The reason we came here was because all my kids came to the L.A. area.” Besides, in their hometown, their friends and relatives had “disappeared, one after another. Pretty soon we didn’t know anybody in the street. So we bought this place. For a while we were doing six months here, six months over there. I finally sold the house and we moved here.”

If not to sell it, why show it?

Despite deflecting any claim to being an artist, or to knowing what constitutes a legitimate artist, some years ago Couturier created a series of clever works from found objects in nature, mostly polished stones, twigs, or segments of branches that had, in many cases, been transformed by wind or waves. “I already had an eye for things,” he says.

“Fright,” by Robert Couturier: “A stylish depiction of a mass of birds that was quietly resting and then violently scared away. The disarray of their flight accentuates their surprise.”

And so now what about his 3D collages and assemblages?

“I’m not going to sell it,” Couturier replies, “because people will laugh at me. But, here comes the multiple sclerosis thing…”

A while ago he’d met the painter and muralist Lydia Emily, who has the affliction herself, and she became the inspiration and impetus for the event this Saturday and Sunday from 1 to 5 p.m. both days. It’s taking place in the rather elaborate clubhouse of the building where Couturier lives.

To circumvent the notion that he’s created his work for personal, financial gain, Couturier is presenting the two afternoon as a fundraiser with the entire proceeds going to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. “I don’t take anything, even the money I spent doing what I’m doing.” The individual pieces do not carry a price tag, but with a starting bid can be acquired through a silent auction.

Although his gallery-owning son and his granddaughter, Maya Grunauer (to whom the little exhibition is dedicated), have put the word out, “I don’t know how many people will come and see it, because this is a private place,” Couturier says. That means we can’t just walk in off the street, but those with an express interest in attending can contact Robert Couturier and he’ll share the details. (310) 791-0723 or email cootrobert@hotmail.com. ER